Graham Reid | | 32 min read

A strange journey begins with some good advice---the saint and storyteller---from Amalfi to ugly---the romance of Italy considered---a shocking discovery---the sad south---the idiot boy---the flying men of a faraway place---even more aerial saints---the hometown of the idiot boy---inflationary practices among the Catholics---once upon a time of miracles---the why and wherefore---a dark drive and a wisdom revealed.

Giuseppe's bird-nest eyebrows appear above the top of his newspaper. I have told him I am hiring a car and, nervously, am about to drive in Italy for the first time. He considers me in silence then patiently puts the paper down and offers some advice.

"Just ignore everyone else,'' he says with a laconic shrug of indifference and downturn of his mouth. "That is all. So, you just carry on and ignore everything that is all around you, and do it for yourself.''

He looks at me over his spectacles for a moment more then returns to his reading.

This is probably an excellent injunction, but here in Sorrento the streets can be impossibly narrow and wing mirrors invite collateral damage. Cars, motorcycles, trucks and vans argue for space with slow walking locals and the few inattentive tourists still drifting around at the end of the summer season.

And then there is the journey ahead: just the first few hours from here through Positano and down the Amalfi Coast are fraught with dangers. Two days previous I had taken a bus to picturesque Positano on a road where barely 50 metres is straight and the route hugs the cliff the whole way.

A moment's inattention and we would have been cast onto the rocks hundreds of metres below.

On the return trip I'd noticed the driver---who regularly sounded his horn on the hairpin bends---crossed himself a couple of times before particularly sharp, blind corners.

This was not encouraging.

At the hire car company the eye-catching, self-consciously aloof girl with heavy kohl eyeliner and immaculately manicured nails is equally indifferent to my qualms as she hands me the keys, documents and a map of the streets of Sorrento. Our trip will take in the Amalfi Coast and back roads through villages in the south, then motorways where cars pass at 200kph, and eventually up to the chaos that is Naples.

I take out every piece of insurance offered.

The only vehicle we can afford is a manual so I cautiously negotiate the way back to our hotel noting one advantage of a car is we don't have to deal with the gritty and gummy dog shit on these otherwise orderly and attractive tree-lined side streets.

My wife Megan and I pick up our bags, farewell a bemused Giuseppe, and I point the bonnet towards the narrow and easily-missed turnoff to Positano. I miss it easily and so circle back, trying to ignore everyone who is beeping or making gestures of frustration because I keep hitting the wipers instead of the indicator.

I make the loop to the turnoff and we are on our way, along the winding road across the high mountainous peninsula to where picturesque villages and towns seem to grow up the hillsides.

By chance we have started in the early afternoon when many people have shut up shop and got off the road, so there are fortunately few cars to ignore on this serpentine road. Laughably, every now and again, signs warn of sharp curves for the next few kilometres.

After a while I manage to enjoy the smell of orange groves, the whitewashed houses clinging to cliffs, the view of the shimmering, turquoise Mediterranean beneath us.

This may be a challenging drive along a narrow road, but it is also an appealing one---and the locals know it. We stop for fruit, cheeses and something to drink at a colourful barrow on a small lay-by above a sharp precipice. It is a blaze of fresh oranges, green beans and cucumbers, bright red peppers and yellow lemons. The sign says in English: ``Photo free with purchase''.

Before us are the white houses and hotels of Positano and the ceramic dome of the seaside church.

By Amalfi the driving has become effortless and I feel our journey to the town of Copertino in the southern region of Puglia has begun.

Copertino -- which makes it into few maps and is halfway down the heel of the boot---has an extraordinary claim to fame.

A little over 400 years ago Giuseppe Desa -- canonised in 1767 -- was born here.

And he flew.

***

The story of a flying saint came to me by chance. A week before going to Europe I was flicking the pages of Norman Douglas' 1915 travel book Old Calabria. Douglas had also chanced on the story of St Joseph, as he called him.

