Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Dick Raaijmakers: Tweeklank

When composer Douglas Lilburn left New Zealand at the dawn of the Sixties, it was because he felt he had been isolated from developments in contemporary music, and he was curious about electronic music.*

He was almost 50 when he left in '63 to travel to Hawaii, New York, Paris and England where he visited electronic studios, such as the BBC Radiophonic Studio in London, famous for producing the theme to the original Dr Who television series.

Returning from his sabbatical, he established the first electronic music studio in New Zealand at Victoria University and within three weeks submitted an electronic composition for a competition.

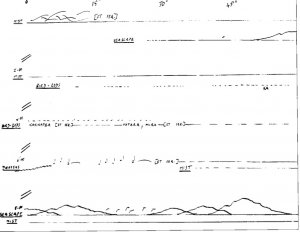

It was The Return, a 17 minute piece with a poem by Alistair Campbell and which utilised white noise (for mist), field recordings of the sea played at half speed, taped bird song slowed down . . .

However to be considered for the competition he also had to submit a score.

This is it (right).

This is it (right).

Most electronic music in written form looks like the page of a maths textbook, yet many composers -- Lilburn among them -- feel the possibilities of the instruments and technologies allow them to pursue a more exact realisation of the pure nature of sound to conjure up states of being, emotions and even geographical location.

Of his final electronic piece written in 1980 just before his retirement Lilburn said, "I think the last piece I did [Soundscape] really brought me full circle to what I'd been wanting to do all the time -- take the natural sound of the river and lake at Taupo and weave it into the texture of electronic sound and fuse them some way".

Electronic music is a broad church and includes everything from that theme to Dr Who and the disconcerting soundtrack to The Forbidden Planet by Louis and Bebe Barron to John Cage's experiments with cut-up tapes, those Switched on Bach albums by Walter (now Wendy) Carlos and complex symphonic pieces by Stockhausen which included processed voices and elelctro-chatter, bleeps and bops.

Electronic music is a broad church and includes everything from that theme to Dr Who and the disconcerting soundtrack to The Forbidden Planet by Louis and Bebe Barron to John Cage's experiments with cut-up tapes, those Switched on Bach albums by Walter (now Wendy) Carlos and complex symphonic pieces by Stockhausen which included processed voices and elelctro-chatter, bleeps and bops.

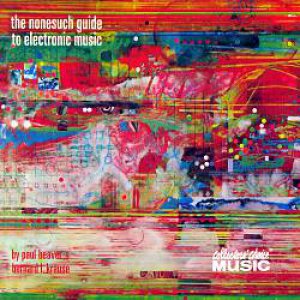

Many years ago Paul Beaver and Bernard Krause (themselves innovators in the field in the Sixties) produced the double vinyl The Nonesuch Guide to Electronic Music (the booklet looked like a maths textbook) which was a meticulously assembled collection of sounds with explanations as to how they were generated on the then-new Moog synthesiser. It was like an aural textbook.

I played it once right through . . . and put it on a shelf.

I played it once right through . . . and put it on a shelf.

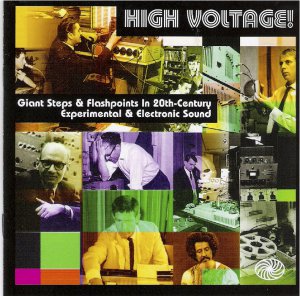

The recently released three CD set High Voltage -- compiled by Kris Needs who writes the informative liner essay -- is an easier place to start the learning curve (or fill some gaps in your electronic collection).

Needs juggles the material cleverly so after Pierre Henry's demanding 15 minute tone piece Le Viole d'Orphee (from 1953 which Needs descibes as "multi-layered devil's scrotum chorale-mangling") you get the melodic Feathered Serpent of the Aztecs by Les Baxter (1960, from the soundtrack to The Sacred Idol).

Across these discs you get the Big Names of electronic experimentation (Messiaen, Stockhausen, Varese, Xenakis, Cage) as well as the Tornados with the Joe Meek-written and produced Telstar, Sun Ra (as Sonny Blount) with Stuff Smith, that always eerie Forbidden Planet music and the Spotnicks from Sweden with their twangy instrumental The Rocket Man.

Yes, electronic music is a broad church and here Kris Needs is the inclusive bishop in residence.

* There is an excellent, informative and much recommended 3CD+DVD set of the complete electro-acoustic works of Douglas Lilburn available here.

* There is an excellent, informative and much recommended 3CD+DVD set of the complete electro-acoustic works of Douglas Lilburn available here.

You may also hear sound samples.

That is the site of SOUNZ, Centre for New Zealand Music and their homepage is here.

Like the sound of this? Then check out this.

post a comment