Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Imagine: you’re at a party, and you’re talking about whatever it is you like to talk about at parties – your children, probably, or how you don’t understand music or fashion or politics any more. . . And then some lanky unshaven lummox approaches your little circle and tells you that when Scott arrived at the South Pole 101 years ago, he already knew the race was lost.

The first sign had come in Sydney nearly two years earlier, this stranger says, when a terse telegram arrived from Amundsen, the renowned Norwegian adventurer: "Beg to inform you Fram proceeding Antarctic" – a laconic, gentlemanly challenge, putting the British team on notice that game was afoot.

A year passed with no contact between the two expeditions, until in the summer of 1911 the Terra Nova steamed into the Bay of Whales on the Great Ice Barrier, and against all probability encountered the Fram, the only other ship for thousands of miles in any direction.

The news reached Scott at his base on Ross Island, and he expressed his distress in his diary, elegantly as always: "The proper, as well as the wiser, course for us is to proceed exactly as though this had not happened. To go forward and do our best for the honour of the country without fear or panic."

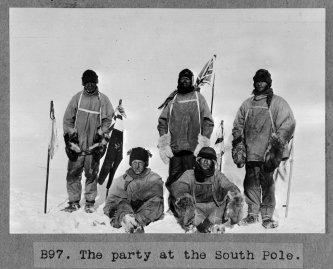

In the days before their arrival at the pole, the British team had seen disquieting signs of Amundsen’s party – route markers and cairns, and finally a black flag on the horizon, which as the men struggled nearer proved to be flying over a Norwegian tent, pitched as nearly as they could determine on the South Geographic Pole.

They had been beaten.

Inside the tent, a polite

note addressed to Scott himself begged the Englishmen to carry a

letter home to King Haakon of Norway, so the Norwegian claim could be

verified in the likely event of the death of Amundsen’s party on

the return journey.

Inside the tent, a polite

note addressed to Scott himself begged the Englishmen to carry a

letter home to King Haakon of Norway, so the Norwegian claim could be

verified in the likely event of the death of Amundsen’s party on

the return journey.

"Great God!" wrote Scott, shivering in his sleeping bag that night, "This is an awful place, and terrible enough to have laboured to it without the reward of priority… now for the run home, and a desperate struggle. I wonder if we can do it?"

As it turned out, they couldn’t, dying one by one on the return march in the desperate cold -- but by God they did their best.

What rotten luck! What hubris! What a colossal, ambitious, brutal and beautiful train wreck.

The mind boggles, the eye is drawn, the limbs begin to shiver and we can’t look away. The five men plod homeward, dragging a punishing load and falling one by along the way to lie unmarked but not forgotten, until the last tent is pitched in a blizzard and three men die side by side only 11 miles short of salvation.

And we can read about it, of course, and we can obsess about the details – why ponies? Why ponies, but no showshoes for the ponies? Why didn’t Bowers have skis? Why did the paraffin run out? -- or we can remember that sometimes when you go out, even if you do your best, you don’t come back.

What Scott left behind, as well as an entire apparatus and method of scientific polar exploration, an expedition so meticulously organised and planned that the surviving members were actually able to trace his footsteps the following summer and, in the middle of all that howling, untracked emptiness find his body.

As well as all that, Scott left us one of the most

remarkable works of autobiography from anywhere ever: his diary.

Writing conscientiously to the last, freezing and starving in his tent, he speaks to us in eloquent and literate Edwardian prose, reporting on everything from geology to the deaths of his companions in the same style: mannered to the end, reserved but engaged, and always desperately concerned for the welfare of his people.

He also, in his decision to hire Herbert Ponting as the first professional photographer to accompany

an Antarctica expedition, left us a treasure trove of iconic images, including Scott's last birthday supper (right).

He also, in his decision to hire Herbert Ponting as the first professional photographer to accompany

an Antarctica expedition, left us a treasure trove of iconic images, including Scott's last birthday supper (right).

Ponting taught Scott the art and science of photography and it is a testament to Scott’s intelligence and adaptability that he was able to master the cumbersome glass-plate apparatus with all its complex filters and lenses in an environment so cold that even touching a brass fitting meant losing a layer of skin.

Some of the most memorable photographs were produced by Scott himself – the ponies waiting stoically in the snow, a sledging party struggling up the Beardmore Glacier, that heartbreaking shot of the Norwegian tent at the pole (below right).

I came upon these photos, and Scott’s

diary, in a brightly-lit, air-conditioned library – neatly filed

away down the very end of the Dewey Decimal system.

I came upon these photos, and Scott’s

diary, in a brightly-lit, air-conditioned library – neatly filed

away down the very end of the Dewey Decimal system.

As soon as I’d seen them I couldn’t get them out of my head, and I lost sleep reading the diary, gazing at the photographs and hunting around for more – letters, books, contemporary writing, later criticism, and modern reappraisals.

