Graham Reid | | 3 min read

The history of music is the history of revolution.

Sometimes the change is technological – the invention of the piano caused a massive upheaval in the way people wrote and played music and it changed the sensibilities of the 18th and 19th Century listening public.

Similarly, the electric guitar and amp became the musical equivalent of the AK47 as rock’n’roll revolutionaries took the fight to the establishment. They fought the law and, for a change, the law lost.

Sometimes revolution is simply social and artistic without technological innovation. It is hard to believe there were riots when Stravinsky unveiled The Rite of Spring in 1913. He changed classical music but the piece sounds tame now. But so too does the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks, which also antagonised and thrilled audiences in equal measure 65 years later.

Other times the revolution is a quiet subversion from within, so that the full impact of the mutiny is not apparent for many years.

Such a musical coup d’etat has been occurring in classical music for the past two decades. And, weirdly, it is the conservatives, the people who look back over their shoulder to see the way things should be done, who are changing music for the better.

The drive to present an “authentic” experience saw musicians taking up the original instruments used when the song was first written. So, instead of the full, rich tone of the modern cello, you’d get the more woody, reedy sound of the violincello; the monochrome of the harpsichord instead of the piano’s tonal kaleidoscope. It’s fair to say reaction to this change was mixed.

But when musicians turned their attention to the way old music was presented back in the day, the desire for authenticity proved an utter triumph and changed classical vocal music, in particular, in a fundamental way.

For instance, in Bach’s time there was no massive choir and full orchestra. He was a successful composer but with limited resources and he wrote his songs with what was available at the time – a small singing ensemble and chamber orchestra.

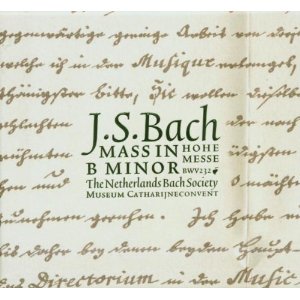

Yet until recently Bach’s great pieces like the Mass in B Minor were performed with a small army of singers and an orchestra featuring more bells and whistles than at a Morris dancers’ Jamboree.

This resulted in many of the best songs being lost in the muddle of massed voices and instrumentation. Even classical superstars such as Sir Neville Marriner, who recorded a terrific version with Janet Baker and Robert Tear, among others, over-egged their Bach omelette.

In 2006, the Netherlands Bach Society,

featuring a bunch of relative nobodies, staged the B Minor Mass with

only a 21-strong orchestra, five soloists and a choir of just nine

singers (the soloists pitch in when not required for main singing

duties).

In 2006, the Netherlands Bach Society,

featuring a bunch of relative nobodies, staged the B Minor Mass with

only a 21-strong orchestra, five soloists and a choir of just nine

singers (the soloists pitch in when not required for main singing

duties).

It certainly beggars belief they staged it with just five fiddles, one viola, one cello and a double bass.

The result from such drastic downsizing in personnel is a complete reinvention of Bach’s masterpiece; it truly sounds as if made anew. The big chorus numbers like opening track Kyrie eleison manage the neat trick of sounding intimate yet still larger-than-life. For the first time you can actually hear the words being sung rather than massed blocks of notes.

But it is when all the soloists pitch in together on tunes like Et incarnates est and Crucifixus that this version is elevated into the music of the Gods. The singing is delicate, perfectly poised and achieves a symmetry that is simultaneously sober and uplifting.

The singing is somehow different from the way classical singers used to do it last century; it is more natural and easier on the ear and this can be directly attributed to the “authenticity” movement.

A good comparison can be found in pop music, which in the Fourties and Fifties was dominated by this romantic style of singing featuring a heavy vibrato (classical was also infected; listen to violinists Fritz Kreisler or Yehudi Menuhin and cringe).

But this gave way to a more naturalistic, less mannered style of singing and that’s what the authenticisists have achieved with classical.

It’s not just my opinion; I’ve interviewed classical singers, who, when quizzed about this revolution, are adamant that singing styles have changed.

If I was to cite one piece to convince pop fans that classical music will rock their world, it would by the Netherlands Bach Society’s Mass in B Minor. It is a masterpiece, chock full of great tunes.

Viva la revolution.

POP EQUIVALENT: Like one of those rare

classic rock albums where nearly every single song is a gem. For me

that would be Radiohead’s The Bends

Nick Smith is an Auckland writer and a musician who recorded for the short-lived Real Groovy Records label in the Eighties. You can hear one of his songs pulled From the Vaults here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging, huh?

post a comment