He tells of being in a bookshop in Naples and seeing an 18th century engraving in the front of a volume "which depicted a man raised above the ground without any visible means of support - flying, in short''.

Intrigued by this image and on being told it was Joseph of Copertino, Douglas bought that biography, and others, of this "seventeenth century pioneer of aviation''.

From his readings Douglas learned various stories of this saint, including that he would occasionally take passengers with him on spontaneous levitations.

The absurdity of these stories is amusing: there is one about Joseph tossing a sheep in the air, flying up to catch it then hovering at tree height for two hours; "his outdoor record'', quips Douglas.

But Douglas also appears to vouch for the veracity of some of these aerial adventures: Joseph was witnessed in flight by no less authority than Pope Urban VIII who proclaimed it a miracle. So unless you are calling the Pope a liar . . .

There were numerous airborne displays by Joseph -- indeed his frequent and unexpected levitations so irritated his fellow monks that the good and holy men were constantly shunting him off to some other monastery.

A usually reliable dictionary of saints offered further confirmation of Joseph's aerial antics: "These [levitations] are specially remarkable in Father Joseph's case,'' it said, "because the evidence adduced for some of the strangest of them is of considerable weight.''

And so, armed with curiosity, Douglas' book, and a willingness to drive on Italian roads starting with a spaghetti-like course down the Amalfi Coast, I resolved to go to lonely little Copertino to see the humble birthplace of St Joseph, the flying monk.

***

The Amalfi Coast wins effusive praise effortlessly: domino-like white houses and hotels stagger up sheer cliffs, small restaurants specialising in local seafood are commonplace, and the coastline is hard-edged in contrast with the smooth contours of the sea below. It is considered to be among the most spectacular drives in the world.

In towns like tiny Conca dei Marini, exotic and colourful Amalfi, and at Atrani the camera can work overtime, although it needs to be said there is already exactly the right number of garishly painted ceramic pots in the world being offered to tourists lacking taste and discernment.

We skip through unattractive Salerno and across country toward Potenza from where we will turn south east to the region of Puglia and down to the small town of Copertino.

The route takes us across the back of the Monti Picentini region and the car pulls hard against the steady incline.

We are in high farmland with few other vehicles to ignore, and even fewer small towns. It is a curious thing but the towns -- more correctly villages on mountain tops -- always appear larger in the distance.

The sheer-sided rocks on which they are built take on the appearance of houses. But when you get there, there is often no "there'' there.

We have left behind the region of Campania and are now in Basilicata, one of the least romantic parts of Italy. Some 25 years ago while studying Italian, I was introduced to the notion of the Mezzogiorno.

The conflated word translates literally to midday -- mezzo'' meaning middle and "giorno'', day -- and it is the time of heat and stupor. But when applied to the southern regions of Basilicata, Campagna, Puglia and Calabria it can be pejorative, the place of laziness.

We can feel the incessant energy of Naples and the calm beauties of Sorrento being shaved away with each passing town as we drive towards Potenza on empty back roads through impressive mountains. There's not that much to look forward to however.

"The best way to see Potenza is quickly and by night,'' says a guide book. "That way you'll avoid the sight of some of the most brutal housing blocks you are ever likely to see.''

It would be pleasing to report this is not only uncharitable but also unfair, however on arrival at this city we put away the camera for fear the lens might shatter. Potenza is a loop of motorway junctions in a valley with the town itself rising steeply up a sharp cliff. We drive to the top to find a hotel with a commanding view of hazy mountains, rooftops and the brutally ugly housing blocks.

That night, because there are no small trattoria within walking distance -- and everything is severely up-hill on the way back -- we go to the bar in the Grand Hotel Potenza before dinner. I have a glass of the excellent local red, Rio Nero, on the recommendation of the barman, but everything after that disappoints.

In the large and deserted dining room a couple of kids -- the chef's at a guess -- watch a typically loud and garishly lit television game show where the hostess looks like a transvestite wearing someone else's eyelashes.

