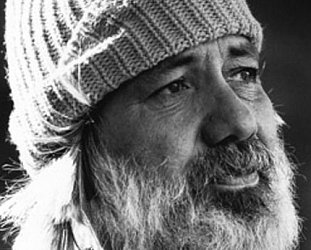

Graham Reid | | 10 min read

From this hilltop the mysterious, mute country across the river possesses a rugged beauty, its towering mountains crumpling to the far horizon, shimmering hazy blue in the heat.

Through powerful binoculars you can see farmers moving about their back-bending work in picturesque green rice paddies sculpted into hillsides. The river glints silver under the sun, your camera points towards unknown provinces ...

"No photographs," says the pistol-packing, impossibly young soldier as he patrols this military emplacement perched on a warm eerie above the border.

Up here you're in a nether world of razor wire, searchlights, and propaganda music blasting across the divide between these two countries, a flashpoint severed by a river where boats or fishermen are notably absent.

On the other side of the wire is the no-go of North Korea, a hermetically sealed country few visit and from which even fewer come. It is where propaganda passes for information and "the eternal president" Kim Il-sung has been dead for more than seven years.

The successor to "the Great Leader" has been his son Kim Jong-il - "the Dear Leader" - whose ascent to power was the first dynastic succession in a communist society. These are comrades from another planet.

North Korea - officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea - is a crucible of cryogenic Stalinism, a barbed wire bastion of hardline communism decades after the ideology has been discredited and abandoned elsewhere.

It permits only a few hundred tourists a year whose contact with local people is negligible. Travel is restricted and visitors are accompanied by a Government-employed tour guide at all times.

Here there's no Knowledge Wave, only suspicion, spying on your neighbour and shortages. Very few know anything of the outside world. "The fact is," says Roy Ferguson, New Zealand's ambassador on this side of the wire, "it is probably the most closed society in the world in terms of what the average person knows. I suspect the ruling elite is aware of what's happening in the world. We know chairman Kim reads the South Korean media and watches South Korean TV."

"The fact is," says Roy Ferguson, New Zealand's ambassador on this side of the wire, "it is probably the most closed society in the world in terms of what the average person knows. I suspect the ruling elite is aware of what's happening in the world. We know chairman Kim reads the South Korean media and watches South Korean TV."

Ferguson, a career diplomat, has been this country's ambassador to South Korea for two years and last week was appointed our first ambassador to the DPRK. Which means he'll soon go to the capital, P'yongyang, for the first time to present his credentials.

But why did New Zealand decide to officially recognise North Korea in March? They can't afford to buy anything and have nothing to sell. And it's falling apart.

Graham Kelly, Labour MP and chairperson of the Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade select committee who visited P'yongyang last month, described a place of unrelenting misery.

After years of floods in which half a million people lost their homes and closed the country's coal mines, there is a food deficit of two million tonnes. The economic infrastructure and social services have collapsed, power cuts are common and medicine is scarce.

You name it and North Korea doesn't have it. Or if it has, it's broken and there are no replacement parts.

Its archaic Soviet-subsidised nuclear power plants are crumbling with potentially Chernobyl-like consequences, and there's the fear they are armed to the eyeballs with nuclear weapons and angry enough to use them. Recognition, therefore, has less to do with trade than the bigger picture of stability in the region.

"Trade will be nominal, at best, at the moment," says Tony Browne, director of the north Asia division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. "We're part of an international consensus that the time has come to move from confrontation or isolation, and of trying to be more inclusionist."

In the 21st century North Korea is less a country than an anachronism, and our first ambassador there is 50-year-old Ferguson, who remains credited to the South in a symbolic gesture of support for the reunification of the Korean Peninsula.

Modest, moderate in his speech, and highly personable, Ferguson has had a diverse career in the diplomatic service.

His CV is impressive: an MA in history and political science from Canterbury University in 1973, a fellowship to the University of Pennsylvania where he graduated with an MA in international relations, joined Foreign Affairs in 1974, third secretary at the embassy in Manila for three years from 1976, first secretary at the High Commission in Canberra from 1982-86, and deputy head of the mission in Washington DC for five years until 1996. Between international postings he held various directorial positions in Wellington.

"Foreign Affairs is like having a number of different careers but all for the same employer," he says as he sits in his comfortable but hardly extravagant office 18 floors above the teeming streets of Seoul, the capital of South Korea. "Before here, I was director of personnel in the Foreign Ministry, a management job in Wellington with 600 employees, a budget of about $43 million and a division of 30 people. Here the job is totally different. That's what makes it so interesting."

"Before here, I was director of personnel in the Foreign Ministry, a management job in Wellington with 600 employees, a budget of about $43 million and a division of 30 people. Here the job is totally different. That's what makes it so interesting."

By his own admission he speaks little Korean ("of course going to meetings with substance I have an interpreter") but thoroughly enjoys the country. He mixes in diplomatic and cultural circles, and his wife Dawn has taught at the British School and lectured at Ehwa Women's University. They have two adult sons at university in New Zealand.

