Graham Reid | | 1 min read

In 1967 Aretha Franklin went from the sophisticated studios of New York to a backwater in Alabama and finally had the hit that made her career: I Never Loved a Man.

Arriving at the studio, she was surprised to find her backing band was young white boys.

Looking back, and speaking with a royal “we” befitting the Queen of Soul, she said, “We didn’t know they’d be as funky – as greasy – as they were.”

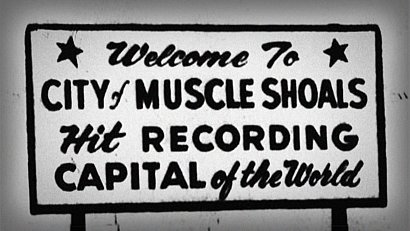

How Muscle Shoals (pop. 13,000) became one of the world’s leading recording centres is an extraordinary story. A farm service town in rural Alabama, it’s about as attractive as Huntly. But even that Waikato town has the advantage of being on State Highway One. (And, having produced the Topp Twins and Al Hunter, can claim its own genre: “Huntly and Western”.)

Muscle

Shoals is on the banks of the Tennessee River, about a two-and-a-half

hour drive southeast from Memphis. Before the mid-1960s, most

musicians drove to Memphis to try and make a living.

Muscle

Shoals is on the banks of the Tennessee River, about a two-and-a-half

hour drive southeast from Memphis. Before the mid-1960s, most

musicians drove to Memphis to try and make a living.

W C Handy and Sam Phillips were the two biggest music names to have emerged from the area, until 1961 when a black bellhop called Arthur Alexander recorded You Better Move On in a makeshift studio called Fame: Florence Alabama Music Enterprises. Percy Sledge’s heartbreaking When a Man Loves a Woman followed, then an association with Atlantic Records of New York, and the floodgates opened.

The music of Muscle Shoals is a triumph over adversity, racism, distance and tragedy. The tragic hero of the story is not the legendary band, or any of the visiting artists who recorded there.

It is Rick Hall,

the dirt-poor songwriter who founded the studio in the late 1950s.

Hall, a giant with a waxed moustache, is a driven character who has

received shocking setbacks that would break any human being. Yet he

managed to produce a catalogue of music that is sui generis -

of its own genre – the Muscle Shoals sound. (Even when his

musicians left to found their own studio, the sound survived.)

It is Rick Hall,

the dirt-poor songwriter who founded the studio in the late 1950s.

Hall, a giant with a waxed moustache, is a driven character who has

received shocking setbacks that would break any human being. Yet he

managed to produce a catalogue of music that is sui generis -

of its own genre – the Muscle Shoals sound. (Even when his

musicians left to found their own studio, the sound survived.)

Think of those electric piano chords played by Spooner Oldham that open Aretha’s I Never Loved a Man. The bump’n’grind beneath Wilson Pickett’s Mustang Sally. The erotic groove of the Staple Singers’ I’ll Take You There. The slinky rhythm of Paul Simon’s Kodachrome or the solid backbeat behind Dylan’s Slow Train Coming.

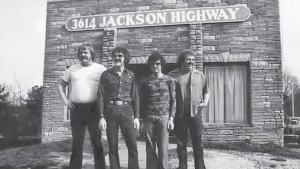

What they all have in common is a studio band called “the Swampers”: bassist David Hood, drummer Roger Hawkins, guitarist-engineer Jimmy Johnson, keyboardist Barry Beckett (and often Oldham).

When Paul Simon turned up for his session, he also was surprised to find that all the players were white: such feel players had to be black, surely. Weren’t Southern whites crackers who liked country?

Well yes, but they also grew up listening to R&B and – when they could get away with it in the days of segregation – mingling and making music with black players.

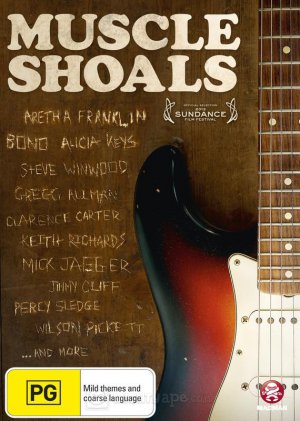

Civil rights is one of the few

angles not explored in depth in Greg Camalier’s moving 111-minute

documentary Muscle Shoals (now out on DVD through Madman) – there is only a brief hint of I’ll Take You

There – possibly because the racial breakthroughs that occurred

in the studio are expressed in the grooves of the music.

