Jonathan Ganley | | 4 min read

“I have often thought that if photography were difficult in the true sense of the term – meaning that the creation of a simple photograph would entail as much time and effort as the production of a good watercolour or etching – there would be a vast improvement in total output. The sheer ease with which we can produce a superficial image often leads to creative disaster …”

-- Ansel Adams, from 'A Personal Credo', 1943.

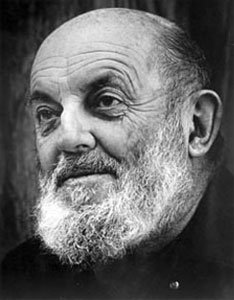

I sat down to watch Ansel Adams; A Documentary Film (Sky Arts Channel, Thursday April 4, 8.30pm) eager to learn more about the life and work of the great American photographer Ansel Easton Adams (1902-1984).

The documentary did not disappoint as it gives a comprehensive overview of the man and his times, and reveals a lot about his motivation and drive to create such powerful landscapes of Yosemite and the wider American West.

It seems to me that viewing Adams’ work is a two edged sword for anyone who takes their own photographs and also enjoys and absorbs the work of others.

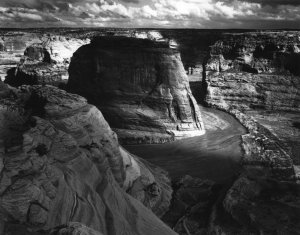

When I look at a photograph such as

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941, right), I wonder why I even try.

When I look at a photograph such as

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941, right), I wonder why I even try.

It seems certain that no one will be blessed again with that combination of a perceptive eye, skill, technique, opportunity and tenacity. Adams’ commitment to his craft now seems part of another time.

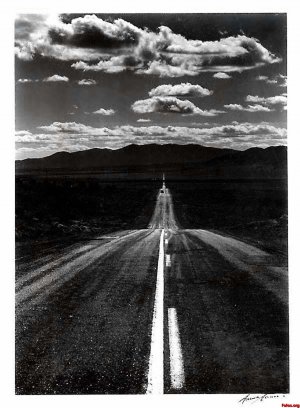

We live in a digital age, and we take that ‘sheer ease’ for granted. Our telephones have built-in cameras with phenomenal image clarity. Digital still cameras capture enormously detailed images and can also shoot high-resolution video. Decisions about exposure can be left to automation and the results are nearly always acceptable.

I thought about Adams’ legacy and it seemed sad to me that his definitive books The Negative and The Print, containing the accumulated photographic processing knowledge of his long lifetime, may have become curiosities in this era of digital photography. This raised another question in my mind. What can Ansel Adams’ photographic legacy offer us in the age of Instagram?

For anyone who cares to seek out Adams’ knowledge, there is still so much to be learned from the master.

The photographer is literally ‘painting with light’, no matter what device is used to capture the image, and the same principles that Adams applied to his photography are still relevant today. Adams' method of pre-visualisation was to envisage in his mind exactly how the image would appear on the final print, and adjust his exposure and the subsequent development and printing accordingly.

A photographer can also apply pre-visualisation to their digital images.

If the camera has some manual control over the exposure, then the overall effect and range of tones in the final image may be achieved more easily. The controls in applications such as Photoshop and Lightroom can then be used to enhance the image and gain the same kind of creative control that Adams achieved through careful exposure, development and printing.

The key to understanding Adams’ approach to the process of photography is that he was always methodical in everything he did.

However, the documentary examines several key moments in his life that seem to have had an almost spiritual impact, and were crucial to his understanding of the potential of photography. The first occurred in 1923 when Adams was climbing in Yosemite and became acutely and overwhelmingly aware of his perception of light, and felt he saw more clearly in those moments than he ever had before, or would again. These “arrows of light through the glassy air” were a transcendental moment of life-affirming certainty for Adams.

Four

years later, during another climbing expedition, Adams decided to try

to convey the drama and majesty of a mountain scene by using the deep

red filter on his final exposure of the day, which had the effect of

dramatically darkening the sky and deepening the shadows in the black

and white image. He felt the resulting print had at last conveyed how

the mountain scene felt to the photographer, and therefore could

convey that feeling to the viewer.

Four

years later, during another climbing expedition, Adams decided to try

to convey the drama and majesty of a mountain scene by using the deep

red filter on his final exposure of the day, which had the effect of

dramatically darkening the sky and deepening the shadows in the black

and white image. He felt the resulting print had at last conveyed how

the mountain scene felt to the photographer, and therefore could

convey that feeling to the viewer.

It was not long after this that Adams wrote to his wife Virginia that he felt at last his photographs were worthy of the world’s attention. Incidentally, when the documentary examines Adams’ personal life, a picture emerges of a complex and contradictory man.

He was perhaps more in love with the landscape and beauty of Yosemite than he was with Virginia, whom he met there and married after an on-again/off-again courtship of many years.

For me, it was

fascinating when the documentary stepped past these defining moments

in Adams life and we see him working in the darkroom, demonstrating

the arcane skills of dodging and burning the exposure of the negative

onto photographic paper, increasing or decreasing the print contrast

and fulfilling his pre-visualisation of the image.

For me, it was

fascinating when the documentary stepped past these defining moments

in Adams life and we see him working in the darkroom, demonstrating

the arcane skills of dodging and burning the exposure of the negative

onto photographic paper, increasing or decreasing the print contrast

and fulfilling his pre-visualisation of the image.

Adams once famously observed that the negative was the musical score and the print was the performance

It was astonishing to see this performance in action, and to witness his physical involvement with the process - his fingers delicately lifting the paper from one bath to another, and his hands immersed and agitating the harsh alkaline developer over the paper as it lay in the tray.

These scenes in the documentary are fleeting, but they convey an impression of a man who was at ease with the processes, his skills honed with countless hours of practice.

I realised that ultimately it doesn’t matter if you have the latest DSLR and use Lightroom, or load up the 35mm camera with a roll of Kodak Tri-X.

Ansel Adams’ principles of methodical photography, of correct exposure, of pre-visualisation and perfect workmanship will always hold true.

Jonathan Ganley is an Auckland photographer whose work has covered many subjects, notably however New Zealand musicians. Some of those portraits appeared previously at Other Voices Other Rooms here, and a gallery of his work is available at his website pointthatthing.com

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words or fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment