Graham Reid | | 2 min read

Sergej Bezrodny and Vladimir Spiakov: Spiegel Im Spiegel

Some of the best pop music ever written sprang from the need to sing about the forbidden, particularly by dipping into that well-spring of denied human desire.

In western culture, forbidden desire yielded pop classics such as Cyndi Lauper’s She Bop and Turning Japanese by the Vapours, songs that topped the pops despite their implied rude lyrical content.

Behind the Iron Curtain in the east, to offend social sensibility was to sing about Christianity, which is, as any halfwit Marxist can tell you, the opiate of the masses and therefore heretical.

To play music about God in the United Soviet Socialist Republic was just like singing about masturbation and orgasm on Ready to Roll on a week night in suburban New Zealand. Except there were no pops to top in early 1980s Moscow.

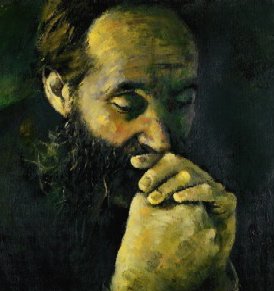

But if there had been, and there truly was a God, then surely devout Estonian composer Arvo Part would have been rocking them in Riga and slaying them in St Petersburg. But when he tried it on with a piece called Credo, it was banned and authorities slapped restrictions on performance of his music.

If Part was to succeed, he would have to hide his God in instrumental music, let the violin and piano speak his faith, even if only he could hear the inspiration.

Artists often transcend the limits of their craft when they attempt to subvert formal conventions, while still appearing to conform. For instance, Lauper creates a great pop ditty by incorporating the theme of female self-pleasure into the radio friendly hit, She Bop; Chuck Berry in My Ding-a-ling however fails to create anything memorable by tackling a similar subject head-on.

I never cared for Part’s Credo (too bombastic in its message-making and music) but his spare, understated composition Spiegel im Spiegel is a remarkable tune. In that sense, the communists did music lovers a favour by forcing him to speak of his religion through a simple piece for piano and violin.

It was written in 1978, a time when punk was first emerging to turn pop music on its head, and was Part’s last composition penned from behind the Iron Curtain before he and his wife fled Estonia, eventually settling in west Berlin.

Part, notoriously publicity-shy and reticent about the inner workings of his craft, has stayed silent on whether Spiegel is an overtly religious piece but it is too tempting not to speculate that this is the sound of blind faith.

Part certainly creates a strong sense of reverence in Spiegel, with its simple ascending arpeggio on piano, occasionally grounded with a bass chord, as if he were going toward the light. Over the top of this sparse setting, the violin sketches the most achingly sonorous melody that yearns for a perfection that can never be.

Violinist Daniel Hope, in his version, plays these notes with a barely-drawn bow, so that the sound is rendered with even more sympathy for the hopeless human condition, for surely that is Part’s intention with this tune.

As the title, Mirror in the mirror, indicates, this melodic phrase somehow repeats yet subtly changes, seemingly about to disappear off into to some aural vanishing point but then returns to beguile again. It manages the emotional trick of being both unsettling and deeply comforting. Spiegel’s charm lingers long after the last note has faded.

Part also wrote alternative pieces, with cello and viola taking the violin’s part but for my money, the violin piece is the first and best.

CD: Alina, Arvo Part

POP EQUIVALENT: Before and After Science by Brian Eno (see here)

For more on Arvo Part go here.

Nick Smith is an Auckland writer and a musician who recorded for the short-lived Real Groovy Records label in the Eighties. You can hear one of his songs pulled From the Vaults here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging, huh?

post a comment