Graham Reid | | 9 min read

Even today the jury is out on the album but nine years after Reed's death and almost half a century on from the album's release, what Myers had to say still stands. We publish it here with permission.

At the end we have a YouTube clip of the album if you haven't heard it. Play it while you read.

(If you are reading this on a phone the essay continues after the breakout quotes)

.

In the past few decades, Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music has been scrupulously analyzed by scores of pop-culture vultures who have delighted in picking apart what may be the most infamous rock ‘n’ roll swindle of all time. Almost everything seems to have been already said about Metal Machine Music. From serious analyses to not-so-serious prose, the facts, myths, quotes, lies, half-truths, accusations and discussions devoted to this radical piece of work have amounted to a huge pile of rubbish.

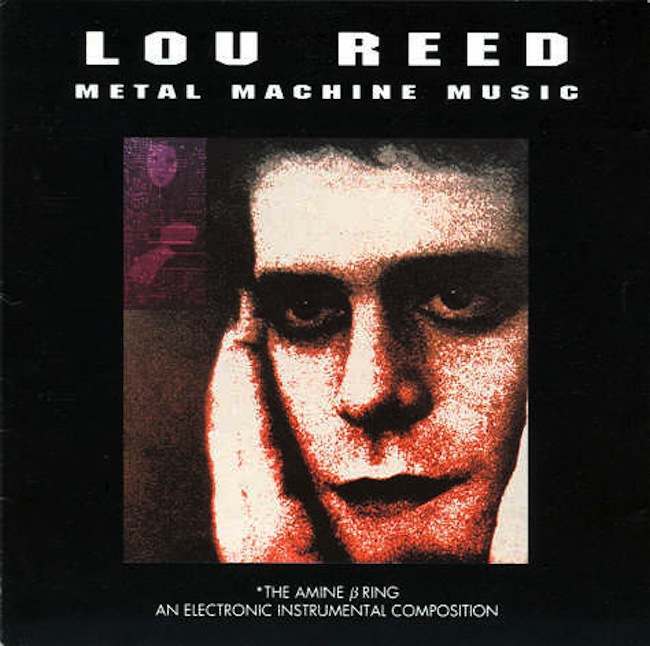

Consider these disparate bits: 1975’s Metal Machine Music was Reed’s seventh solo release after leaving the Velvet Underground. It was also his first double LP, which affirmed RCA Records’ faith in the marketability of its most notorious recording artist.

Recorded in Reed’s Long Island studio near Pilgrim State Hospital, his magnum opus was formed without conventional instrumentation. Rather than using standard musical instruments or the human voice, Reed chose to stack multiple combinations of reverberating electronic sound, creating a vast, industrial howl.

Recorded in Reed’s Long Island studio near Pilgrim State Hospital, his magnum opus was formed without conventional instrumentation. Rather than using standard musical instruments or the human voice, Reed chose to stack multiple combinations of reverberating electronic sound, creating a vast, industrial howl.

Derived from a process of manipulating aural frequencies and distorting both the intensity and pitch, Reed’s mechanized drones and harmonic buildups released shifting waves of pulsing white noise and emitted squeals of pure feedback into two separate, but equal, stereo channels.

On the album’s back cover—above an incorrect chemical diagram of an amphetamine concoction—a specifications list included such things as ring modulators, tremolo units, high-filter microphones and Jimi Hendrix’s Arbitor distortion box. “No Synthesizers No Arp No Instruments?” the list concluded, “No Panning No Phasing No.”

In many ways, that last, lone “No” betrayed the true underpinning of Metal Machine Music’s original concept.

Representing a diametric shift away from his then-popular musical identity as the androgynous rock ‘n’ roll poet laureate of Manhattan’s mean streets, Reed’s oppositional soundscape couldn’t have been anticipated, even as an extension of the feedback/noise/distortion found within groundbreaking Velvet Underground songs like Sister Ray.

This new music, Reed contended, was “the perfect soundtrack to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” He also claimed to have inserted tiny snippets of classical music into the mix and that many of the frequencies were dangerous, and even illegal, to put on a record.

While today’s generation of ambient/environmental/electro-acoustic drone mavens were still learning to crawl, Reed had already employed the studio as an instrument, resulting in an imposing soundtrack of electronic doom.

In interviews, Reed compared his unusual effort to those by avant-garde composers La Monte Young (whose name he misspelled on the back cover) and Iannis Xenakis.

