Graham Reid | | 6 min read

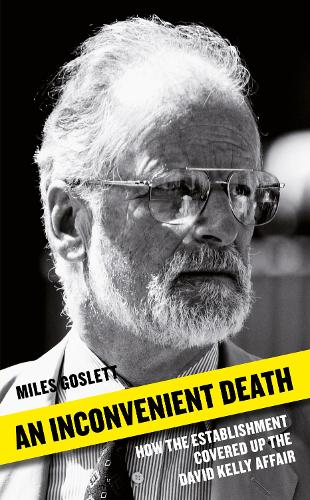

On a warm Thursday afternoon a little more than a month ago, a man in a white cotton shirt, jeans and brown shoes set off for a walk from his 18th-century farmhouse near the border of Oxfordshire and Wiltshire and never returned.

By his suicide that day the modest, quietly spoken Dr David Kelly, one of Britain's leading experts in biological and chemical weapons, became the unlikely flint sparking a flaming fight between Tony Blair's Government and the venerable institution of the BBC.

Without his tragic death many questions about the Blair Government's reasons for committing troops to an invasion of Iraq might never have been subject to a public examination.

Kelly allegedly told Gilligan that a Blair Government dossier last September had been changed to justify the invasion of Iraq.

"Sexed up" is the common parlance, a phrase attributed to Blair's communications chief, Alastair Campbell.

Gilligan broadcast the allegation on May 29 and Blair's inner circle, notably Campbell - an abrasive, hard-nosed, much derided former tabloid journalist usually described as the Labour Government's chief spin doctor - responded with angry denunciations and denials.

The inquiry into Kelly's death, overseen by Lord Hutton, is now in full swing, with Blair himself due to appear next week. The raw facts are already known - a packet of sleeping pills and a self-inflicted slash across Kelly's left wrist - but the inquiry was never going to be that simple.

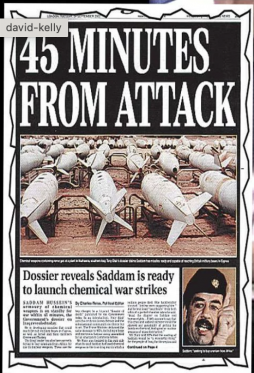

The issue was always going to be whether the Government manipulated what should have been objective data into a justification for an unpopular war, especially Blair's claim that Saddam Hussain had the capacity to launch weapons of mass destruction in 45 minutes.

Former British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook - who resigned over his Government's involvement in the invasion of Iraq - noted Hutton had been asked to do the impossible: to investigate Kelly's death while being warned off looking into events - such as that "sexed up" dossier - which led to the invasion.

"It would take the judgment of Solomon and the skills of a precision engineer to keep these two lines of inquiry in separate components," wrote Cook in the Independent.

After the first week, just 10 days ago, the counsel for the inquiry, James Dingleman, QC, had, with forensic accuracy and meticulous questions, drawn out previously undisclosed documents into how the controversial dossier had been assembled.

After the first week, just 10 days ago, the counsel for the inquiry, James Dingleman, QC, had, with forensic accuracy and meticulous questions, drawn out previously undisclosed documents into how the controversial dossier had been assembled.

Already, however, digressions have complicated the issue and the public has tuned out significantly. The inquiry has, inevitably perhaps, descended to a confusing melange of obfuscation and lies, claim and counter-claim, and dates and internal memos between faceless bureaucrats.

For the casual reader there have been too many names, too many contradictory statements, too much to follow. Other news - bombs in Jerusalem and Baghdad, something about the Beckhams - is much more eye-engaging and easier to follow.

But the inquiry has produced its share of insights into the machinations of Blair's Government - Campbell's diary entries and emails from Government sources have shown a Government keen to clamp down on Kelly and the BBC.

"This is now a game of chicken with the Beeb," wrote Blair's official spokesman Tom Kelly to Blair's chief of staff Jonathan Powell. "The only way they will shift is if they see the screws tightening."

Some have suggested that if the Government's poll ratings had been higher the report might simply have been denied and dismissed. But Labour's lead over the Conservatives was at its lowest ever after the story broke, and 34 per cent of the public said they were less likely to trust Blair on other matters because of the weapons row.