The competing teams include an alarming number of bleached blond women with breast implants and sleazy-looking older -- if not elderly -- men.

One admirable feature of Italian television is it is not afraid to feature intelligent and articulate people talking direct to camera for long periods of time. On the other hand there are shows like this ridiculously protracted advertisement for silicon where no one has anything to say -- intelligent or otherwise -- for equally long periods of time.

I pick up the newspaper. There is, as always, some new Berlusconi scandal.

Dinner arrives and it is average at best.

Among the many myths about Italy -- and the most pre-eminent if you believe television celebrity chefs who tour this country with relentless and heavily sponsored enthusiasm -- is that the food is always excellent.

I too have had superb meals in towns, cities and people's homes. But as I poke listlessly at the tasteless veal before me I recall the lunch in Venice a week ago with my father-in-law.

We were at a small, family-run trattoria in the old Jewish ghetto area, some way from the tourist trail, and it wasn't high season. We wanted little more than a bottle of wine (which proved very good) and a plate of something to talk over. My spaghetti pescatora came with barely warmed chunks of surimi.

Italians can do lousy food as well as anyone.

Norman Douglas---considering the myths about Italy, especially a country which even today still has a baffling and protracted legal system wrote:

"How seriously we take this nation! Almost as seriously as we take ourselves. The reason is that most of us come to Italy too undiscerning, too reverent; in the pre-critical and pre-humorous stages. We arrive here stuffed with Renaissance ideals or classical lore, and view the present through coloured spectacles.''

***

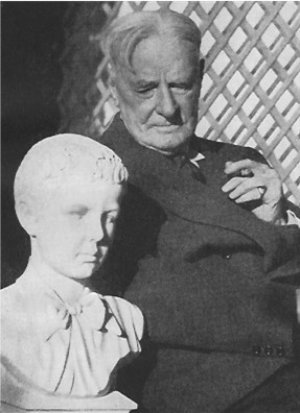

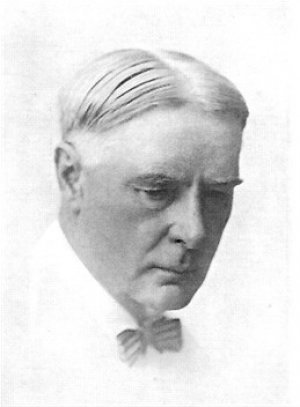

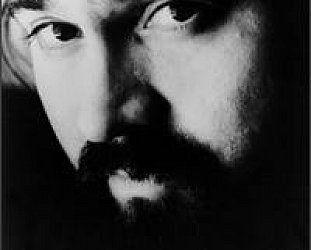

Douglas was a rare man: he possessed a sharp, insightful wit and keen critical faculties; spoke five languages and read both Latin and Greek; was adventurous, tough and resourceful; became renown as an unashamed hedonist; and played more than passable piano.

He also had a penchant for young boys.

Born in 1868 in Austria, Douglas -- whose family were Scottish -- spent much of his early life in various British and European schools (all of which he hated) and developed what he called a "healthy contempt for all education'', as the gifted often have the luxury of doing.

He loved natural history and at 20 visited Naples and Sorrento where he would spend much of his later life in a kind of elegant, self-indulgent exile.

He would celebrate the region as "Siren Land,'' a reference to the women in Greek myth who lured sailors to their deaths in this area.

He lived in London for much of his young manhood, initially writing on natural history, and then joined the diplomatic service. At 26 he was posted to St. Petersburg but two years later was obliged to leave the service quickly -- and the city of St Petersburg -- as the result of an indiscreet love affair with a woman whispered to have been a member of the Imperial family.

He settled in Naples where he bought and renovated a villa in the cool Posilippo area, and married his cousin Elizabeth FitzGibbon in 1898, with whom he had two sons.