In interviews, Reed compared his unusual effort to those by avant-garde composers La Monte Young (whose name he misspelled on the back cover) and Iannis Xenakis.

Although his VU bandmate John Cale worked extensively with Young and Tony Conrad in their Dream Syndicate prior to and during his involvement in the Velvet Underground, Reed never really associated with the heady bunch of Manhattan drone-art-conceptualists during the Syndicate’s speed-inspired marathons of minimal music making.

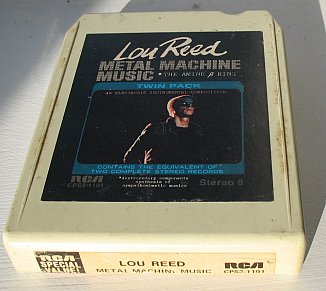

Still, Reed claimed he had been working on Metal Machine Music for six years and began discussing the esoteric sound maze in several major music magazines. While this was a huge artistic gamble for Reed, RCA backed him to the hilt by issuing the recording on both stereo and quadraphonic vinyl as well as eight-track tape.

Of course, none of these efforts prevented the release from becoming a complete commercial disaster.

While Metal Machine Music was reputed to have initially sold 100,000 copies, it was also reportedly the most returned album in RCA’s history. In a frantic effort at damage control, RCA pulled Metal Machine Music from store shelves and rerouted it straight into the cutout bins.

While Metal Machine Music was reputed to have initially sold 100,000 copies, it was also reportedly the most returned album in RCA’s history. In a frantic effort at damage control, RCA pulled Metal Machine Music from store shelves and rerouted it straight into the cutout bins.

Looking to stem additional loss, RCA canceled the album’s release in England altogether. Since then, Metal Machine Music (subtitled An Electronic Instrumental Composition: The Amine ß Ring) has become one of the most sought after eight-tracks of all time, right up there with vintage sound oddities like Yoko Ono’s Fly.