Blair's Government - surprisingly for a team famous for spin - felt personally affronted by the accusations of something less than integrity and needed a public rebuttal. And that's where the unfortunate Kelly came in.

But the portly Gilligan has proven to be no heroic barricade-storming journalist, and doubts have been raised about the accuracy of his report.

Kelly confirmed meeting Gilligan in late May but disputed the contents of the Today programme report a week later which claimed the Government had inserted the infamous "45 minutes" claim into the dossier.

Journalist Nick Rufford, who interviewed Kelly a number of times over the years, told the inquiry: "He said, 'I talked to him about factual stuff, the rest is bullshit.' It's very strong language for Dr Kelly to use."

This week it emerged that Gilligan had tried to influence the foreign affairs committee by suggesting questions to the Liberal Democrats to throw Labour off his scent by broadening the issue and dragging Kelly further into his battle with the Government.

It has been noted by the chairman of the committee that it was unprecedented for a witness to seek to influence its proceedings.

But more damning was having to admit to the Hutton inquiry a crucial error in his first broadcast which would seem to let the Government off the hook.

In the first days Gilligan - who has lost 9.5kg in the past few weeks thanks to what he called "the Campbell Diet" - was forced to concede that although Kelly had told him the single source for the "45 minutes" claim was unreliable, that didn't necessarily mean the Blair Government knew it was wrong.

That quite stunning admission was compounded by the presentation of an internal BBC memo in which the editor of the Today programme had complained of the broadcast and said, "This was a good piece of journalism marred by flawed reporting. Our biggest millstone has been his loose use of language and lack of judgment".

But the Hutton inquiry has shown how keen Blair and his loyalists were to demonstrate a cause for war. This week previously unpublished official papers showed doubts in high levels of the Government that before publication of the dossier there were doubts Saddam presented a threat, "let alone an imminent threat".

That was even after Blair had ordered a substantial rewrite of the document and the issuing of an instruction that "there has to be real intelligence" in the material.

But this week Hutton gave the clearest direction yet where this investigation - ostensibly into the suicide of a leading British scientist - may be heading.

He observed that given the BBC had been forced to withdraw its most serious charge that the document had been sexed up, he wondered why the Government had found it necessary to pull Kelly into the public arena for a gruelling questioning.

The most senior civil servant at the Ministry of Defence and one of Blair's official spokesmen, Godric Smith, told the inquiry he heard Downing St was prepared to drop the feud with the BBC - until Kelly was outed as the source. Then the gloves were off. Sir Kevin Tebbit, the most senior civil servant at the ministry, told the inquiry that the investigation into Kelly should be stepped up.

"The implication was that he [Blair] did want something done about this individual coming forward."

If a trail can be made back to Blair which suggests he wanted Kelly ruthlessly run to earth, then it will have the hallmarks of a vindictive, self-serving politician prepared to crush a hapless and honest citizen.

Fingers started being pointed within Blair's inner sanctum, and Secretary of State Geoff Hoon is starting to look like the fall guy for putting the heat on Kelly.

As the inquiry enters its third week, cynics are already saying that once Hoon is sacrificed it will be business as usual for Blair's Government.

The longer the Hutton inquiry goes on, and the more complex it becomes, the better some will like it. It is in Labour's interests that the unflattering headlines become inside stories.

So far no one has come out well: the Government looks as if it over-reacted and was hounding Kelly, journalists and senior civil servants; Gilligan has had to backtrack on some of his assertions; the ministry has been characterised as abandoning Kelly after he was outed by people in their own ranks; and the scientist himself looks to have been naive and unworldly.

In the same email to John Scarlett of the Joint Intelligence Committee on September 17, in which Blair's chief of staff Powell noted Saddam had not demonstrated a motive to attack his neighbours, let alone the West, he also said, "The dossier is good and convincing for those who are prepared to be convinced."

There are already those who think the same will be said - regardless of the findings - of the Hutton inquiry.

One thing is certain, there will be no banner headline in a British tabloid which reads: "Result!"

post a comment