Graham Reid | | 6 min read

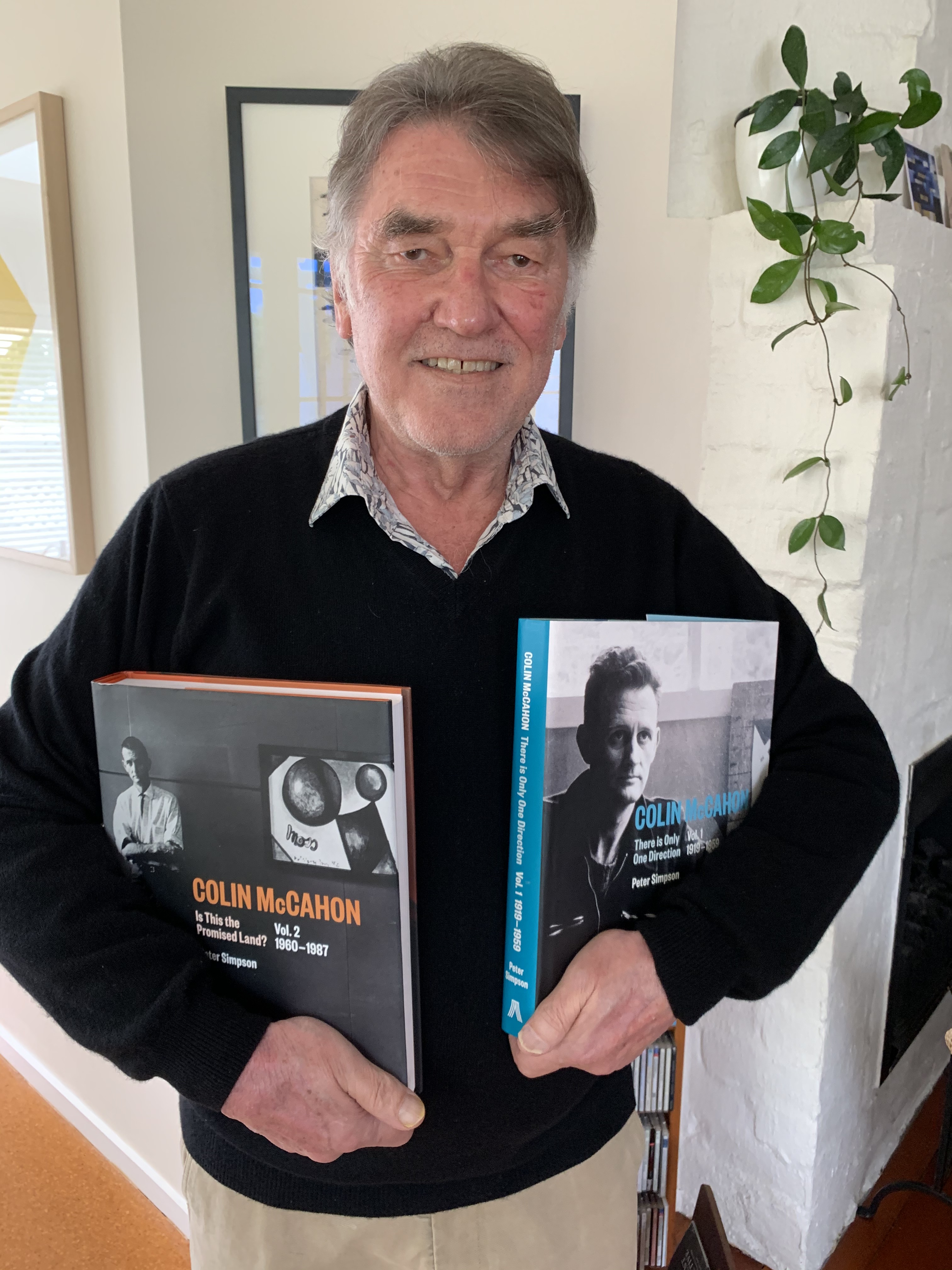

This is an edited extract of the speech Peter Simpson gave at Gow Langsford Gallery, July 28 2020 on the launch of the second and final volume of his biography of Colin McCahon, Is This The Promised land? Vol II 1960 - 1987.

.

I would like to say something about the methodology which I followed in the books and focus on just one brief sequence in McCahon’s career to describe some of the research and discoveries that shaped my treatment of it.

The moment I’ve chosen comes in the first chapter of my new book and concerns McCahon’s turning away from geometric abstraction back to realist landscape in about 1962.

