Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Ballad of the Skeletons

It was in my early twenties, an American Literature lecture at the old University of Canterbury townsite that I first heard Allen Ginsberg’s poetry read aloud, complete with an unheard of lecture hall profanity when David Walker our teacher, a poet himself, read us the poem America, from Howl and other Poems. He launched into the subject with, “America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.”

Then the fifth line. “Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.”

Boom!

I’d heard plenty and spewed plenty of F-bombs in my short life, but you didn’t do this stuff in the halls of learning back then, even now, perhaps. He went on to read sections of Howl, the title poem, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving, hysterical, naked...”. Wow! I was hooked.

Ginsberg - along with David himself, who became a lifelong friend until his death in 2008 - were now a pair of tutors and spirit guides. All I really wanted to do with my life - which then, I did not, could not understand - was to write poetry. I started, in a stuttering beginning, but I was on the road (so to speak) and have managed to stay the course so far.

Fast forward to 1995, in London four years, working in a bookshop where I’d earlier met the cartoonist Dylan Horrocks -- like me, a struggling expat-Kiwi wanting to practice his art, both of us selling books for Waterstones to make ends meet.

London, a mecca of performance 24/7, 365 days of the year, had attracted back my early hero Ginsberg after a thirty year performance break from his June 1965 gig at the Royal Albert Hall, when sixteen poets performed to an 8,000-strong crowd in The First International Poetry Incarnation.

They’d even been over to Prague that May and performed their work, Ginsberg arrayed as Kral Majales, the May King, until the Communist government kicked them out. Here he was again with a bunch of other poets, still on the road, for The Return of the Reforgotten; same venue, a near seventy year old veteran, who had been here, there and everywhere in the meantime.

If you watch the Bob Dylan video of Subterranean Homesick Blues below, as the singer riffles through the lyrics, a figure talks to another on the left of the screen; then as Dylan throws away the last cue card, this man walks away down the street behind him. Ginsberg.

Here he was then, at the Royal Albert Hall, London, 16 October, 1995, and I was taking my 21-year old daughter in her Goth incarnation to see this hero of alternative culture perform.

Time had winnowed the crowd: there were only 2,000 of us this time, but nothing had dimmed the enthusiasm, as the brave supporting act poets read, and we waited for Ginsberg. On he came to a roar, a standing ovation and he kicked into reading.

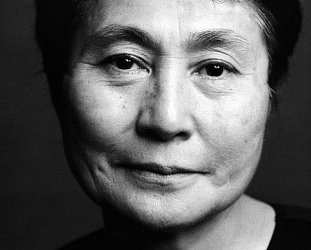

The place went nuts as the two settled into a performance of The Ballad of the Skeletons (you can watch it here). What a night.

In January 1997, I returned to New Zealand and went back to finish that degree, abandoned in the mid-70s. Writing poetry by now as if my life depended on it, we heard the news in April of Allen Ginsberg’s death at the age of seventy.

Vale, Allen, you blazed a trail. Haere rā e te rangatira! So I wrote him this poem.

Ginsberg (1926-1997)

|

|

The limp sunflowers from Wai-Ora, we tossed out. I saw you, last year, in London: old, dying, young. Singing, chanting, swaying: a Hassid gone astray.

|

.

.

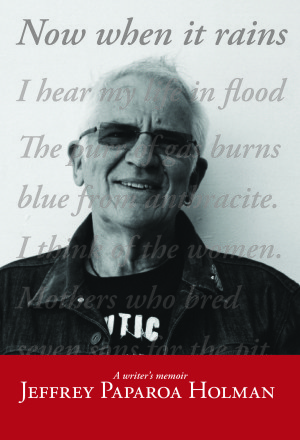

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman is an award-winning Christchurch-based poet, novelist and non-fiction writer who lectured in English at the University of Canterbury.

Among his recent work has been Best of Both Worlds: The Story of Elsdon Best and Tutakangahau (published by Penguin in 2010) and The Lost Pilot, a memoir about his relationship with his naval veteran father and a kamikaze attack on his aircraft carrier, HMS Illustrious in April 1945 (see here).

The Best/Tutakangahau book is a non-fiction work which delves into the 1895 meeting in the rugged Urewera ranges between Best, a self-taught anthropologist and quartermaster, and Tuhoe chief Tutakangahau, which would have lasting effects on our views of traditional Maori society.

The Best/Tutakangahau book is a non-fiction work which delves into the 1895 meeting in the rugged Urewera ranges between Best, a self-taught anthropologist and quartermaster, and Tuhoe chief Tutakangahau, which would have lasting effects on our views of traditional Maori society.

Elsewhere reviewed his 2017 collection Dylan Junkie (here)

For other contributions by him at Elsewhere see here.

.

The illustration here by Dylan Horrocks is used with permission and appeared in Holman's 2018 memoir Now When It Rains. See here.

.

Elsewhere previously posted a piece about the recording of GInsberg, McCartney and others of the poem Ballad of the Skeletons (here, audio at the top of this article), which prompted this memory by Holman. We thank him for it.

.

Other Voices Other Rooms is an opportunity for Elsewhere readers to contribute their ideas, passions, interests and opinions about whatever takes their fancy. Elsewhere welcomes travel stories, think pieces, essays about readers' research or hobbies etc etc. Nail it in 1000 words of fewer and contact graham.reid@elsewhere.co.nz.

See here for previous contributors' work.

.

post a comment