Graham Reid | | 13 min read

In 2001 I traveled to Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, on serious Herald business.

The background was interesting: the Kuomintang party (KMT) which was mired in corruption (“black gold” in the local parlance) had governed for 50 years but had recently lost the election to the DPP (Democratic Progressive Party).

I suggested to my editor someone – me – should go up and check out what things were like a year on.

He accepted the idea as long as I could find a way to fund the trip. So I approached the Asia 2000 Foundation (now the Asia-Pacific Foundation) and they agreed to help with airfares.

Accommodation and expenses would be my problem and aside from paying my wages when I was away for a week I recall the Herald punted up some small amount. A very small amount. I knew I was largely going to fund on-the-ground expenses myself.

I was good to go, arranged interviews – one with the premier, quite a few with bureaucrats and top people in the DPP and KMT – and then applied for a week's holiday at the end of my time in Taipei. That would mean I could travel around the country for a week on my own.

It was an excellent and productive trip – I got four major Herald stories out of it – and I got to see some of the country.

When I returned to noisy Taipei I stayed in a cheap hotel (a brothel actually) which I wrote about here.

But while first in Taipei with a lovely and anxious minder I was obliged to find very – I emphasize, very – cheap digs.

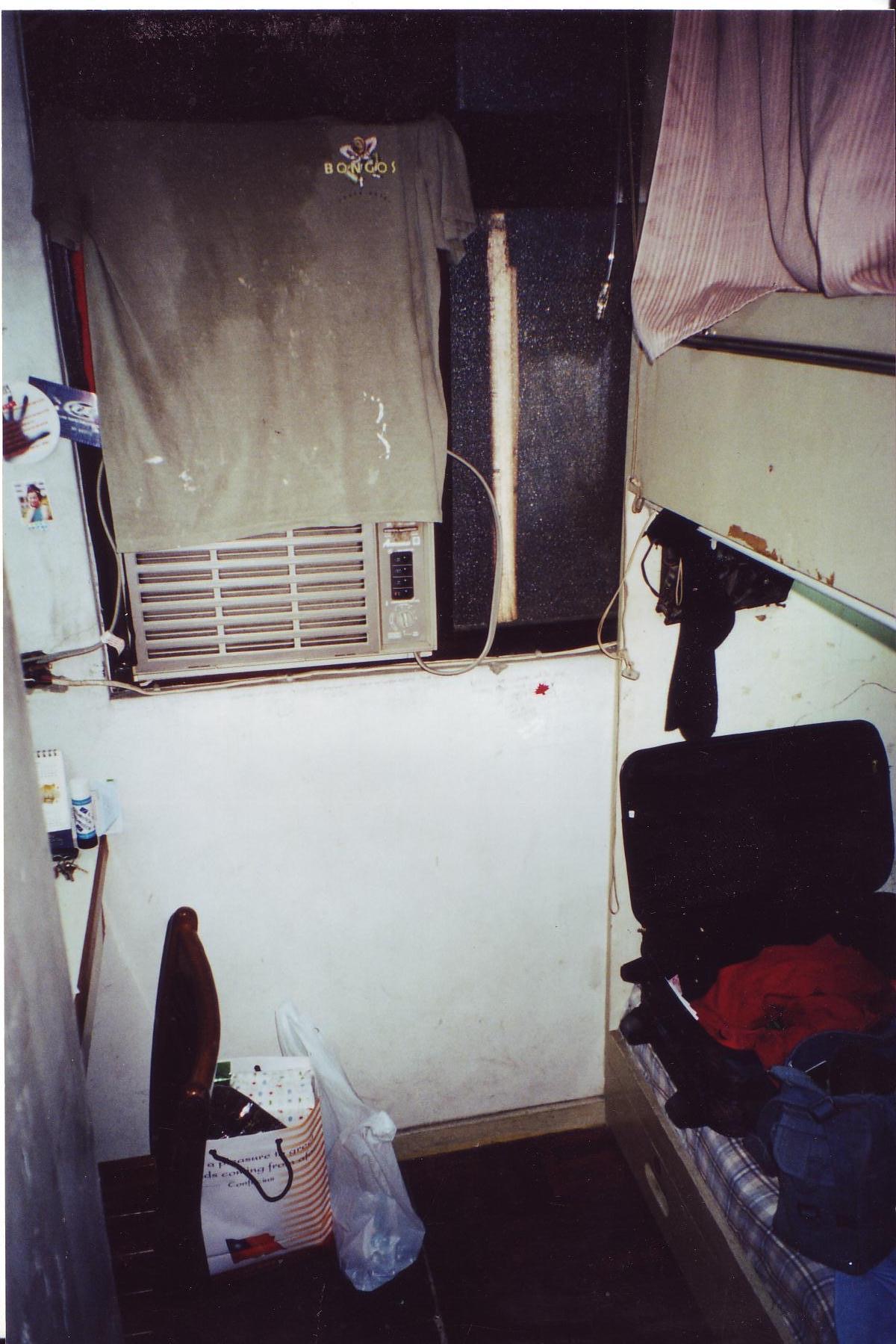

That was when I saw the room I knew I could die in. The air-conditioner blocked the only window and the door lead through another room then past the fire-in-waiting area called "the kitchen" before you even got close to the stairwell.

It was all a lot of fun and seriousness, and my minder was thrown into a panic when I told her after the first week there that I wasn't going back to the airport to fly home but would be traveling around the country by myself.

I survived.

Just.

.

These entries are of little consequence to anyone other than me Graham Reid, the author of this site, and maybe my family, researchers and those with too much time on their hands.

Enjoy these random oddities at Personal Elsewhere.

.

THE GREEN SILICON ISLAND

The premier of Taiwan is late.

It has been an awkward morning of delays and apologies, of exchanging cards, and of old men warily watching me while I wait for the premier to arrive for our interview.