McCahon started the 1960s by striking out boldly in a new direction – that of geometric abstraction in the extensive Gateseries. This moment is exemplified in the landmark painting, Here I give thanks to Mondrian (1961).

But soon after inventing his “new painting” as he called it, McCahon started pushing restlessly at the limits of abstract painting, as if frustrated at its restrictions.

But soon after inventing his “new painting” as he called it, McCahon started pushing restlessly at the limits of abstract painting, as if frustrated at its restrictions.

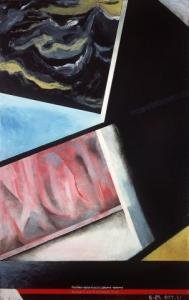

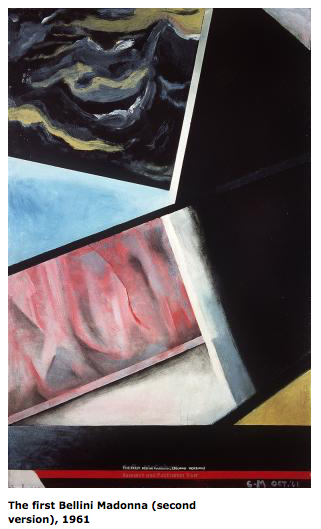

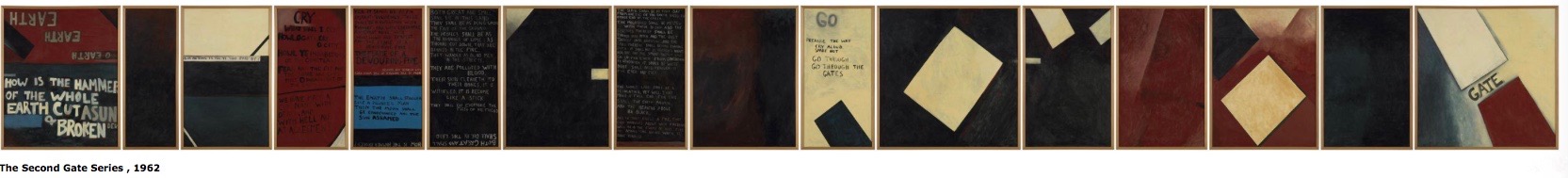

In the Bellini Madonnas of 1961-62, he introduced references to art history and religious symbolism into pure abstraction, and soon afterwards (1962) he created a major series, The Second Gate Series (16 panels) in which he brought in biblical texts to join abstract panels, as provided by John Caselberg from the Old Testament prophets.

This was in order to help convey his burning message about the threat of nuclear warfare.

“I will need words,” he famously told Caselberg.

McCahon had discovered he wanted his paintings to say more than was possible with pure abstraction, with shape and colour and texture alone. He needed symbolism, text and art historical reference to help convey his meaning.

To put it another way, he embraced impurity– not the purity of a Mondrian -- as his aesthetic ideal.

The Second Gate Series was exhibited in Christchurch in 1962 in an show organised by Ron O’Reilly. But McCahon was rather disappointed with the reception, and in particular with the review in The Press by J.N.K. [Nelson Kenny], normally the most astute and enthusiastic of McCahon’s reviewers.

Among the things Kenny said were: “Simply as paintings some of the panels are much below Mr McCahon’s best …When one reads them, the eye following the words as it does on the printed page, all is well.

“But when the text has been perceived and the eye begins to study the object itself, then weaknesses become apparent.

“But when the text has been perceived and the eye begins to study the object itself, then weaknesses become apparent.

“On the whole the series must be described as a near miss in an attempt to bring off something new and grand…”

McCahon wrote to O’Reilly: “I must admit I felt rather foolishly annoyed by [Kenny] & his comments. There was no reason why he should have seen more – or other – than he did, but his writing suggested an almost preferred refusal to understand.

“Not that it matters finally, but after lots of work one does like to be flattered.”

McCahon was particularly concerned about the way Kenny had gone about his interpretation – reading the texts from left to right and then and only then responding to the work as a whole.

McCahon thought this was putting the cart before the horse, and commented to O’Reilly, “the whole is to be looked at firstly, then the parts, that the eye moves along the wall & reading as it moves, misses more than it gains.

“Reading follows the visual impact & should not precede it – that of course, I realise, is almost impossible – but ideal. But to return to the first: after this almost inevitable first reading this quite separate function of looking should happen . . . I’m sure it is only on this level that the ‘sense’ does appear.”

Now, this comment flies in the face of the conventional wisdom about McCahon’s very long works.