Civil rights is one of the few

angles not explored in depth in Greg Camalier’s moving 111-minute

documentary Muscle Shoals (now out on DVD through Madman) – there is only a brief hint of I’ll Take You

There – possibly because the racial breakthroughs that occurred

in the studio are expressed in the grooves of the music.

The documentary’s narrative is dominated by the story of Rick Hall, and its pace is driven by the irresistible rhythm of all those swampy hits. Hall is an intimidating, headstrong, self-taught perfectionist with appalling luck. To him, “dirt poor” is not just an adjective: his parents’ cabin had no floor.

“We grew up like animals,” he says. Death, abandonment, car crash, fights, fall-outs and competitors all played a part in shaping this headstrong man.

We hear his dreadful stories, plus those behind Muscle Shoals’ greatest hits. Patches is a key text (sung by Clarence Carter, it is actually Hall writing about his own life), and besides Franklin, Pickett and Sledge, there is Etta James’s menacing Tell Mama and, much later, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Freebird (originally created in Muscle Shoals).

The first of many carpet-baggers who came to town to borrow a little Shoals magic were the Rolling Stones, whose brief 1969 visit generated two of their finest moments (Brown Sugar and Wild Horses).

What would Exile on Main Street have been like if, as intended, it was recorded there rather than a dank basement in the South of France? (Rural Alabama was no Marseilles when it came to heroin, pot and booze.)

Besides Paul Simon and Bob Dylan, other visitors who secured hits there include the Osmonds (One Bad Apple), Bob Seger (Old Time Rock’n’Roll), and Rod Stewart (half of Atlantic Crossing). Plus, to my surprise, Jimmy Cliff’s gracious Sitting in Limbo which, like most of these songs, floats gently on the delicate drumming of Roger Hawkins. (Understandably left out is the fact that Max Merritt recorded a version of Steely Dan’s Dirty Work there.)

We are in a golden age of music documentaries. Since George Martin pulled back the sliders in The Making of Sgt Pepper in 1987, getting inside the music is required (as opposed to “behind it”, VH1-gossip style). With the Stax story Respect Yourself, this is the Southern answer-doco to Standing in the Shadows of Motown.

Muscle Shoals features the requisite talking heads. Jerry Wexler – who took Pickett, Franklin and Dylan there – is of course essential. The way Southern culture infiltrated the personality of this tough-talking, intellectual Brooklyn Jew comes through in his language (before the fight between Rick Hall and Aretha’s husband, they were “drinking from the same jar”).

Usefully there are

comments from Keith Richards (looking like a marinated walnut) and

Steve Winwood (who uses the word “enigma” to explain the mystery

of Muscle Shoals). Inevitably there is the ubiquitous, redundant

Bono, who waffles on about how the town’s “alchemy turned rust

into gold”.

Usefully there are

comments from Keith Richards (looking like a marinated walnut) and

Steve Winwood (who uses the word “enigma” to explain the mystery

of Muscle Shoals). Inevitably there is the ubiquitous, redundant

Bono, who waffles on about how the town’s “alchemy turned rust

into gold”.

Wilson Pickett was worried when Hall picked him up at Muscle Shoals’s tiny airport, and saw black workers still picking cotton in the fields. Then he found his mojo playing with white players; if they had hung out on the street together, Pickett would have attracted the police. Of Roger Hawkins he says, “That drummer was fantastic! He wasn’t wearing himself out.”

Because Hall’s extraordinary story dominates, Muscle Shoals doesn’t quite take you inside the staves in the way that Standing in the Shadows of Motown did. But it has an emotional heft lacking from the workmanlike Twenty Feet From Stardom.

Besides unforgettable music, a great music documentary requires drama and an unforgettable character.

Muscle Shoals has all three.

Chris Bourke in a Wellington broadcaster and writer who wrote Something So Strong, a biography of Crowdd House, and Blue Smoke; The Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music 1918 - 1964which won the New Zealand Post Book of the Year award in 2011. His website is here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work.

Tony Walker - Jun 25, 2014

gonna check it out - sounds good

SaveTania Wilson - Jun 25, 2014

Sounds excellent! ;]

SaveIan Strickland - Jun 28, 2014

I've seen it and loved it! One of my favourite music docos of all time. Recommended!

SaveJeremy - Jul 2, 2014

Absolutely superb doco. On top of all of the above it also covers Duane Allman - pre-Allman Brothers, pre-Derek And The Dominoes laying down his legacy with Aretha, Wilson Pickett, and that sublime slow blues (Loan Me A Dime) with Boz Scaggs.

Savepost a comment