There have been a number of false alarms as yet another man in dark suit and thick glasses enters and I keep leaping to my feet in case this is him. I am working from two photographs imprinted in fallible memory. And he has any number of doppelgangers.

Then, anticipated by a flurry of nervous excitement, he arrives and the room becomes a swirl of energy and furiously pumped hands.

There is much bowing, then shuffling of seats as the half dozen stone-faced bureaucrats in dark suits settle down and resume staring impassively at me as I take my chair beside Mr Chang Chun-hsiung.

We are in a grand first floor government office with ornate carvings, that heavy furniture the Chinese favour and a tray of untouched tea cups.

While waiting, shifting uncomfortably inside my new suit and trying to decipher the artwork, I have also flashed furtive glances at the young Chinese woman who is to be my translator. She is transparent.

Her hair is pulled back so tightly that when I look at her directly all I can see is a thin dark outline, like a pencil line, around her forehead and a face so pale it is disappearing before me.

Her skin is white, her jacket and skirt the same.

She is an ethereal, pale lily dissolving into air even as I look at her.

She sits between, but slightly behind, the premier and me and whispers the translations. Again, she is present but not actually there.

When our formal meeting is over -- a polite but largely superficial discussion of relations with China, the changed political climate with the Bush administration, and some laughter about the depth of corruption in this tiny island of some 23 million -- the premier and I have our photograph taken together with our transparent translator standing between, but slightly behind, us.

With another handshake and an engaging laugh he says, “You are my best friend from New Zealand.”

Even the old bureaucrats crack smiles.

Much later my photographs come back. I flick through them -- that temple, that construction site, that museum, and that piece of barbed wire along the inhospitable western coast -- and then I come to the one of the premier and me.

And the translator is not there.

She has faded away, as I feared she might.

“This is where the two tourists were killed last month,” says my tawny, tough guide as we stand on the lip of a rock overlooking the swirling river below.

“Where? Along here?” I gesture optimistically along the narrow path between the marble mountains of this deeply forested gorge.

“No. Here.”

And she points to exactly where we are standing.

The rocks fell from the other side of the chasm about 20 metres away and crashed down onto this wet path in terrifyingly picturesque Taroko Gorge here in the north east of tiny Taiwan.