Critics usually quote his comment in a letter after seeing Jackson Pollock’s vast Autumn Rhythm in New York: “It gave me the idea of pictures for people to walk past”.

Anyway, this critical response to The Second Gate Series affected McCahon so deeply that he changed direction.

In a lecture he gave at that time he was reported as saying the work was unintelligible to Christchurch viewers who saw it. The paintings misfired, and this worried him.

He came to the conclusion it was essential to find a way of communicating to people. He must go back and start again from scratch – to the Otago Peninsula paintings in fact.

He was looking for a feeling of order that he had realised in them.

He was looking for a feeling of order that he had realised in them.

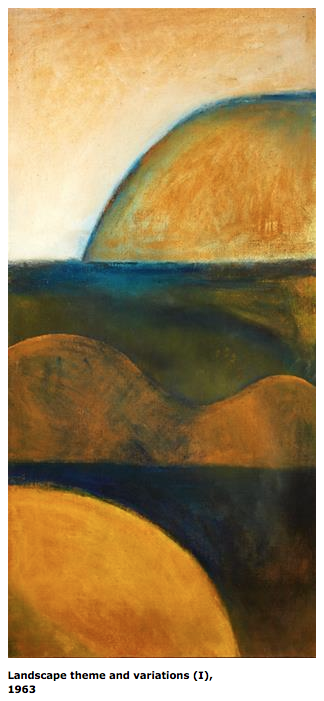

This resulted in a return to landscape in the 1962 Northland series which led on to the two great series Landscape Theme and Variations (Series A & B) each of eight panels the following year.

He talked of these works as “a return to ‘realist’ painting but a realism impossible without the previous work.”

The point of this story is to demonstrate the value of digging into the archive in order fully to understand McCahon’s work. In this case the archive is represented by newspaper reviews of the time, and by McCahon’s letters to friends such as Caselberg and O’Reilly, or to reports of talks he gave as preserved in library archives.

This is the guts of my approach.

I’ve done an awful lot of digging into libraries and archives, uncovering evidence of what happened and putting it all together. A process justified by the results, I believe.

In this case a new more detailed and nuanced understanding of a key phase in his career and of how he wanted his larger works to be responded to.

I will conclude with some words by Charles Olson, the American poet and scholar, about how to go about historical or biographical research.

Olson had written a famous book about Herman Melville (Call Me Ishmael), also a favourite writer of McCahon’s. These words for years have been a kind of mantra for me. You’ll have to excuse the rather old fashioned hipster and sexist rhetoric.“Dig one thing or place or man until you yourself know more about that than is possible to any other man. It doesn’t matter whether it’s Barbed Wire or Pemmican or Paterson or Iowa [or Colin McCahon]. “But exhaust it. Saturate it. Beat it. And then U KNOW everything else very fast: one saturation job (it might take 14 years). And you’re in, forever.”

Olson had written a famous book about Herman Melville (Call Me Ishmael), also a favourite writer of McCahon’s. These words for years have been a kind of mantra for me. You’ll have to excuse the rather old fashioned hipster and sexist rhetoric.“Dig one thing or place or man until you yourself know more about that than is possible to any other man. It doesn’t matter whether it’s Barbed Wire or Pemmican or Paterson or Iowa [or Colin McCahon]. “But exhaust it. Saturate it. Beat it. And then U KNOW everything else very fast: one saturation job (it might take 14 years). And you’re in, forever.”

Well, my saturation job on Colin McCahon took a good deal longer than 14 years (let’s say 30 years minimum), but the statement otherwise holds true.

I’m proud of these books; I gave them my best shot; with such a great subject I could hardly do less.

And if they honour a great artist in an appropriate way, I’ve done my job.

.

Peter Simpson's books are Colin McCahon: There is No Other Direction Vol I 1919 - 1959 ($80) and Colin McCahon: Is This The Promised Land? Vol II 1960 – 1987 ($80)

Both published by Auckland University Press.

All quotations are from Peter Simpson, Colin McCahon: Is This the Promised Land? 1960-1987 (AUP, 2020)

These and other other books by Peter Simpson have been reviewed at Elsewhere here.

.

Peter Simpson is a former associate professor of English at the University of Auckland. He is the author of numerous critically acclaimed books, including Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years, 1953–1959 (Auckland University Press, 2007) and Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933–1953 (Auckland University Press, 2016). He has also curated three significant exhibitions of McCahon’s work. He received the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement (non-fiction) in 2017.

.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work. It is wide-ranging.

post a comment