Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The drums tickle a beat into life, the dark drop of a bass builds and the guitars lock in to the distinctive rhythm, and as if by magic the reggae groove emerges. Heads nod, bodies move, and there is a spirit of joy and consciousness moving through the audience.

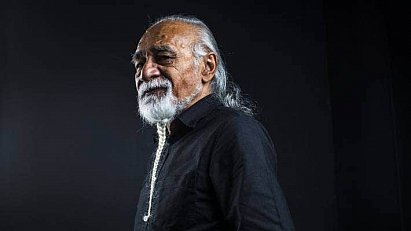

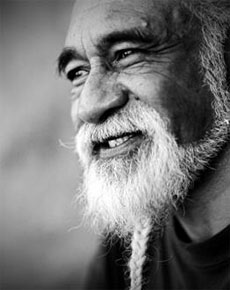

The music comes from Unity Pacific, one of New Zealand’s finest reggae bands, and upfront is the imposing and commanding figure of singer Tigi Ness, dreadlocked and imbued with the spirit of his Rastafarian faith as he sings of harmony, prophecy and faith.

The songs of Unity Pacific reach deep into the soul of listeners, and the reggae groove connects with the head and heart as if it simply rekindling a feeling that has always been there, waiting to be ignited again.

And in a way it has.

Since the earliest Bob Marley albums seeped into local consciousness, roots reggae and its many offshoots have been a consistent thread in the music of New Zealand/Aotearoa.

Some might go back to the mid 60s and note the Dinah Lee hit single Do the Blue Beat with its ska-kick rhythm, but certainly from the late Seventies/early Eighties local musicians picked up the reggae style and developed it into something unique.

Groups such as Herbs, Aotearoa, Dread Beat and Blood, and many others recorded and toured widely, and reggae became the musical pulse of the heartland. Rock bands like the Hallelujah Picassos adopted deep reggae, and when hip-hop arrived reggae was found there too in the music of artists such as the Upper Hutt Posse and Che Fu. Then there was the dub-heavy scene that developed in Wellington in the past decade, and the recent chart success of Katchafire.

Groups such as Herbs, Aotearoa, Dread Beat and Blood, and many others recorded and toured widely, and reggae became the musical pulse of the heartland. Rock bands like the Hallelujah Picassos adopted deep reggae, and when hip-hop arrived reggae was found there too in the music of artists such as the Upper Hutt Posse and Che Fu. Then there was the dub-heavy scene that developed in Wellington in the past decade, and the recent chart success of Katchafire.

Reggae has always been there, rekindled by inspirational musicians.

It has been surprising therefore that one of the country’s most distinguished -- and dapper -- Rastafarian musicians has been so seldom recognised.

Tigi Ness -- father of Che Fu -- has played reggae for more years than most care to recall, but it was only in 2003 that with the band Unity Pacific did he release an album, From Street to Sky.

With songs drawn from all parts of his long and interesting life -- before he became a Rastafarian, Ness was a member of the radical Polynesian Panthers and active in anti-Springbok tour movement in ‘81 -- his album seemed, as noted in a New Zealand Herald interview with Ness, “like a compilation from a man who never released a record”.

If that album was a clearing house for Ness, the latest outing by Unity Pacific, Into the Dread, reaches deep into his Rastafarian faith in songs such as Seven Bells (from the second Psalm), King of Justice (about Jesus Christ) and A Poor Man (Saveth a City) which is a tribute to Brother Gad, the founder of the Twelve Tribes of Israel of which Ness was an early member.

A gentle man with a voracious appetite for books and learning, Ness sees reggae as a healing music and Rastafarianism as a faith which offers a moral code to live by.

Ness believes in peace, brotherhood and unity, and Into the Dread is filled with such messages -- but also stern warnings of the judgement to come.

The album’s title was originally scheduled as “the dark sayings of old” but reverted to its current name because it evokes multiple meanings: it celebrates Rastafarianism; addresses the challenging times in which we live; refers to the deep groove of roots reggae and conveys a sense of urgent militancy; is about the mystical journey of life; and also celebrates a sense of family and a close-knit creative community.

The album’s title was originally scheduled as “the dark sayings of old” but reverted to its current name because it evokes multiple meanings: it celebrates Rastafarianism; addresses the challenging times in which we live; refers to the deep groove of roots reggae and conveys a sense of urgent militancy; is about the mystical journey of life; and also celebrates a sense of family and a close-knit creative community.

Just how close-knit Unity Pacific are as a band is evident in how little time it took these friends and like-minded musicians to record the album -- just four nights in York St Studios in Auckland.

This is a band which is so dedicated to its purpose that the musicians could simply set up in a studio and record live, even after all its members had worked their day jobs.

Just one listen to the deep groove of the dub-influenced 14-minute title track -- where Teina Winau’s melodic bass lines hold down the pulse and Rob Halcrow’s chipping guitar adds unsettling mood swings -- affirms that this is a group which has an intuitive understanding of reggae, and of each other.

Elsewhere on the album Ness makes an emotional plea on the loping, groove-riding Unity, the slightly eerie 1000 Nights conjures up an air of ancient mystery, and everywhere the collective spirit of the band creates classic reggae music full of musical nuance and colour.

And as if to remind a younger and more troubled generation of their potential, Unity Pacific go back to the title track from that previous album to consider the changes Ness -- and his peers -- have gone through: “Born in the city, raised on the streets, the factory was my future . . . . Look at me now, I think I‘m going to make it.”

It is a song of optimism borne of faith and experience, and emblematic of the spirit of Into the Dread, an album that may sometimes speak in the manner of the Old Testament but lives entirely in the modern world.

Tigi Ness and Unity Pacific have a life-affirming message for these troubled times, and they set it to a deep, powerful and compelling reggae rhythm.

Feel it. Believe it.

.

Into the Dread by Unity Pacific is reviewed at Elsewhere here. There are other articles on Tigi Ness and UNity Pacific at Elsewhere starting here.

post a comment