I shift my footing nervously.

A few minutes earlier further down the trail she had told me about the flooding. Sometimes this river, rushing green and foamy beneath us, will rise.

“Oh,” I say with the naivety that weariness and oppressive Nature can induce. “Up to how high?”

“There,” she says, pointing to a line of sticks and debris which is obviously a high water mark. It is half a dozen metres above us.

Despite the brochure beauties of Taroko Gorge this is becoming a disconcerting day. The reason I haven’t been able to drive across the centre of the island to the much postcarded honeymoon destination of Sun Moon Lake is because of typhoon rains and flooding in the hills which will, presumably, come sluicing through here any second now.

But no matter, because we are striding it out again, me following in the wake of this jackrabbit guide. She has given up being a doctor in Taipei to work in this beautiful mountain reserve where, for me, one glimpse of a wispy cloud coiled around a distant temple explains more about Chinese art than the many lectures I once endured.

Her refrain, repeated with minor variants -- all equally unmusical -- during this bracing but unnerving hike through Taroko is, “No like Taipei, too busy I think, maybe.”

I hadn’t need much encouragement to leave Taipei either: a million motor scooters, yellow dust blowing in from China, sometimes unbearable heat, and a haze that can prevent you from seeing more than a city block if you are two flights up.

There was the deafening internet café where I went to file stories amidst kids playing on-line crush‘n‘kill games, the mass of tourists around Snake Alley where some try the snake wine “for virility“, the sickly plum wine …

I had been drawn to Taiwan by its politics. Not particularly by the on-going dispute with mainland China or the thrilling thought that during my fortnight there I could be caught in some international shooting match. Or a typhoon.

Nope, I liked the idea that the longstanding Kuomintang (KMT) party had been dumped from office after a 50 year rule.

The KMT was one of the world’s richest political parties, had strong affiliations with the edgy military, and had built up assets of around $5.5 billion which include newspapers and radio stations, real estate, tourism enterprises, a movie company, insurance interests, and real estate throughout Asia, Australia, and in parts of Africa and the United States.

These boys were rich but, with the election of the Democratic People’s Party they were no longer politically powerful.

They were still enormously influential however.

“Black gold” -- the local shorthand for corruption money -- had poured in and out of the KMT’s coffers for decades and, despite the new premier Chang’s best efforts to reign it in, it was ingrained at all levels in Taiwan.

The former speaker of the Legislative Yuan -- one of the arms of Taiwan’s complex political structure -- had allegedly taken kick-backs of around $11 million which he used to solicit votes in his contest for the speakership. He was quoted as saying, “If I hadn’t gotten involved in politics I wouldn’t be in so much trouble.”

Taiwan -- under a new regime grappling with such high scale corruption -- sounded an interesting place. I just wondered how I might broach the subject of black gold delicately when I met someone senior from the Kuomintang.

I needn’t have worried.

Jonathan Shih of the KMT -- who previously worked for the multinational media outfit Knight-Ridder and got his MBA in the States -- presents his card and we sit down to talk.

I have just come from the DPP office, cramped and rented rooms across town, so it’s nice to be able to stretch out here, a dozen floors above Taipei in a spacious office as befit’s the director of KMT international relations. Put bluntly, Mr Shih is his party’s media spin-doctor for visiting journalists.

“Now yes, you want to talk about corruption then,” he starts.

And for the following 20 minutes tells me how it is being rooted out at all levels of the party. The party has also promised to stay away from the stock and real estate markets.

He is a pleasant man who laughs a lot while saying this. When we part he gives me a gift, a bloody great piece of production-line pottery which later than night I will auction off in my filthy, cockroach-ridden hostel.

Three days before, on arriving in Taipei, I have been taken by my gracious government hostess to an impressive hotel. I am travelling on a limited budget and this is well out of my league.

After I have settled in to my suite she rings to ask if everything is all right.

I say it is, but explain politely I need to find a cheaper hotel.

