Graham Reid | | 6 min read

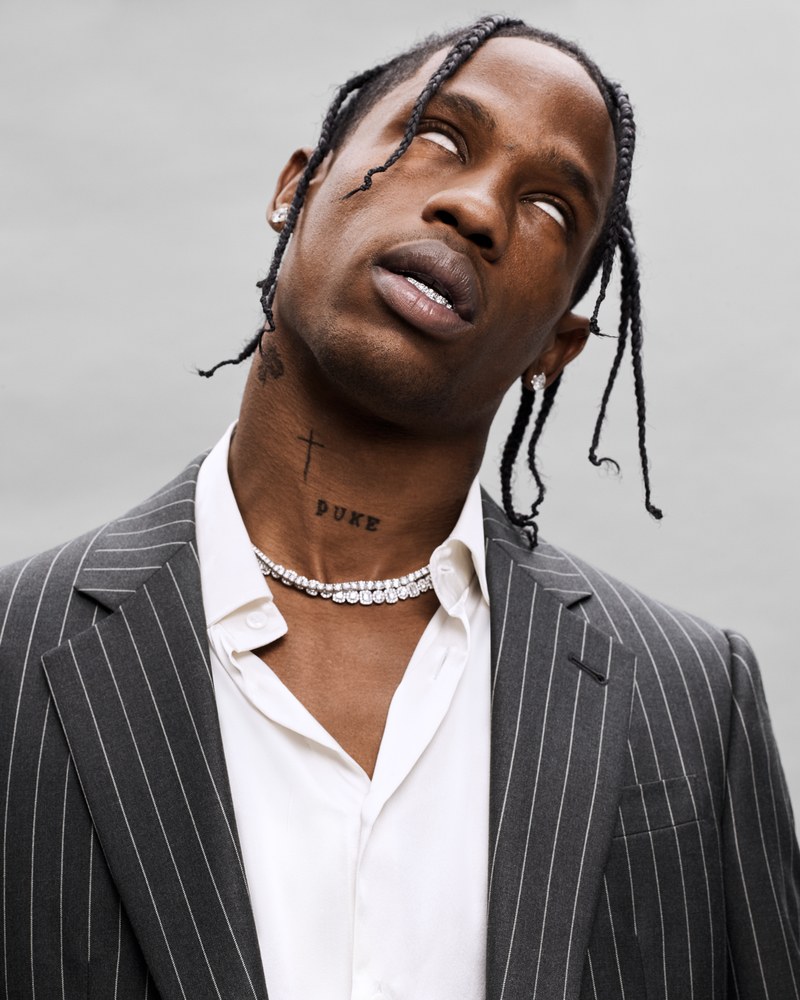

Travis Scott plays the magician in his 2018 album Astroworld, crafting an underworld of slurred auditory hallucinations for his audiences.

A Houston rapper true to his roots, Scott’s musical success led to unhindered access to the drugs and alcohol he has been glorifying along the way. His most recent album leaps beyond his previous solo work and numerous features on fellow artists’ as it embodies the brand-obsessed zeal overtaking young entrepreneurs now -- from typical album merch to a full-blown theme park for the release, Scott is truly the king of his own psychedelic world.

Aptly designated one of the most successful “drug albums” of the year, Astroworld does not deny Scott’s long-time fans the bass-bleeding riot tracks he has served since his breakout. Among the album’s best are Sicko Mode (featuring Drake) and No Bystanders (Sheck Wes, Juice Wrld), both of which readily incite the sometimes physically dangerous concert mosh pits Scott’s tours are known for.

Aptly designated one of the most successful “drug albums” of the year, Astroworld does not deny Scott’s long-time fans the bass-bleeding riot tracks he has served since his breakout. Among the album’s best are Sicko Mode (featuring Drake) and No Bystanders (Sheck Wes, Juice Wrld), both of which readily incite the sometimes physically dangerous concert mosh pits Scott’s tours are known for.

However, the album delivers more than the traditional rap boasting of women and money. Scott’s mission for his album was to convey the experience of “taking an amusement park away from kids”, and the sinister synthetic instrumentals and characteristically angelic vocals of Swae Lee and The Weeknd commercialize the private trip Scott enjoys daily.

Scott’s project is a personal one.

The original Houston theme park, AstroWorld, was torn down for apartment development. The rapper felt the city’s fun was robbed, so his album reintroduces it in a new medium.

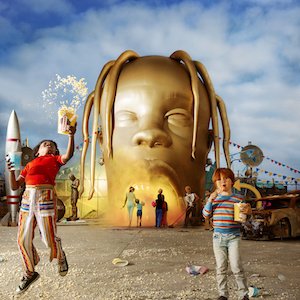

The album’s cover art depicts the park’s entrance with his own golden head erected behind retro-dressed kids, but trash strewn about and a dilapidated car suggest decay in the city. For a loyal artist, bringing glory back to his roots is a privilege.

Complemented by dreamy vocal styles are the drug-infused lyrics themselves. With lines like “I did half a Xan’, thirteen hours ‘til I land” and “Spent ten hours on this flight, man / Told the pilot ain’t no flight plan” draw a continued allusion of flying to depict his undisturbed highs. This marks a new generation of party albums, one in which any single person can immerse themselves in the hallucinogenic experience of the expensive and illegal drugs so accessible to the rich and famous -- in the comfort of their own home.