I was hooked, of course, a starry-eyed enthusiast and overnight became that crashing bore at parties – interrupting completely unrelated conversations with half-remembered anecdotes and demanding that innocent bystanders listen to the stories and agree that yes, Captain Scott was quite an extraordinary chap, wasn’t he?

It was really very antisocial.

So this song Great God! This Is An

Awful Place posted as a video below -- and the album that it’s taken from -- are part of my

efforts to become a better dinner guest.

So this song Great God! This Is An

Awful Place posted as a video below -- and the album that it’s taken from -- are part of my

efforts to become a better dinner guest.

I figured that maybe if I got the whole thing out of my system, I might find something else to talk about and perhaps people would start inviting me to things again.

I took the diaries and the letters, and the poems that Scott and his men loved so much – Browning, Kipling, Tennyson, Robert “The Canadian Kipling” (Good Lord! Really?) Service – and I took the stories I’d gleaned from so many later works on the expeditions, and I sat down and I used all of this material to write some songs.

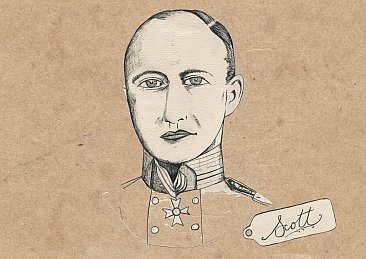

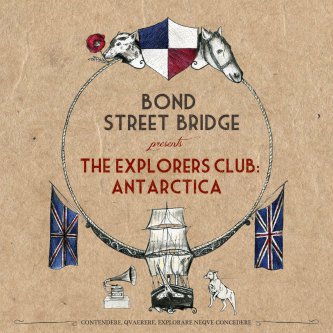

I asked the Alexander Turnbull Library if I could use some of the images they hold, and they said yes (the ones reproduced here), and I asked Emily Cater whether she’d like to use those images and other material to produce illustrations to bring the songs to life, and she said yes too. That is her illustration of Scott at the head of this page, and on the album cover (below).

I taught the songs to the band and we drove around the country a few times telling the stories, singing the songs and showing the pictures to all and sundry, from Bayly’s Beach to Invercargill and points in between, and then we went into the studio and made an album out of it.

After all that, you might think that I

would be sick of the whole thing, and maybe I could go back

delivering pithy one-liners about the state of the economy and

nodding sympathetically while people talk about their children.

After all that, you might think that I

would be sick of the whole thing, and maybe I could go back

delivering pithy one-liners about the state of the economy and

nodding sympathetically while people talk about their children.

You would not be alone in thinking that . . . but I regret to say that you would be wrong.

A year into this obsession and I am keeping the faith – the album (right) comes out next week, we’re hitting the road again for another string of shows (dates below) . . .

And I’m reading Scott’s diary, preparing myself for late-night barroom monologues and derailed dinner-table conversations from Auckland down to Milford Sound.

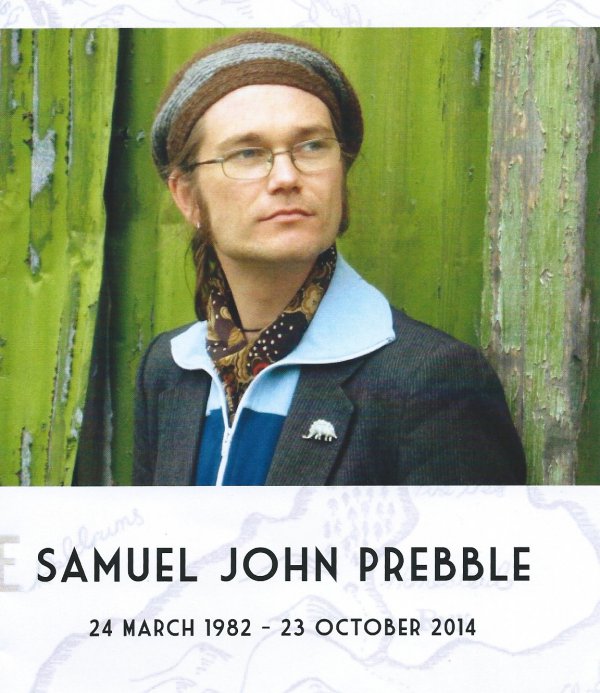

Sam Prebble is an Auckland singer-songwriter who records and performs with his band as Bond Street Bridge. He has also guested on albums by the likes of White Swan Black Swan, Reb Fountain and with the Broken Heartbreakers.

The new album The Explorers Club: Antarctica is out on Banished From the Universe Records. More information about the project and the tour are at www.bondstreetbridge.com. Photographs of Scott's expedition are reproduced here with permission from the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment