Jeffrey Paparoa Holman | | 5 min read

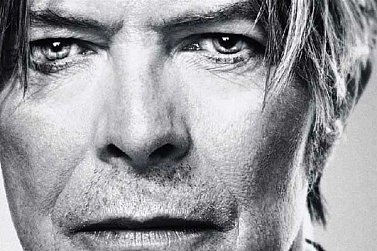

In the tidal wave of emotion that has swept the world since David Bowie’s death was announced, I have found my myself in a curious position: saluting a great artist who I never really got know, or cared enough about.

Certainly I knew of his music and songs in the Seventies when many of my young druggie friends would turn up at my place and play them, but they were a good five to 10 years younger than me.

They had been struck in the heart by his lightning: my electric shock had happened a few years before in the early-to-mid Sixties when I first heard Bob Dylan and those powerful bolts of energy – where a 14-16 year old mind is transformed by such an encounter – had already surged through me.

I was born in November 1947, in London, Kingston-on-Thames, not terribly far away from Brixton where the ten month old David Robert Jones was about to endure his second English winter in the chill of a battered post-war England. In May 1950 when he was three years old, my mother and my brother and I stepped aboard an immigrant ship to New Zealand and my ways and Bowie’s were geographically set apart.

Both of us were born into a lower

middle-class-cum-working class suburbia and it would stand to reason

that being peers in age, I might have had more in common with him

than a descendant of European Jews brought up in a comfortable middle

class America of the Forties, way up in the mining town backblocks of

the Mesabi Range in Minnesota.

Both of us were born into a lower

middle-class-cum-working class suburbia and it would stand to reason

that being peers in age, I might have had more in common with him

than a descendant of European Jews brought up in a comfortable middle

class America of the Forties, way up in the mining town backblocks of

the Mesabi Range in Minnesota.

Not that reason or sense has a lot to do with our choices and even less when it comes to others’ moves. Even though I heard Dylan first, it could be argued I should have had more in common with Bowie by birth and temperament and even my natal culture.

My parents remained English, and I lived a working class life; I was something of an outsider who didn’t fit but desperately needed to belong. But I was not in London now, I was in New Zealand and that Fifties macho culture had done its work.

I could handle Dylan: he had something of the frontier about him in those early records and even when he went urban electric, he held me in his thrall.

The truth is, I’d been struck by lightning almost ten years before Bowie hit me and for some people, in adolescence, that only happens once.

Sure, there were the Beatles and the Stones, I loved Procol Harum, the Yardbirds and plenty more – but it was only Dylan that made me want to be something I wasn’t yet. He woke the urgent need to write, to write poetry – and it’s never gone away. He’d been shaped by the James Dean imagery of his day which was still around when I hit high school and later, in my callow sixth form cynicism.

I’d found in this man a strong ancestor; even though I lost him as I went through various incarnations in search of a self I could be – failing to escape from the bully jocks of my childhood by doing the kinds of jobs they did, to fit in – I never lost his example, his following of a road his own.

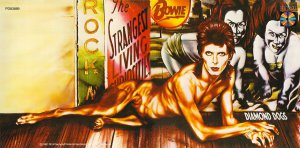

Thinking about it now, in the Seventies when I first saw the album covers of records like Aladdine Sane and

Diamond Dogs, it was too weird for me and the music never took hold;

it was just there in the room while we got stoned.

Thinking about it now, in the Seventies when I first saw the album covers of records like Aladdine Sane and

Diamond Dogs, it was too weird for me and the music never took hold;

it was just there in the room while we got stoned.

I don’t think my Kiwi conditioning machine from the Fifties would have allowed me out of its straight jacket back then and I don’t think I’m alone. Come the Eighties, I was deeply into a conservative evangelical Christian change and so Bowie – along with a whole lot of others – was off my radio.

Dylan turned up Saved too, so he was an artist from my old life that kept getting through. A return to England in 1987 and ten years there, with six of them bookselling in central London gradually shifted the gravity of my Kiwi identity into some kind of neutral. I became more open while retaining a working faith, pivoting more and more around my recovery from alcoholism.

I guess I could say I ended up in London working with a lot of David Bowies: people on the edge, booksellers who wanted to be writers, actors, musicians, artists – anything in fact but bloody booksellers. For many of us, it was all we could find to get by; but I did get to meet a lot outsiders who affirmed the outsider in me, the leftover rebel who’d dropped out of high school and university (twice), the wanna-be-poet still held down by the great New Zealand clobbering machine of Depression and World War Two experiences that had shaped our elders.

I saw great writers read and heard poets you would cross rivers to encounter: Derek Walcott and Joseph Brodsky, Ivan Klima and Jeanette Winterson. I stood before Salman Rushdie as he signed a book for my son; I made a cup of tea for Tony Benn. I had found my tribe at last.

I would write drafts of poems in a little cafe across the road from my Waterstone’s branch on 121-125 Charing Cross Road, while in another cafe on the other side, Dylan Horrocks would be drawing his Pickle comics.

I had published nothing for nearly 20

years, but I was home.

I had published nothing for nearly 20

years, but I was home.

In 2012, writing finally took me to Berlin: Bowie’s Berlin, it would turn into for me, as I traveled on the S7 from Grunewald to the Goethe-Institut in Neue Schönhause Straße for my language lessons, with his new song, Where Are We Now haunting me in the headphones – “The moment you know, you know, you know…”.

David Bowie had caught up with me and I with him; this wasn’t like the Dylan lightning strikes of 1965, more the rich melancholy of a grateful old age.

And now I know this, I can return to his huge catalogue and explore; it is always too late, it is never too late, it is always now.

I’m going to start with the German version of Heroes in the link below and see if I can find a new hero by the fallen Wall, where I have since 2012, in awe and honor, stood.

“Dann sind wir Helden für deisen Tag/Then we are heroes for this day”

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman is an award-winning Christchurch-based poet, novelist and non-fiction writer who lectures in English at the University of Canterbury.

His most recent work includes Best of Both Worlds: The Story of Elsdon Best and Tutakangahau (published by Penguin in 2010) and The Lost Pilot, a memoir about his relationship with his naval veteran father and a kamikaze attack on his aircraft carrier, HMS Illustrious in April 1945 (see here).

The Best/Tutakangahau book is a non-fiction work which delves into the 1895 meeting in the rugged Urewera ranges between Best, a self-taught anthropologist and quartermaster, and Tuhoe chief Tutakangahau, which would have lasting effects on our views of traditional Maori society.

This article above is reproduced from Jeffrey's blog (here) with his permission, for other pieces by him at Elsewhere see here.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work.

post a comment