"Culturally [South] Korea is very rich, we've seen more orchestras and singers and ballets here in the last two years than in the previous 10. There's a very rich musical life, both traditional and Western music. We've seen the Bolshoi Ballet twice, they have lots of artists visiting here."

The culture compensates for the pollution, the yellow dust which blows across from the Gobi Desert, and the extremes of temperature. They get away with the Royal Asiatic Society on hiking trips and a fortnight ago holidayed in Mongolia, only three-and-a-half hours away.

The Fergusons' handsome home - full of original New Zealand artworks - is in the embassy district and this year comfortably hosted 100 servicemen who had served in the Korean War 50 years ago.

Of course it isn't all cucumber sandwiches and mountain climbing.

"The job is a combination of looking after New Zealand's economic and security interests. On the economic side [South] Korea is our fifth-largest export market, fifth-largest source of tourists and our third-largest source of foreign students. We have a huge economic relationship."

Ferguson also forges links between universities and tertiary institutions of both countries. During Helen Clark's visit this year, Seoul National University, the best in the country, signed a memorandum of intent with the University of Auckland to set up joint PhD programmes, "the first Seoul has ever done."

He battles away for access for new agriculture products (peaches, nectarines and other horticulture) and is constantly fighting to retain the access for those already granted such as deer velvet.

And in this country where people enjoy a tipple, has our man ever woken up after a night on the local firewater, soju, and sworn, "Never again"?

"That's more prevalent in commercial circles," he laughs. "I haven't had to drink for my country on too many occasions."

But always in the background is the volatile and highly armed North Korea.

Severed from the south by a 4km-wide Demilitarized Zone, North Korea is less than half the area of New Zealand. More than three-quarters of it is uninhabitable mountains. Its population of around 25 million (half that of the democratic South) is considered among the most ethnically homogeneous in the world. It's a Shangri-la under repressive socialism.

"You are aware of it," says Ferguson, "but life's very normal here. People have lived with it for so long now. We were very aware in June 99 when there was a naval incident in the West Sea. The North had been pushing over the line which demarcates the two with some fishing boats. The South warned them, there was an exchange of gunfire and some loss of life.

"An incident like that could expand into something much bigger if either side let it. We're confident the South isn't going to provoke or start a major war, but we know a lot less about the North."

L ast year there were encouraging signs the Democratic Peoples' Republic of Korea was moving away from its self-imposed seclusion. Chairman Kim and South Korea's Kim Dae-jung met at an historic summit in P'yongyang, and there were plans for rail and road links through the demilitarised zone. To outsiders it seemed the morally, politically and literally bankrupt regime was coming to an end. Browne, however, notes the Kim Government appears secure, "in large part to the extent it devotes resources to maintaining itself.

"The [summit] was a huge watershed in inter-Korean relations but hasn't been followed up. But since then Kim has been to Shanghai and Moscow so there is a prima facie assumption that at least there is some consideration being given to other systems, models and options."

When Ferguson presents his credentials he'll be asking what has happened to the assistance New Zealand has given through food aid programmes and Unicef. Since 1996 we've given $3.4 million of development aid, around $2 million of that to the Korean Energy Development Organisation which provides oil in return for stopping work on a nuclear plant producing weapons-grade nuclear material.

He may also raise the tetchy topic of human rights, although no one expects progress on anything to be rapid. Browne admits his discussions in P'yongyang last September when negotiating establishing this relationship were more a parallel monologue than a genuine dialogue.

Ferguson also won't see the depths of rural misery in the North, he'll be in P'yongyang, a modern city built since the Korean War and which Browne says is more attractive than Seoul. The Stalinist impact on the architecture is surprisingly light and "it has more of the feel of an East European city than a typical Asian one."

On this side of the wire South Korea is a high-energy construction site which now welcomes foreign investment ("I wouldn't have said that before 97," says Ferguson), is one of the most highly connected societies to the internet with great receptivity to e-commerce and which presents great business opportunities for New Zealand.

"There is more transparency in business, but still a way to go. I wouldn't want to paint an inaccurate picture of that," he says diplomatically.

Doing business anywhere in Asia requires patience, persistence and personal contact. If Ferguson has "a regular term" he could be back home in a year and the delicate negotiations and personal contact with the North will fall to someone else.

"I think that's what makes it a challenge and professionally exciting, you're blazing a trail. There aren't many places in the world we haven't had a diplomatic relationship and where people haven't been."

.

Note: In the mid Nineties I applied twice to visit North Korea and never received a response. When I mentioned this to someone from the Asia-New Zealand Foundation (now called Asia 2000 I think) he laughed and said there was no way I would be able to go. A few years previous I had written an unflattering piece about the country (in which I referred to its "cryogenically-frozen Stalinism") and my writing had been monitored ever since.

post a comment