Graham Reid | | 5 min read

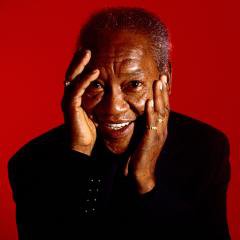

What becomes a legend most? In the case

of Ernest Ranglin, good humour and modesty.

This legend of Jamaican singlehandedly

created ska back in the Fifties; recorded the young Bob Marley;

arranged Millie Small’s international hit My Boy Lollipop in 64;

enjoyed a jazz career in London, New York and Florida; and in the

early-to-mid Nineties captured the ears of a new generation with his

reggae-jazz albums Memories of Barber Mack and Below the Bass Line.

And, always the musical explorer, he

released In Search of the Lost Riddim in the closing days of that

decade, which saw him playing alongside Senegalese guitarist Mansour

Seck and singer Baaba Maal in a marriage of West African and West

Indian sounds.

Yes, Ranglin is a genuine legend, has

been for decades, but catch him at home on this particular evening

and he’s got things other than music on his mind.

Yes, Ranglin is a genuine legend, has

been for decades, but catch him at home on this particular evening

and he’s got things other than music on his mind.

“I spent the day fixing the car,

tyres and the front end,” laughs this spry sounding 66 year old.

“You know the roads here are pretty bad.”

After decades on the jazz circuit

through Europe and the States, Ranglin returned to his beloved

Jamaica in 1990 for “peace and quiet, less rush. Wanna be more

relaxed, ya know?”

And has it been? He laughs again,

ignores mentioning the half-dozen albums he made in that time, the

concert tours and session dates, and says he doesn’t do as much as

he used to: “I'm a family man and you know what that’s like.

“I only play the concerts now but I

like to help guys out now and then,” he says.

It turns out he’s sitting in for a

young bassist in a local band who’s off to LA.

“And you know, it’s been a long

haul up the hill."

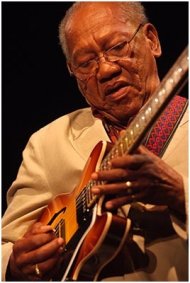

Ranglin’s career is too diverse to

readily encapsulate, but you could consider his recent reggae-jazz

pop albums as living testimony to the diversity of influences he

heard as a child, starting on ukelele then quickly outstripping his

guitar-playing uncles on their own instruments.

“I listened to the radio and heard

WINZ out of Miami and New Orleans stations. I was about 12 when I was

playing guitar and listening to Nat King Cole. I loved those good

grooves, and our own mento music - and calypso too which was

different from Trinidad’s. There was Latin American I heard and, of

course, all those great swing musicians like Duke Ellington and Count

Basie.

“After a while I heard rock’n’roll,

but I wasn’t much of a rock player. I admired it at first but was

more of a serious jazz player. Then I realised you can’t play one

type of music and survive so I tried my hand at everything. And I’ve

been trying until now.”

But out of that melange of influences –

and studio work with reggae and dub pioneers Clement "Coxsone" Dodd, Duke Reid,

Prince Buster and Lee Perry – Ranglin established himself as one of

the most in-demand players in the country.

But out of that melange of influences –

and studio work with reggae and dub pioneers Clement "Coxsone" Dodd, Duke Reid,

Prince Buster and Lee Perry – Ranglin established himself as one of

the most in-demand players in the country.

Then one Sunday in the studio, at the

prompting of Coxsone, he and Cluett Johnson started messing around

with shuffle rhythms. And, according to the history books, he

invented ska.

“I don’t think ‘I’ invented

it,” he says. “I think it should be ‘we.’ It was okay with

the musicians, up to a point, but there was also much improvement we

could make to the music.

“It’s never seen the opportunity to

be taken further. The producers kept down the progress of the music

because they wanted to keep one other type going and we could have

carried ska further.”

That said, the first wave of ska, which

picked up a young Marley along the way for whom Ranglin recorded It

Hurts To Be In Love, lasted from 1959 until shortly after Millie

Small’s chart-topper My Boy Lollipop in '64.

That year he sat in one night at Ronnie

Scott’s jazz club in London, out-smarted the band which thought he

was just some no-talent West Indian, and scored a nine-month

residency during which time Melody Maker voted him best new star in

their annual jazz poll.

By then rock steady, then reggae, had

taken over from ska: “I think because the climate we have here is

not like in England. Rock steady was slower and warmer, but in

England you needed something a little more brisk to keep the

circulation going.”

His laughter stops and he becomes

almost reverential when talking about the young Marley. Even then, he

says you could see in him the greatness to come.

“Instinct would tell you that,

something in the way he conducted himself and the way he would

rehearse with his band, the effort and concentration would tell you

this was the making of a great guy.”

During those crucial years of the late

Seventies when reggae enjoyed its greatest popularity, Ranglin toured

with Jimmy Cliff, then based himself in New York and later Fort

Lauderdale in Florida playing jazz. He recorded with pianists Monty

Alexander (with whom he was reunited for Below the Bass Line) and

Randy Weston.

Yet despite his fluid style, his

schooling in the great jazz traditions and the clear influence of his

early hero Charlie Christian in some of his playing, Ranglin seems a

marginal figure in jazz who is seldom mentioned in jazz

discographies. No matter, his recent albums have brought him a new

and more hip young audience and he sounds almost embarrassed about

having fans a third his age.

“You know, I don’t listen to much

music these days, it all goes in too many different directions. I

just sit around and watch and hope I have the ability to keep up. I

used to play every night in hotels and record, but now I just ease up

a little.

“Today is a different era, but to

know that people in it, young people, are listening to my music

well, it’s just great. I can’t think of anything else to think

about that. It’s just a great thing.

“Maybe I’m doing something right. Do you think?"

post a comment