She calls back with a couple of cheaper options. But they too are still going to bust my budget.

She calls again with the rates at the YMCA, but even that is a little pricey. It is getting late and she, more used to dealing with moneyed diplomats, is becoming concerned.

My embarrassment for us both is creeping up, so I suggest I will find a place myself tomorrow and call her in the late afternoon. And I do.

Mrs Lin Tai Tai says she might not be around when I arrive at her Formosa Hostel, but just to let myself in.

I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for.

The Formosa Hostel is in an untidy lane off central Chungshan Road and a kindly gentleman in the corner coffee shop points me down the alley and indicates, through a hacking cough, that the Formosa Hostel is one of those rundown buildings to the right, the ones covered in loose wires hanging from the askew telephone poles.

I climb the narrow, dark stairwell between bicycles and boxes and two flights up meet a young English couple who are sitting on the steps smoking roll-your-owns.

Mrs Lin isn’t around, they confirm, but will be back later.

I sit and chat with them. They are in Taipei teaching English illegally to whomever wants lessons, and surly girl says she is slipping off to Bangkok tomorrow for a few days so she can get another two month tourist visa for Taiwan when she returns. They are broke like everyone at the Formosa Hostel, he says, shoving his butt into the flowerpot which is a graveyard of fag ends.

“Everyone here is teaching English illegally,” he says, then asks what I am doing in Taipei.

“I’m here to interview the premier.”

The Formosa Hostel is a dump. There are old couches, a dark and primitive cooking area in one corner, and a sagging shelf of books abandoned by former guests, most in oddly guttural European languages. Among the residents is a middle-aged, balding, overweight American called Raymond whom I never see in anything other than his stained Y-fronts in the week I am there. There are also two crisp Swedes who keep shutting the windows we open to let the smells out.

Every night we all chat about our day or watch the ancient television, and try not to glance at Raymond’s saggy crotch.

But my room is adequate.

Through a dorm which sleeps six in bunk beds of concentration camp-like comfort is a doorway which opens onto another room. It holds a bunk and, best of all for my purposes, a small desk.

Mrs Lin, who has turned up to proudly give me the conducted tour, beams when I say I will take it. I pay in advance for the week and it costs about the same as my first night in the more expensive place.

Mrs Lin, who has turned up to proudly give me the conducted tour, beams when I say I will take it. I pay in advance for the week and it costs about the same as my first night in the more expensive place.

A leaking air conditioning unit blocks out all light through my tiny window, there are a few large and not even vaguely nervous cockroaches, and mattresses which betray the occupancy of previous incontinents and honeymooners.

It is a perfect firetrap -- but dirt cheap and conveniently located. At the end of the lane directly opposite on Chungshan is the upmarket Ambassador Hotel.

I call my minder and say that is where I will meet her tomorrow morning for the first of a round of interviews with various politicos and spin-merchants.

The following morning, groomed, with a pocket full of bilingual business cards and dressed in a dark suit, I meet her in the golden, chandelier-filled lobby of the Ambassador -- and so begins a game we play all week.

She is confused. I have moved out of the hotel she had booked me in to, yet I am now here at the nouveau-riche Ambassador?

“Oh no, I am staying at the Formosa Hostel,” I say, and she faithfully notes this down.

After a day of appointments with various KMT and DPP officials our driver drops us back at the Ambassador. We agree to meet in the lobby again the next morning for another suit-filled circuit where I frequently hear of Taiwan juggling progressive enterprise and technology with environmental concerns. This is “the green silicon island” I am told repeatedly.

The following morning she tells me she had rung the Formosa Hotel last night and was told I was not booked in there.

“No, not the Formosa Hotel. The Formosa Hostel,” I say.

Ahhh.

And our day of interviews begins, and again we arrive back at the Ambassador that evening, me carrying more gifts from my various meetings.

The following morning she says she had rung the Formosa Hostel and a strange man had answered who didn’t know if I was there.

“No, it is a small place and anyone answers the phone. But people can leave a message on the blackboard for me.”

She asks me no further questions that week.

