Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Concrete Jungle (Jamaican version)

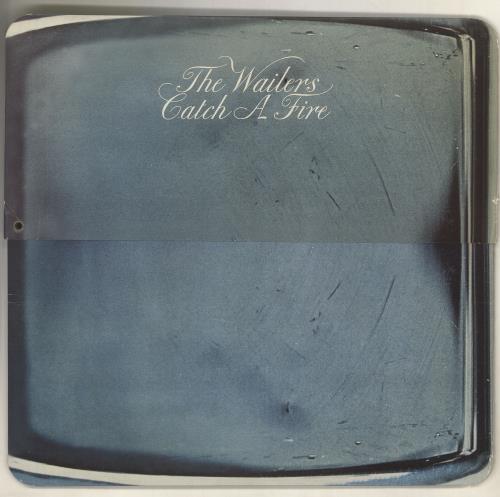

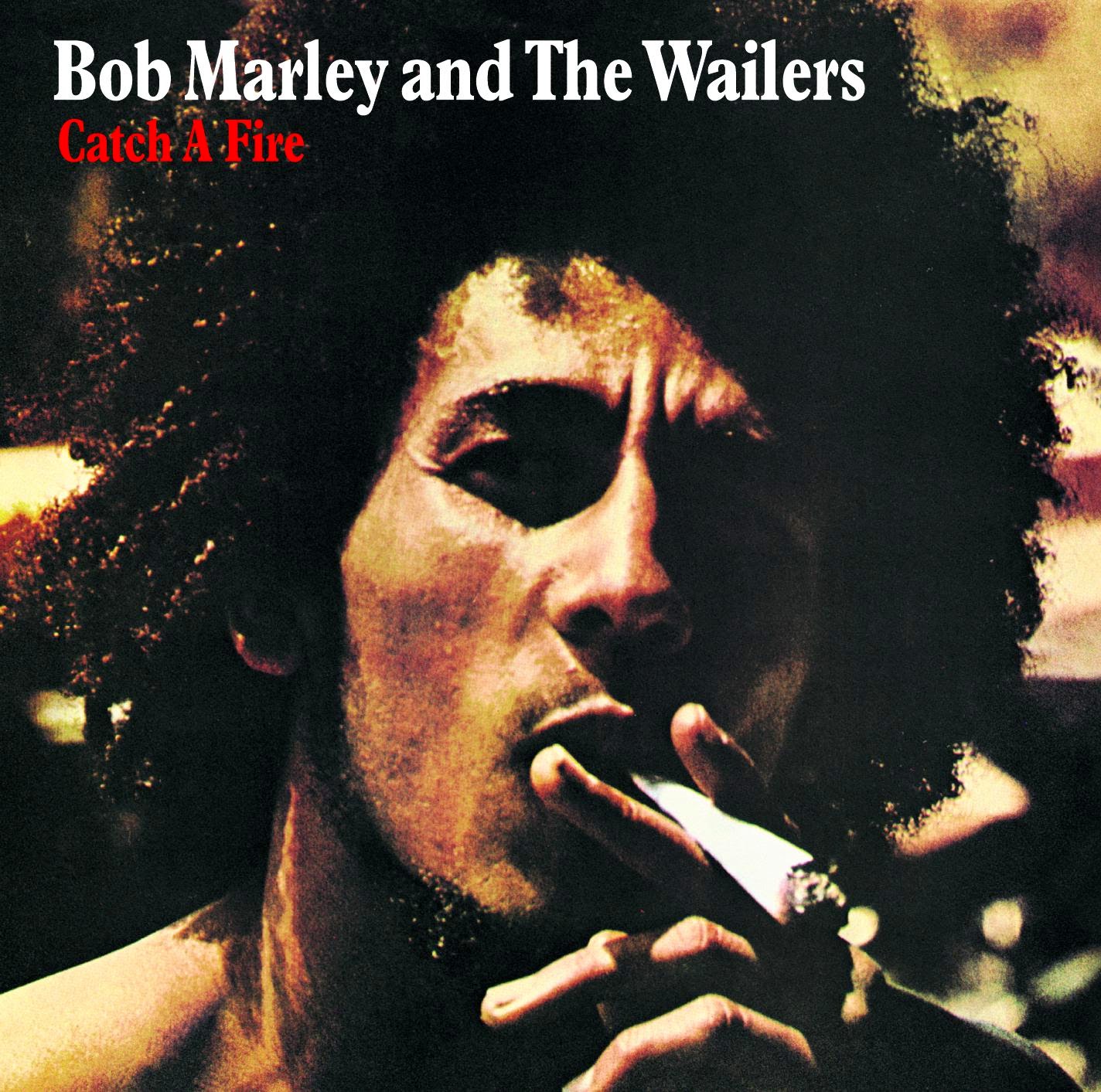

There are two versions of the Catch A Fire album of '73, and both are essential.

