Graham Reid | | 4 min read

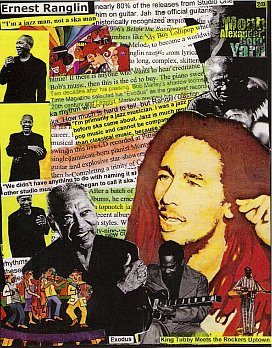

Ernest Ranglin and Monty Alexander: Redemption Song (2004)

Twenty years after the death of its

high priest, reggae still informed the vocabulary of music. Reggae

had so thoroughly infiltrated pop, rock, hip hop and electronica, we

hardly noticed it any more. Still don't.

And if it isn’t in the music itself –

the bass lines, off-accent drumming, choppy guitars – then it's in

the attitude reggae producers such as Lee Perry, King Tubby, Clement Dodd and

others brought to what was possible in a studio. Yes, Bob Marley may be gone

-- and Peter and so many more -- but the musical message they brought

lives on everywhere.

Well, almost everywhere.

No one seriously expects classical

musicians to explore reggae riddum (although there’s no reason why

they shouldn’t and the Reggae Philharmonic Orchestra had a decent stab at it) and jazz was particularly tardy in tuning in.

Certainly down the years there were jazz musicians who tuned to

reggae, most notably sax player Oliver Lake who in 1978 (around the

time of Bob's Kaya) recorded the track Change One, which had an

unmistakable Caribbean influence.

Lake, who co-founded the Black Artists

Group in St Louis in 1968 after being inspired by Chicago’s AACM,

always had an interest in Caribbean music, but a trip around the

islands in '80 confirmed for him there was a rhythmic pulse worth

delving into seriously.

He formed Jump Up, a lively jazz-dance

band which took off into reggae and back-to-Africa styles. Throughout

the early and mid Eighties, Jump Up (in vibrant multi-coloured stage

outfits in the manner off the Art Ensemble of Chicago) were something

of a sensation and even now their self-titled debut and Plug It

albums are worth tracking down.

However Lake also played in the World

Saxophone Quartet and other projects which became more successful so

Jump Up withered and faded.

Bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma also

explored reggae around the same time and UK saxophonist Courtney

Pine, who grew up on the stuff, always used it as a springboard.

There have been others too -- London’s

Jazz Jamaica was more JA-UK-MOR than jazz however – but

surprisingly few.

Most visible has always been guitarist

Ernest Ranglin, the man many say invented ska in Coxsone Dodds'

Jamaican studio in the late Fifties.

In '59 Ernest Ranglin recorded the young Bob

Marley, but his most visible ska hit was My Boy Lollipop with Millie

Small in '64.

Ranglin told me ska never had the

opportunity to be taken further because the producers wanted to keep

hits coming by not messing with the choppy, addictive formula. So he

headed to London and Ronnie Scott’s jazz club, and to this day

insists he is a jazz musician, but one with a foot in reggae. He

toured with Jimmy Cliff in the Seventies and latterly recorded

excellent reggae-conscious jazz albums: Below the Bassline from '97

featured pianist Monty Alexander and Memories of Barber Mack from the

following year had Sly Dunbar on drums.

Ranglin has the reggae spirit within

him.

And so does Alexander, whose Goin' Yard

in '01 completed a trilogy of reggae-jazz recordings which began with

Stir it Up from '99 where he played Bob songs, and Monty Meets Sly

and Robbie. Alexander incorporates nyabinghi rhythms, melodica, the

breezy JA-vibe and fat-bottom bass into his jazz-reggae and never

sounds anything less than authentic, and unique.

Should any hardcore jazz head doubt

Alexander‘s credentials, we need only note the Jamaican-born

pianist also played with Milt Jackson, Dizzy Gillespie and Sonny

Rollins.

Goin’ Yard, recorded live in

Pittsburgh, is at its best when he dug into Augustus Pablo's King

Tubby Meets the Rockers Uptown, and creates epics out Marley's Could

You Be Loved and Exodus, the latter opening with him weaving into the

melody via the famous theme to the movie of the same name.

The material not drawn from reggae but

contemporary jazz sounds the best.

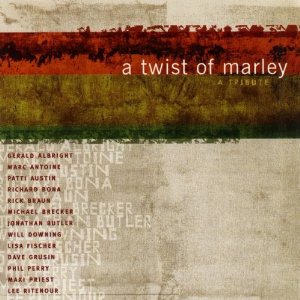

Around the same time as the engrossing

Goin' Yard was a jazz tribute to Bob under the appalling title, A

Twist of Marley (a cousin to A Nod to Bob, ie. Dylan).

It featured guitarist Lee Ritenour,

pianist Dave Grusin, trombonist Bill Reichenbach and vocalists Maxi

Priest, Lisa Fischer, Jonathan Butler and Phil Perry among others.

As expected with a tribute, it was

patchy (if I never hear the “r'n'b version” of Get Up Stand Up

again L’ll be happy) and Ritenour always makes albums with a high

Teflon factor. (See? Nothing sticks!)

There was some good stuff – Exodus is

hard to screw up and saxophonist Michael Brecker doesn't, and

trumpeter Rick Braun plays tough but sensitive mute work on So Much

Trouble – but overall you’d probably file it in your

under-explored “tribute” pile rather than the “reggae” or

“jazz” stacks which get repeat plays.

The odd thing in this jazz-reggae

however is just how readily Marley's music can be adapted.

The strength of his melodies, and the

memorable riffs he wrote (Jamming and Could You Be Loved are

recognisable from the first bar) can be bent to other purposes.

On the Twist album there’s a South

African treatment of Redemption Song by Richard Bona complete with SA

vocal chorus which is pretty damn nice. And Will Dowling – who

turned in an excellent treatment of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme at

the start of his career in the late Eighties – finds a well of late

night sweet soul feeling at the heart of Is This Love.

Polite as he was, Bob would have

doubtless been generous about the Twist of Marley album, but – without

wishing to second guess what the dead might have said as we never

should do -- you suspect he'd have passed on most of this tribute,

but would have delighted in Dowling's Is This Love.

David Sampson - Sep 3, 2015

Thanks for a great article Graham. Another fine reggae-jazz CD to remember is Reggaeology (on Rogueart in 2010) by the ridiculous line-up of Hamid Drake, Napoleon Maddox, Jeff Parker, Jeff Albert, Jeb Bishop and Josh Abrams

SaveCheers

post a comment