Graham Reid | | 6 min read

I've been lucky when I've travelled: I've never lost luggage, only once missed a flight (but salvaged a funny story out of it), have been held up at Customs frequently but again, funny stories. I've never been seriously confronted by a gun or a knife.

Not that I didn't go to some dodgy places: I'd only walked a block in New Orleans when I realised I was the wrong colour in the wrong district. And there were uneasy times in parts of New York at night before the monied displaced the damaged.

The Solomon Islands in 2002 was an edgy place. I arrived the day after someone had stepped out of the bushes and taken a shot at the prime minister's senior advisor.

I was there with the Herald photographer Alan for two weeks in a gap after a period of killings and political unrest. My job was to take the temperature of what was happening in the Solomons and explain it to readers of the New Zealand Herald.

On the island of Malaita a mad and explosive guy wanted the camera. Since the fighting began the warders at the mental hospital had fled and the patients like him had been let out.

Later that day we were having drinks with some young guys and one got very drunk and – given machetes were close to hand – it looked serious. Deadly serious.

They were unexpected incidents, but I only had myself to blame for going past White River outside Honiara. I'd been warned that White River was as far as you could go in safety at that time because after that you were in the territory of the unpredictable rebel boys.

So I got on the local bus and went to White River.

So I got on the local bus and went to White River.

I got off and went across the bridge where there was a pathetic little market, just half a dozen tables where women sold a few paltry fruits and root vegetables.

I loitered around, talked to a couple of old guys – pidgin was pretty easy to understand – then suddenly a flatbed track roared up with half a dozen angry-looking young guys carrying the familiar bamboo sticks just like the ones I was caned with at school.

There were machetes too.

They sized me up from a distance then came my way. By the time they circled me I was back on the bridge – naively believing that once I crossed they wouldn't follow.

But I was hemmed in.

I don't smoke but in certain places carry cigarettes as a kind of currency.

I don't smoke but in certain places carry cigarettes as a kind of currency.

So as I stood there looking at the muddy stream below I casually pulled out a cigarette and asked in anyone had a light. As one of them shuffled in a pocket I offered the smokes around and for a few minutes we stood there in smoky silence. They were impossible to read behind their wrap-around shades.

But in Honiara I'd found that when I spoke with gangs of young men they were more menacing in appearance than reality. And the minute Alan appeared with a camera they would pose with wide smiles and flash peace signs.

These guys at White River weren't like that but as they watched I eased my way past a couple of them and started to walk slowly away. There was some name calling and the air was cracked a couple of times by the bamboo canes. I kept on walking.

I never looked back and the following day I heard there had been “an incident” down there where someone was slashed.

A more terrifying and visceral experience came in an unexpected place closer to home and around the same time.

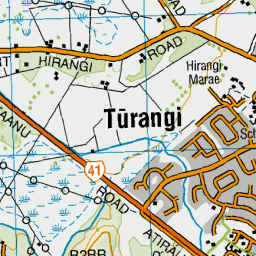

The Herald wanted a story on the small town of Turangi on the shores of Lake Taupo in the centre of New Zealand's North Island.

It was a town within striking distance of the ski fields, right next to excellent lake and trout fishing rivers. It seemed to have enormous potential but was troubled and dying. My job was to spend a couple of days there, ask questions and find out why.

The first place I went was the local pub.

The first place I went was the local pub.

It was morning and there were a lot of people at the pokies already.

I met a local cop who explained the town was the nearest to two prisons so there was a constant influx of families who came down for a few months or so to be near mum or dad or whomever was inside. These people had no attachment to the town, the kids didn't bother with school and just got into trouble. At night all the shops pulled their roller-doors down.

It was grim.

I met with members of the local iwi who were optimistic and had plans but little money, I went to an impressive new bar-cum-restaurant a little further round the lake which had a great view, nice ambience and no customers.

It was suggested by one of the iwi members whom I'd met in the local hotel that I pop back to the bar later that night to get a feel for the locals and have a chat with people.

After dinner in a deserted restaurant I drove back past the shopping area, deserted except for a few kids on bikes banging on the roller-doors, and went to the pub. It was late, probably past official closing time, but the place was a blaze of lights and laughter.

I went in – the only pakeha (non-Maori) in the place I would think – and nodded at various people.

It was a rough pub: gang members, men and women almost comatose from the booze and whatever, laughter and angry shouts . . .

It was a rough pub: gang members, men and women almost comatose from the booze and whatever, laughter and angry shouts . . .

I chatted with a couple of guys who were curious about who I was: years before I'd learned never to chat to women in such bars, there's always some jealous or possessive guy nearby.

I managed to pass an uncomfortable 15 minutes or so before I even got to the bar for a drink.

I stood next to a huge, well-muscled Maori gang member who immediately told me he was drinking “topshelfs”: a shot of each spirit on the top shelf – gin, rum, whisky and whatever else – in a glass with some Coke.

I'd always thought it was illegal to serve. This guy looked like most things he did or demanded were illegal.

He told me he was “just out of Parry” – Paremoremo maximum security prison – and had come down here because he had a mate in the prison nearby.

Within minutes he was steaming with anger and boiling rage, telling me how when he was inside he – I'm editing and polishing his words here – stabbed some guy in the neck with a toothbrush he'd sharpened.

Before I had time to think about that he jumped up grabbed me in a headlock and lifted me off the ground, shoving his fist into my neck repeatedly as I struggled to breathe.

“Like that! Like that!” he shouted.

After what seemed like gasping minutes, he loosed his grip and shoved me back against the bar.

That was how they did in Parry, apparently.

The bar behind me was in an uproar: some wanted to intervene when they saw what was happening, others were urging him on, most just shouting and hooting.

I didn't finish my drink but after a few discreet minutes turned and walked straight to the door, down the hall and out to the car.

Inside the bar I could hear a sudden crashing of glass and what I took to be upturning of a table, screams and more shouting.

I drove back to the motel and waiting for morning when I could get out of town.

That was many years ago and I'm sure Turangi is a much nicer place.

That was many years ago and I'm sure Turangi is a much nicer place.

But I left, waving to the local cop who was standing outside the police station, and got back on the highway which goes right past Turangi and headed back up north.

I had my story – that incident not included – and have never felt the need to go back to Turangi, or White River for that matter, since.

.

These entries are of little consequence to anyone other than me Graham Reid, the author of this site, and maybe my family, researchers and those with too much time on their hands.

Enjoy these random oddities at Personal Elsewhere.

Peggy in America - Jan 22, 2024

They're important to me. Even more so, that you can print them. It's more inter-national than we know, here in America. You are a constant bridge, to me. And not just by music; thank you for your fam-stories, and for (now?!) puttin' em out there for the rest of the world, as well.

SaveSome of us do, listen.

Good show, mate!!

P in A

post a comment