And the fact that each of these were made and released is a story in itself.

The second version – fine tweaked for the international market by Island Records' Chris Blackwell with Marley's approval – might not have sold in the numbers everyone concerned hoped for (#171 in the US, nothing in the UK) but it changed everything for reggae, Island and especially Marley and the Wailers.

Before Catch A Fire the market for reggae outside of Jamaica in the UK (beyond the diaspora) was just one-off singles (often gimmick songs) or albums which were uneven compilations in sometimes luridly sexist covers.

Catch A Fire was nothing like that.

It was a reggae album of distinctive tracks which flowed like any classic pop or rock album. You needed to hear the whole thing because moods and themes were cross-referenced.

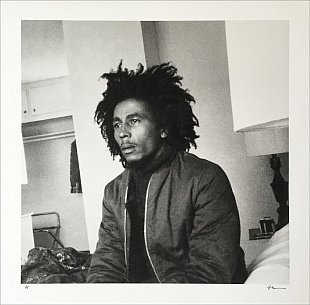

Reggae as an international sound, and Marley's journey to being the first Third World Superstar, began with this album.

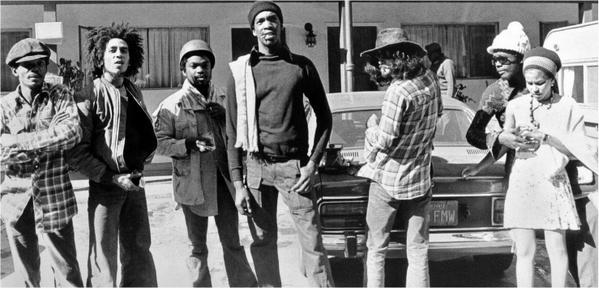

In 1972, Marley and the Wailers (which included longtime members Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston aka Bunny Wailer, and the Barrett brothers Aston and Carlton on bass and drums) were in Britain and broke after a failed tour with American singer Johnny Nash.

The Wailers' freelance manager/record company promo guy Brent Clarke approached Blackwell at the Island label – which had released the Wailers in the Sixties – with a view to getting a loan (and maybe an album project was mentioned).

At that time Blackwell hadn't met Marley but when he did he suggested they record an album back home in Jamaica.

At that time Blackwell hadn't met Marley but when he did he suggested they record an album back home in Jamaica.

Marley told Blackwell how much it would cost – it was ridiculously cheap – and Blackwell signed the cheque saying there would be a similar cheque on delivery. The band flew home.

“Everybody said I was crazy,” said Blackwell later, “that these were bad, unreliable guys who would rip me off and I'd never get my money back or see them again.”

What no one factored in was just how ambitious Marley and the Wailers were: they'd been jogging on the spot in Jamaica after a couple of successful early singles and albums produced by Coxsone Dodd (at Studio One) and Lee Perry (at Randy's Studio) hadn't made much of a dent, despite the strengths of the songs like Simmer Down (their huge local hit), Soul Rebel, Try Me, 400 Years, Duppy Conqueror, Kaya, Sun is Shining and others, some of which Marley would revisit in his subsequent career.

Marley by himself had endured a miserable time in Sweden with Nash before the Wailers came to the UK and was looking for a way out of almost a decade of frustration and being poor.

With little to lose and a lot to gain by the association with Blackwell's London-based label, Marley and the Wailers settled in at various studios in Kingston to record what would become their first defining moment.

Blackwell dropped by during the session for Slave Driver and was gob-smacked. This was the authentic Jamaican sound he wanted.

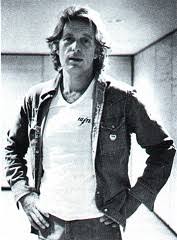

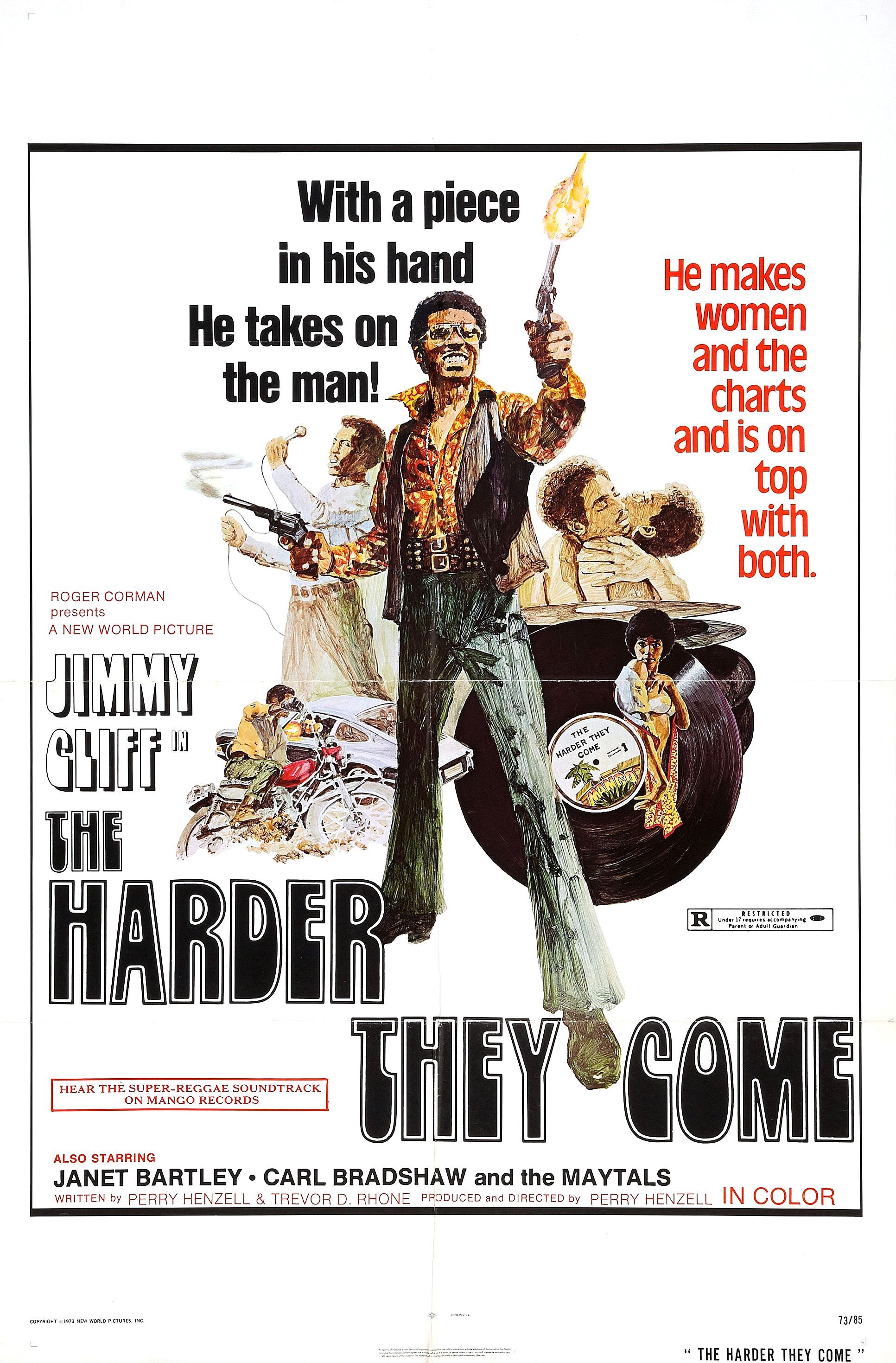

Blackwell had been looking for a singular artist who could do what he imagined, and had thought he'd found it in Jimmy Cliff who had just starred as the sassy street bandit in the film The Harder They Come, directed by Blackwell's childhood friend Perry Henzell.

Blackwell had been looking for a singular artist who could do what he imagined, and had thought he'd found it in Jimmy Cliff who had just starred as the sassy street bandit in the film The Harder They Come, directed by Blackwell's childhood friend Perry Henzell.

The film became a cult item but the soundtrack took off.

Blackwell was primed with Cliff, the Cliff announced he was quitting Island because he could get better money elsewhere and Blackwell was spending too much time on his rock acts like Traffic.

A week later Bob Marley walked in.