Complemented by dreamy vocal styles are the drug-infused lyrics themselves. With lines like “I did half a Xan’, thirteen hours ‘til I land” and “Spent ten hours on this flight, man / Told the pilot ain’t no flight plan” draw a continued allusion of flying to depict his undisturbed highs. This marks a new generation of party albums, one in which any single person can immerse themselves in the hallucinogenic experience of the expensive and illegal drugs so accessible to the rich and famous -- in the comfort of their own home.

Astroworld packages and exports the drug user’s inherently personal trip through descending minor chords and eerie echoes. Scott’s trademark style of enhancing rapped and sung lines with heavy auto-tuning lends itself to the superficial illusion his music creates.

The artist describes a life in which the pseudo-reality of a warped mind on lean has come to replace a sober existence as truth. Such a phenomenon is not uniquely Scott’s contribution to the rap world, as artists such as Lil Xan have collectively encouraged an invasive shift in the genre’s drug culture. While not entirely abandoning the classic ‘Nineties narrative of selling on the streets championed by greats such as the Notorious B.I.G and Tupac, contemporary tracks instead revere the mind-numbing powers of prescription drugs.

Lean, drank, Xans, and others slip their users into a colorful dream devoid of the responsibilities of their unbearable realities.

This transition has not gone without consequence. While Scott may be enjoying a peak in his career and walking a line close to his body’s chemical capacity, other major names have dropped from that unconscious vacation into permanent absence. The threat of overdose looms at each trip, and the recent deaths of Lil Peep and Mac Miller foreshadow what may come of Scott and his overzealous followers. The rap community heavily mourned these losses and many others, yet Astroworld blatantly glorifies such a lifestyle.

Throughout his album, Scott pays homage to icons of his southern hometown, including the late DJ Screw. In Scott’s track R.I.P. Screw, the artist speaks to his musical icon who invented his signature “chopped and screwed” style of rap. One sound bite on the song was lifted from DJ Screw’s popular track South Side, honoring his and Scott’s shared hometown.

Screw crafted the influential “chopped and screwed” style that defines Astroworld; a slurred and dreamy effect arises from slowing the tracks' tempo and drawing out certain notes.

Scott’s reverence for DJ Screw is perfectly ironic as he perpetuates the exact path that brought about his inspiration’s demise. For those who are so financially secure through their musical success, the basic themes of status and money are almost childish. Scott reigns from a position of such unimaginable abundance he has to search for the next thrill, one not provided by the run-of-the-mill weed and coke medley.

It’s not like he’s above sex and money. Scott is, in fact, in a serious relationship (that is, co-parenting) with the business mogul and queen of female sensuality, Kylie Jenner. The rapper references his wifey’s fame in the opening track, Stargazing, because he “know my baby mama is a trophy”. The near-billionaire beauty mogul also cameos in the music video for “Stop Trying to be God. Scott knows he snagged one of the most desirable women of his generation, and he’s not afraid to flaunt her to his own advantage. He’s not just googly-eyed -- he’s a businessman.

It’s not like he’s above sex and money. Scott is, in fact, in a serious relationship (that is, co-parenting) with the business mogul and queen of female sensuality, Kylie Jenner. The rapper references his wifey’s fame in the opening track, Stargazing, because he “know my baby mama is a trophy”. The near-billionaire beauty mogul also cameos in the music video for “Stop Trying to be God. Scott knows he snagged one of the most desirable women of his generation, and he’s not afraid to flaunt her to his own advantage. He’s not just googly-eyed -- he’s a businessman.

The success and innovation of Astroworld come not from the story it tells but the physical sensation it conveys.

The chopped and screwed style characterizing Scott’s album creates a mellow audio experience similar to a trip off lean; slow pronunciation and tempo mirror the brain’s delayed and drowsy perception on the drug. Swae Lee’s auto-tuned falsettos coupled with muffled synth pad notes create a warped sound. 808s drive vibrations while high hats and snares deliver a concrete beat to add a radio-friendly pop to the otherwise distorted swirl of wavering melodic vocals. Sliding synths contribute a floating feeling, drifting up in pitch and carrying the audience into a transcendent state. Scott’s sound throughout his musical career often features a synthetic bass-toned hum growling in the background, an otherworldly accessory to the lighter vocals he has mastered.

Astroworld would not be complete without its A-list vocalist and producer features. While Scott has been criticized of padding his own incomplete style with the more recognizable contributions of others in order to secure an audience, his ability to leverage his connections to round out the multi-faceted album is downright crafty. He aims for Astroworld to be a complete experience for listeners, and any artist can acknowledge that a solo project will only cater to so many moods. Instead of overextending his personal style, he supplements his work with Drake’s pop sinkers, Frank Ocean’s emotional ballads, and Quavo’s hip hop bravado.

It’s not cheating; it’s a strategic business move.

Travis Scott’s album mirrors the lifespan of a drug trip; the invincibility of its best hype tracks delivers a blinding high, while the rolling vocal ranges of unpredictable guest artists take listeners down an unpredictable path. Scott’s power as a rapper lies within his ability to conceive an entire world for his audience. All it takes is 58 minutes before we are inevitably hooked on his lifestyle, and he’s got thousands clamoring for tour tickets (expecting roller coaster rides as promised, and maybe a chance to see him arrested again).

That’s the beauty of Astroworld -- it can carry a near-violent crowd to hysteria or hum the backdrop to a night in, and Scott’s got everyone addicted.

Rachel Edwards is a student at Georgetown University in Washington DC and studied at the University of Auckland for a semester.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging

post a comment