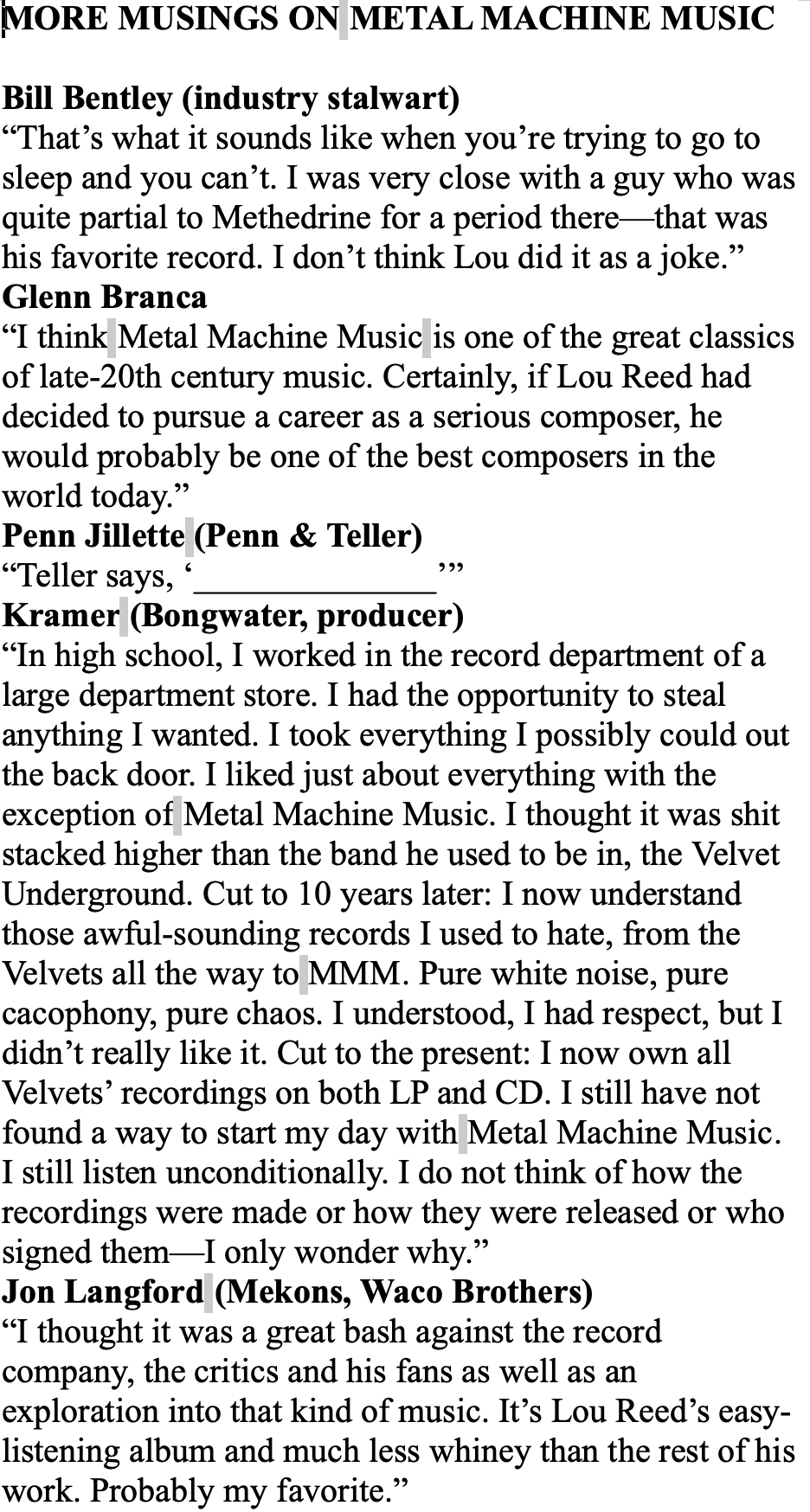

It shouldn’t be forgotten that late rock critic Lester Bangs waxed poetically, prolifically and prophetically on MMM.

In his classic Creem article “The Greatest Album Ever Made” (later immortalized in posthumous collection Psychotic Reactions And Carburetor Dung), Bangs provided 17 lively reasons why MMM was superior to his second choice, Kiss’ Alive!.

Bangs and Reed jousted brutally when discussing MMM, most of which was dramatically documented in another brilliant essay, How To Succeed In Torture Without Really Trying.

Yet Rolling Stone voted MMM the worst album of the year. Billboard said simply, “Recommended Cuts: None.” MMM was totally panned by most critics, although Robert Christgau was merciful in his Consumer Guide, giving it an almost-respectable C+ grade.

Yet Rolling Stone voted MMM the worst album of the year. Billboard said simply, “Recommended Cuts: None.” MMM was totally panned by most critics, although Robert Christgau was merciful in his Consumer Guide, giving it an almost-respectable C+ grade.

In The Trouser Press Record Guide, Ira Robbins described “the truly deviant Metal Machine Music” as “four sides of unlistenable noise (a description, not a value judgment) that angered and disappointed all but the most devout Reed fans.”

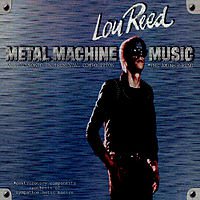

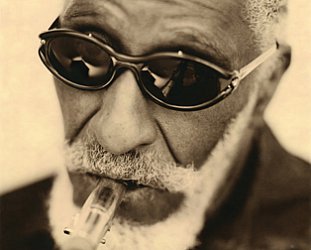

Often characterized as a scam that simultaneously enacted revenge on Reed’s manager, fulfilled a commitment for product to RCA and eliminated a growing congregation of less-than-sophisticated admirers, MMM was guilty of deceptive packaging. The album cover featured a leather-clad Reed wearing sunglasses, hair peroxide blond and looking every bit the decadent glamhead.

Indeed, this image was similar to the punk icon who first captured the imagination of America’s record-buying youth with Walk On The Wild Side and then went in for the kill via the twin-guitar pyrotechnics of live album Rock ‘N’ Roll Animal.

Imagine teenagers all over the country rushing home with their brand-new Lou Reed album, only to conclude that something had gone terribly wrong with their stereo systems or, worse yet, Reed had ripped them off with a bunch of irreverent noise.

Imagine teenagers all over the country rushing home with their brand-new Lou Reed album, only to conclude that something had gone terribly wrong with their stereo systems or, worse yet, Reed had ripped them off with a bunch of irreverent noise.

John Holmstrom, the former editor of Punk who interviewed Reed for the visionary fanzine’s first issue in 1976, described the album’s monumental impact this way: “Metal Machine Music is one of the greatest records of all time. It kicked off the whole punk movement. I mean, it nearly destroyed Lou’s entire career. How much more punk can you get than that?”

So, Metal Machine Music: a grand punk statement, an electronic composition of indecipherable depth or both?

Whatever the case, it was one of the most controversial pop-music products of the 20th century. But when looking at the album as art, you’re also inclined to contemplate the artist.