“He came in right at the time when there was this idea in my head that a rebel-type character could really emerge. And that I could break such an artist.

“I was dealing with rock music which was really rebel music. I felt that would really be the way to break Jamaican music.

“But you needed somebody who could be that image. When Bob walked in he really was that image.”

Blackwell knew Jamaica and the Rastafarians. As a teenager living there, when his boat had run aground he was rescued and cared for by Rastas where he saw the other side of these people considered mad and dangerous by most.

He saw in Marley something others had not, so signed the cheque.

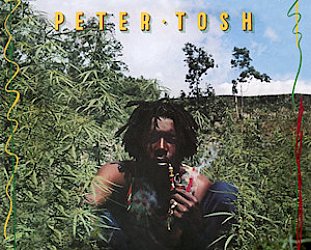

A few weeks later Marley was back in London with the master tapes of 11 songs, among them Concrete Jungle, Slave Driver and Stir It Up, and Tosh's Stop That Train and 400 Years. All songs which defined their spare, early sound.

A few weeks later Marley was back in London with the master tapes of 11 songs, among them Concrete Jungle, Slave Driver and Stir It Up, and Tosh's Stop That Train and 400 Years. All songs which defined their spare, early sound.

That was the first version of the album but, much as Blackwell loved it, he wanted to take it to that audience he suspected was out there. That meant some embellishment to be able to market more as a rock album than some speciality item.

In came Texan 'Rabbit' Bundrick on synths and keyboards (who Marley knew from being with Nash in Stockholm), guitarist Wayne Perkins from Muscle Shoals, Alabama (who had no idea what reggae was and could barely understand a word the Wailers said) and Sly'n'Robbie alongside the core band and backing vocalists Rita Marley and Marcia Griffiths (Judy Mowatt yet to arrive to complete the I-Threes).

And yet out of that seeming culture and musical clash came the exceptional second version of the album, the one Blackwell tried to take to the world. Or at least UK audiences.

He marketed it like a rock album (copies to tastemakers) and wrapped it in a Zippo lighter fold-up cover (which proved too expensive so subsequent issues were more plainly packaged).

Two decades ago a deluxe double CD edition album of Catch A Fire appeared (it is all on Spotify) and it allowed us to hear the original Jamaican sound as well as the British revision.

Two decades ago a deluxe double CD edition album of Catch A Fire appeared (it is all on Spotify) and it allowed us to hear the original Jamaican sound as well as the British revision.

The original is terrific.

The sound is sparse, clear and direct. Marley is right there up front and his natural soulful voice comes through with a rare clarity over the choppy rhythm guitar and bass'n'drum team of the Barretts.

But what the album confirms is Blackwell's belief in Marley songwriting. He is the lover (Stir It Up, Baby We Got a Date, All Day All Night), the ghetto youth (Concrete Jungle) and a militant (Slave Driver). Add those songs and others to Peter Tosh's spiritually inclined Stop That Train and his yearning 400 Years (of slavery) and you had an album with the depth and breadth of the best rock albums.

A rarity in reggae at the time.

And -- in truth at the time of prog-rock, glam and hard rock -- rare enough in rock.

Trimmed of two songs (All Day All Night, No More Trouble), the running order changed to put the spirituality up front and with the smart embellishments by the ring-in musicians – notably Perkins' clever guitar fills and Bundrick's soulful organ – the second version of the album is smoother and, we might as well acknowledge, more directed at radio.

The scratchy reggae rhythm seems more prominent in songs like Slave Driver at the expense of the vocals. And Blackwell shoved the Rasta apocalypse and more problematic Midnight Ravers to the end: “Can't tell the woman from the man, they're dressed in the same pollution . . . their mind is confused with confusion . . .”

Either way however, the two versions of this album – different though they may be – are essential listening.

But if this was the album to take Bob Marley and the Wailers to a British audience, it didn't happen.

Appearances for a John Peel session and wonderful low-key Concrete Jungle and Stir It Up on The Old Grey Whistle Test TV show certainly got them visibility and the groundwork was laid for Burnin' the following year (the final album with Marley, Tosh and Bunny)

Certainly Eric Clapton's version of I Shot the Sheriff after Burnin' didn't hurt.

But if you are looking at a pivotal point between tough-slog Jamaica and global stardom it is Catch A Fire, no matter which version you hear.

But that original recording is the one.

.

You can hear both versions of Catch A Fire on Spotify here

For much more about Bob Marley at Elsewhere start here

.

post a comment