Every night back at the hostel I display my gifts of the day and there is an auction for those which I cannot carry home.

Bids for an obese red vase or ugly fountain pen start at a plate of noodles and work up to a bottle of plum wine or some other unfamiliar alcoholic concoction from the nearby 7/11.

Later I grope my way through the dark bunkhouse to my small door, lock it behind me, write up my notes, then sink into a deep stupor between the filthy sheets and the family of roaches.

I never see Mrs Lin again during my stay.

Only Raymond in his saggy underpants.

A week of card-exchanging meetings later -- having also taken in the absurdly beautiful National Palace Museum filled with the traditional Chinese art brought over from the mainland half a century ago, the changing of the guard outside the Chiang Kaishek Memorial (choreographed by the Ministry of Silly Walks), a delightful piano concert in the Sun Yatsen Memorial Hall and evenings in the incense-filled Lungshan Temple -- it is time to leave Taipei.

I tell my minder I now intend to spend a week travelling around the country.

Already alarmed by my elusiveness she is now genuinely fearful.: How would I do this? How could I find a place to stay? What if I get lost? Please be careful.

I reassure her and confidently leave for the train station to head to Hualien on the east coast -- and with no effort at all catch the wrong train.

Later that night I arrive in the small town, find a room and the next day head out to Taroko Gorge nearby for stories of dead tourists and terrifying floods.

It is a lonely trip around the country: Taitung down the coast is unattractive and the “beach” held in place by blocks of cement; in Tainan I drift through a dozen more temples and spend the night with some students in a karaoke bar; in Taichung I take to my bed at noon while jets roar overhead. I have to turn up the volume to hear The Deerhunter.

During the week I see little evidence of the green silicon island, just people going about their light-industrial business and throwing rubbish out the back door.

Back in Taipei I ring my minder. She is relieved I have been safe (“You are a brave man”) and asks how I enjoyed myself. I faithfully lie, thank her for her patience and assistance, and head for the airport.

I have booked a flight to Seoul to have another poke around Korea and will be back in Taipei in week to catch a connecting flight home.

Or maybe not.

I had arrived in Taiwan on a visa-free fortnight visit. I am leaving after 14 days, plus 12 hours.

The customs men are helpful and laugh about me unintentionally overstaying. So I pay my fine -- around $60 if I recall -- but then am stumped when they tell me, after the stamp had gone in my passport, that I am now prevented from returning to Taiwan for a year.

But I have to come back through here to get my flight back to New Zealand I whine.

Their previously serviceable English fails, my non-existent Chinese and heavy frowns are of no help.

Another customs agent is called, more discussion, the matter is resolved to their satisfaction: I should apply for a new visa in Seoul.

I do. It takes half a day, requires a new photograph and much filling out of forms.

“I’m going off the Taiwanese and their damnable bureaucracy,” I tell our Korean ambassador when I am an hour late for our lunch.

Arriving mid-morning back in Taiwan from Seoul I cannot be bothered making my way into scooter-littered Taipei. So I spend the day waiting for my evening flight in the new terminal. It is clean, deserted and utterly depressing.

I am feeling ambivalent about my trip to Taiwan: one part of me would trade the discomforts and high-powered meetings in favour of just staying at home; another part of me however has loved every minute of the politics, the inconveniences and even the Formosa Hostel.

I pass the dreary day reading singer Jimmy Buffet’s hilarious autobiography which I have picked up in Seoul. The man from Margaritaville tells stories of a footloose life, making music, flying his seaplane to South America, and reflects on a significant birthday.

Sitting in that soul-abusing, hygienic airport with its lonely rows of plastic seats it is a pleasant, even romantic, diversion. He closes his book with a poem by Don Blanding, a clumsy and obvious thing:

“How very simple life would be,

If only there were two of me.

A Restless Me to drift and roam

A Quiet Me to stay at home …”

Buffett’s book is called A Pirate Looks at 50. A week after I leave the silicon green island for the last time I will turn 50 myself. The “two of me“.

post a comment