Jonathan Ganley | | 4 min read

Opening with a barrage of rapid-fire images of war, turmoil and protest, Chevolution is a documentary focusing on a single photograph. It examines how one image of a handsome revolutionary took on more significance and meaning than the photographer, or the subject, could have imagined.

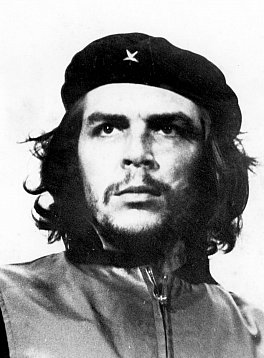

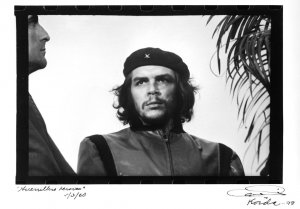

Alberto ‘Korda’ Díaz Gutiérrez was the Cuban photographer who shot many pictures of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, but is best known for one single 35mm black and white photo, cropped to portrait format and entitled ‘Guerrillero Heroico’. Instantly recognisable, this image may rightfully be called ‘iconic’, in a time when that word is routinely applied to everything from cars to smartphones, and has been bled of real meaning.

Chevolution -- which screens on the Sky Arts Channel, Saturday October 26, 8.30pm -- examines the events that brought Guevara and Korda together and the circumstances behind the photograph.

‘Guerrillero Heroico’ may possibly be the most reproduced image of the 20th Century, and shows no sign of losing any popularity today.

Yet the photograph itself was not staged or planned.

Watching this documentary reminded me that a

photographer, no matter how well prepared, equipped or technically

proficient, may still only succeed with a shot due to a combination

of good fortune and simply being in the right place at the right

time.

Watching this documentary reminded me that a

photographer, no matter how well prepared, equipped or technically

proficient, may still only succeed with a shot due to a combination

of good fortune and simply being in the right place at the right

time.

The exposure is often a tiny fraction of a second, but the events leading up to that moment may have taken place over many years, or even a lifetime.

Before 1959, Alberto Korda’s life had been one of photographer and playboy in the ‘fun loving, non-stop cabaret’ of pre-revolution Cuba. He was adjusting to a new life as a photographic propagandist for the revolution when, in March 1960, the camera-shy Comandante ‘Che’ Guevara stepped briefly onto a Havana stage with Castro and other leaders.

They were marking the deaths of 76 Cubans killed when two huge explosions ripped through the munitions ship La Coubre. The two images captured by Korda before Guevara slipped into the background again were not even printed immediately. Korda was in the right place at the right time, even if that realisation was not apparent until Guevara’s death.

The news of Guevara’s assassination in 1967, while fighting as an anonymous guerrilla for the National Liberation Army of Bolivia, was received with a mass outpouring of grief in Cuba. For Korda, the impact of his photograph became clear when he arrived at the public funeral in Havana and saw that ‘Guerrillero Heroico’ had been enlarged onto an enormous banner above the podium where Castro was to speak.

Watching this scene in the documentary I was reminded of the way that such huge images reinforce a cult of personality. The Communist party in China had already used enormous images of Chairman Mao on Tiananmen, and image banners of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin had all gazed at different times across Red Square in Moscow.

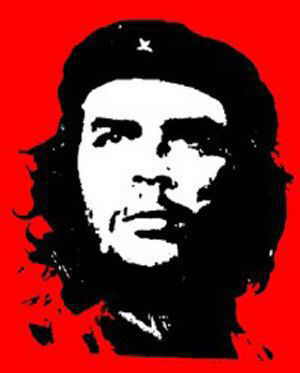

There is some speculation that ‘Guerrillero Heroico’ was already widely known in 1967 as it had already been used on a poster by the left wing Italian publisher Feltrinelli. What is certain is that the photograph was on placards during the May 1968 student protests in Paris and quickly spread across the world.

The image of the handsome

guerilla with the distant gaze seemed to encapsulate the

revolutionary ideals of the late 1960s.

The image of the handsome

guerilla with the distant gaze seemed to encapsulate the

revolutionary ideals of the late 1960s.

At this point I began to feel concerned for Korda’s copyright, which appeared to have been trampled at every turn.

However, the concept of copyright was considered bourgeois in post-revolution Cuba, and it wasn’t until the late 1990s that Korda was able to begin to enforce his copyright and protect the integrity of the image from misuse and from several unapproved corporate advertising campaigns.

The documentary then leads the viewer to consider what this image means today. Has it been stripped of all meaning now that it is so ubiquitous? And what do we really know about Ernesto Guevara? Is there more to his story than the cool guy in “The Motorcycle Diaries”, and that he looked good in khaki and wearing a black beret?

‘Che’ remains an idol but many of the young people interviewed in the documentary seem confused about his identity and background. One notable exception is the young Miami-based Cuban who questions how it can be that a photograph of a ‘dogmatic totalitarian Marxist’ now represents a ‘freedom loving, bohemian guy who questions authority’.

Chevolution is a compelling and frenetic jump cut through worldwide social history of the last 50 years and shows how a photographer can have a huge influence, not only in his own country, but across the world.

As one of Korda’s contemporaries points out, ‘the Cuban revolution would not have existed without photography’ but it seems almost as certain that ‘Che’ Guevara would not exist as an icon and idol without that one fleeting image captured by Alberto Korda.

Jonathan Ganley is an Auckland photographer and writer whose has frequently appeared at Other Voices Other Rooms (see here). His work has covered many subjects, notably New Zealand musicians. Some of those portraits appeared at Other Voices Other Rooms here, and a gallery of his work is available at his website pointthatthing.com All his photos are copyrighted, do not use without permission.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words or fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment