Graham Reid | | 3 min read

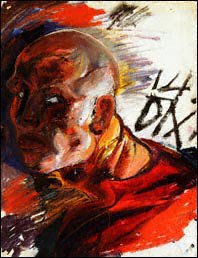

The paintings of Otto Dix are as unrelentingly abrasive as a mincing machine. It’s the kind of art you get when society is forced through a sieve then put under a microscope. It’s impossible to not be confronted by his work.

In the documentary Ten Times Dix (Arts Channel, Thursday April 12, 8.30pm), we’re introduced to Otto by way of a short clip from an interview in 1966, two years before his death. Self-conscious in front of the camera, he says he can’t imagine anyone being interested in a film about him, except perhaps in 50 or 100 years.

In 2012, he’s proven right.

Ten Times Dix is structured around the staging of a major exhibition of the artist’s vast body of work at the Montreal Museum of the Arts titled ‘Cabaret’.

Hoisted above the museum’s façade, a massive banner depicting a woman sprawled on a leopard’s skin suggests an exhibition about the Weimar of the 1920s-30s, but her short-cropped hair, make-up and fleshy pose are wholly attuned to the 21st Century world of Lady Gaga.

Rather than images of Weimar glam, the show depicts a vision of living hell.

Dozens of prints and paintings not only reveal the terror and butchery of war (in which the reality of the trenches is made viscerally palpable), but something disquietingly frank about mankind’s appetite (perhaps even lust) for violence and carnage.

The nightmare of the First World War was not wasted on Dix.

He kept a diary and carried sketchbooks to document much of what later turned into prints and paintings, and he openly admitted to an attraction to the thrill of killing offered by war. Such honesty is almost too difficult to comprehend, but perhaps the dark side of our nature must be confronted if we wish to be wholly alive and compassionate human beings, even more so for those who choose to be artists.

The art of Otto Dix allows us that opportunity, but with none of the facile posturing of carved up cows and floating sharks.

Surviving the war (with a near fatal neck wound in 1918) gave Dix a fearlessness that he channelled directly into his work. Having faced death and survived, he expressed himself without constraint.

Dix and his contemporaries (Max Beckmann, George Grosz, El Lissitzky) plied their provocative craft within a receptive culture, and it was during this post-war period (the Weimar Republic of the Twenties and Thirties) that he found his artistic rhythm.

This is where the ‘cabaret’ comes in, but it’s hardly show time, more like a danse macabre.

With explicit portrayals of sexual murder (echoes of Sickert’s Camden paintings) and brothel visitations, Dix’s unflinching focus makes for uncomfortable viewing. Honing his skill on a culture in decline, he found beauty where others could only see ugliness.

When the Nazis came to power, he was blacklisted as a degenerate and almost 300 works were confiscated. For most artists, this would amount to the loss of a lifetime’s work, which many would struggle to overcome. Interestingly, rather than destroy these unsavoury paintings, the Nazis auctioned them off in dubiously neutral Zurich.

It infuriated Dix at the time, but ironically this corrupt twist of fate is the reason why much of his earlier work still exists.

Given the Nazi propensity for destroying “deviant” art, it amazes me so much of Dix’s work survived.

Seven Deadly Sins of 1933 is an extremely potent work, critical not only of the Nazis but Hitler in particular.

A tormented infant sporting Hitler’s moustache sits on the knee of an old crone, death waving a sabre above his head. There’s no mistaking the point being made.

More remarkably, in 1939 Dix was

detained for being complicit in a plot to kill Hitler.

More remarkably, in 1939 Dix was

detained for being complicit in a plot to kill Hitler.

He survived this situation while others were carted away and locked up (or worse) for simply breathing.

And yet in 1942 this supposed artistic miscreant was commissioned by von Ribbentrop to paint his portrait.

Dix refused.

We’ll never know what Hitler thought.

Otto Dix never bowed to flattery or allowed his work to turn visually fat, vain, sentimental or repetitive.

The profoundly disturbing truth reflected in his work is that human nature remains fundamentally unchanged regardless of the terror and anguish of the past.

The Nazis claimed that Dix’s work “threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves”.

If only.

Viky Garden is an Auckland artist whose work can be viewed here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging, huh?

post a comment