Prior to the release of MMM, Reed had gone through a divorce, was in a state of near exhaustion, was cohabiting with a drag queen and had been hit in the face with a brick while performing in Europe. Reed also created the album during a period in his life when he was heavy into doing drugs, especially shooting speed.

With references to amphetamines, pharmaceutical handbooks and apocryphal comments like “those for whom the needle is no more than a toothbrush” littering his bitterly rambling album notes, Reed flagrantly trashed the boundaries of both professional and personal decorum.

With references to amphetamines, pharmaceutical handbooks and apocryphal comments like “those for whom the needle is no more than a toothbrush” littering his bitterly rambling album notes, Reed flagrantly trashed the boundaries of both professional and personal decorum.

Rumored, and then denied, to have been a candidate for release on RCA’s classical-music imprint Red Seal, Metal Machine Music was immediately and forever stuck between rock music and a hard place. There were even faint apologies made by the artist for not having a proper disclaimer on the cover, which were angrily rescinded the next time he spoke to the press.

With Reed’s uncompromising electronic maelstrom spread across four sides of vinyl and each untitled side listed as exactly 16:01 in length (this, too, proved to be untrue), Metal Machine Music was unlike any other record ever released by a “rock” personality.

While the record itself has been long out of print, Metal Machine Music somehow managed to find new life on CD in Germany and the U.K. Like the celebrated eight-track format, a compact disc allows you to hear Reed’s sonic montage from beginning to end, all without making consecutive decisions to forge ahead with sides two, three and four.

When I began this investigation, I encountered one unanticipated snag that brought my research to a virtual standstill: I kept listening to Metal Machine Music. The more I heard it, the more I liked it, and this concerned me greatly. My desire to hear conventional music diminished, and my friends all stopped visiting

I was feeling down about the whole thing until I bumped into Steve Albini at the Empty Bottle club in Chicago. After explaining my obsession with MMM to him, Albini kindly consented to discuss the record.

I was feeling down about the whole thing until I bumped into Steve Albini at the Empty Bottle club in Chicago. After explaining my obsession with MMM to him, Albini kindly consented to discuss the record.

“When I lived in Montana in 1977, a friend of mine told me about this weird Lou Reed album that everybody hated but he thought was pretty cool,” says Albini.

“He played it for me, and I thought it was just totally captivating, really amazing. The thing that we both appreciated about it was that within the noise, there are these little fluttery beautiful tiny melodic bits, which are probably part of the generative systems that were put together to make all the sounds. Those sounds may not have been orchestrated or intentional in any way, but were there and no less interesting.

“People refer to that record as though it were completely chaotic noise. I have a lot of records that are completely chaotic noise, and that is a total misunderstanding of this record.

“Whatever Lou Reed’s motive for making it, it’s still a really outstanding non-harmonic piece of music. There were clearly choices made about how much density and which sounds in particular would get layered on top of each other. I don’t hear Metal Machine Music as a feedback-and-improv record; I hear it as a pure sound sculpture. I really enjoy listening to it. It’s not that weird. It’s only weird given that it came out in 1975 and was presented as a pop-music record.”

This is exactly what I was looking for.

Someone articulate and knowledgeable who thinks Metal Machine Music is cool and fun to listen to. Perhaps Bangs did know what he was talking about when it came to Metal Machine Music. Reed himself said, “In time, it will prove itself.” Reed also said he laughed himself silly after presenting it as a serious piece of music to the honchos at RCA.

I really don’t know what to believe, but I do know a good controversy when I hear one.

Play it again, Sam.

.

Mitch Myers is a freewheeling American rock writer, historian, psychologist and music critic whose book The Boy Who Cried Freebird was a wonderful mix of fact, fiction and fables about rock'n'roll culture, fans and fantasies.

Mitch Myers is a freewheeling American rock writer, historian, psychologist and music critic whose book The Boy Who Cried Freebird was a wonderful mix of fact, fiction and fables about rock'n'roll culture, fans and fantasies.

Elsewhere recommends it highly.

Myers contributes to Magnet magazine in the US (see here), is a regular on National Public Radio and has been the curator of the Shel Siverstein Archive in Chicago, the songwriter, cartoonist, children's book author, playwrite, Grammy winner . . .

.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging

Graham Dunster - Nov 29, 2022

Don't forget Metal Machine Trio, the Lou Reed double cd recorded in LA in 2008... I haven't played it in a while though - so much choice, so little time! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metal_Machine_Trio

Savepost a comment