Graham Reid | | 4 min read

One golden afternoon in August, coming back from the Arsenal district of Venice by vaporetto, I saw it looming up behind the beautiful church of Santa Maria della Salute: an enormous, gleaming white cruise ship perhaps 10-storeys high.

And in that moment, standing on the vaporetto with dozens of other tourists, I recognised the problem all around me.

Like the many millions who visit Venice every year, I felt I had a legitimate purpose. In this case to go, for the third time, to the Venice Biennale, a showcase of international art which has been running, off and on (war sometimes intervened), since 1895.

I would spend my money in restaurants and bars, pay around $240 a night for a modest but comfortable room with a shower and toilet down the hall, and buy some clothes.

With a clear conscience I could feel I was contributing to the local economy.

Tourists outnumber locals by an astonishing factor: according to the recent census, the resident population is fewer than 55,000 who try to live around, and with, the camera-clicking throng.

Venice groans under the weight of foreign feet, yet there have been plans to expand the port to accommodate more and bigger ships. The city has sunk more than 20cm in the past century, some areas greater than others, and that was before the real impact of global warming and the serious traffic from cruise ships.

Environmentalists say the port expansion, which will involve dredging and more huge cruising and cargo vessels in these fragile waters, is going to lead to a rise in the sea level of the lagoon.

Little wonder there is an organisation called Venice in Peril.

However writers rarely apply themselves to Venice as they would another city: they reflect and meditate on it; consider it through a prism; attempt to conjure up its magic in allusive prose which invariably fall short of a true picture.

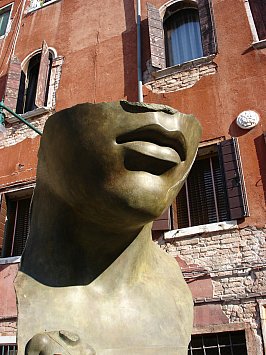

Artists and photographers offer similarly narrow views, many of them cliched to the point of tedium.

The frame writers and artists use can exclude the inconvenient reality.

The English writer Peter Ackroyd’s Venice: Pure City may be a poetically philosophical look at this marvellous city, but he too falls for accumulation of evocative phrases rather than dealing with the uncomfortable truth of the Venice we see today. He is all romantic foreplay.

In his tie-in television series his film crew manage the remarkable: images of Venice without people. Their close-focus Venice is graceful architecture, wistful nostalgia, and misty vistas. It is not the crowded streets around Rialto, shops selling Carnevale masks or the crass advertising which encroaches relentlessly.

The real Venice, the one becoming more like a theme park than a real city, barely gets mentioned. In passing Ackroyd notes the 20th and 21st centuries as if they are afterthoughts. But today a third of the population is over 60, and locals just keep leaving.

Beyond the attrition of its population through death and departure, Venice still grapples with flooding and rising waters.

It is now more than 40 years since the abnormal conjunction of a high tide, rivers swollen by rainfall and Sirocco winds filled the Lagoon and floodwaters rushed into the city.

Artworks valued at around $9 billion were damaged that day in November 1966, and Venetians were trapped in, or driven from, their homes.

The scale of the disaster, and it has happened since, meant something had to be done and so an ambitious scheme -- massive floodgates at the Malamocco inlet -- was mooted. However the Mose scheme, as it was called, fell prey to political indecision and protracted discussion.

Mose was expected to be functioning by 2011, then 2014. The cost has escalated accordingly.

Whether there will be many Venetians left in the city by the time it is done is another question.

“The more people leave, the more ordinary amenities like grocery shops and bakeries disappear with them,” wrote Independent journalist Peter Popham more than a decade ago, “making life more difficult for those who remain.

“Venetians are becoming strangers in their own home town.”

This is a refrain among writers -- such as John Berendt in his insightful The City of Falling Angels of 2005 -- who look at Venice as it is, not as it once was.

Demographers predict -- although this won’t happen -- if Venetians continue to leave their city at the current rate the last one will quit in about 20 years.

There have been funeral parades commemorating the death of the city. Some give it until 2100 before it sinks beneath the sea.

But tourists don’t care and will continue to go to beautiful Venice, and in even bigger cruise ships.

It is dilemma and, as I realised when I saw that floating hotel coming in, there is no easy solution.

In truth, I am the problem.

.

These entries are of little consequence to anyone other than me Graham Reid, the author of this site, and maybe my family, researchers and those with too much time on their hands.

Enjoy these random oddities at Personal Elsewhere.

post a comment