Douglas wrote stories and pamphlets about the Isle of Capri where he moved after his divorce in 1904. In 1915 he published his most successful travel book, the freewheeling and surprisingly modern Old Calabria, the text I am travelling to Copertino with.

Yet there is more to Douglas than that of erudite travel writer, and author of the once very popular novel South Wind.

In 1916 he wrote London Games, a book about children's games based on close observation -- and, not so coincidentally, he was arrested for sexual misconduct with a young boy.

As Jonathan Keates observes in the introduction to the 1994 edition of Old Calabria, "after a crucial encounter in a Neapolitan street some years previously, Douglas had renounced heterosexuality for the kind of pederasty which transformed curly headed street urchins and unwashed ragamuffins on the beach into Hellenic ephebes [beautiful young men chosen for special instruction] and Ganymedes.''

Keates adds it doesn't take any great alertness to note the number of times in Old Calabria that Douglas engages young boys.

Not that he probably needed to. His companion -- never mentioned in the book -- was a 12-year old English boy called Eric Wolton whom he had picked up in London.

Eric, unfortunately, wrote no book of his “impressions”.

***

Less dramatically, I am travelling with Megan and she charts the course after unlovely Potenza down through Basilicata toward the coastal city of Taranto. The drive is relentlessly unappealing, and such small towns as I thought I might find to poke around in -- to drink cheap regional wine with locals and generally enjoy for their own sake -- are either non-existent or shabby and unwelcoming.

This adventure to Copertino was intended to take in quaint southern villages -- but it is increasingly apparent it isn't going to offer up much other than rock, scrappy land and amaro, the bitter liqueur which is the speciality of the region.

As Douglas observed, I have come here viewing the present through coloured spectacles.

How seriously we take this nation, how seriously we take ourselves.

We stop at some two-street, three-car village and in the bar at noon I greet the owner. He puts down our beers and turns away without a word. As do a number of others in the street where I amble hopefully, but briefly.

The local soccer team is getting off a swish bus. An away-game obviously. I ask, how did you do . . .

Nothing.

I go back inside. A group of old men is playing cards in the front room of the bar but there seems no point in interrupting them. One gets up and shuts the door on me when it looks like I might be walking towards them.

Fine. No one has to engage me let alone be interested in me.

We buy some amaro in a nearby shop and make our contribution to the local economy.

We move on slowly through the Mezzogiorno.

Many of the villages and towns we stop at -- hopefully looking for a conversation -- are punctuated by empty houses which confirm that a substantial percentage of this population has moved to the industrialised cities further south -- or north, or anywhere else -- in search of work.

This is born out when we reach the port city of Taranto, the single most frightful city I have ever seen. And I have been to brutally ugly Port Arthur in Texas, the oil town Janis Joplin left the moment she could.

We press on through the blank landscape which gives us time to consider the life of St Joseph who has drawn us into this unfortunate and inhospitable region.

***

The patron saint of pilots, air travellers and astronauts we know as St Joseph of Copertino was born Giuseppe Desa in 1603.

He was . . . let us say, a simple boy.

His playmates called him "bocca-aperta'' for his constantly agape mouth.

He was, to be blunt, dull-witted. One source refers to him as "The Dunce''.

References we might expect to be flattering say he was absent-minded, that a sudden noise would alarm him, he had no conversation, was underfed and sickly, caught every disease available, and was frequently slumped on death's doorstep.

Nobody, not even his long-suffering parents according to one account, much liked him.

It is reported by Norman Douglas that when the unfortunate Giuseppe was 17 he still couldn't distinguish brown bread from white. Around that time he saw a wandering friar begging and -- perhaps because he was unpopular, unwanted and incapable of holding down any other employment -- thought this might be something he could feasibly do.

Realistically, his options in smalltown Copertino were somewhat limited.

However because of his unappealing nature Giuseppe was refused admittance into various convents and, on the rare occasions he was accepted, the adolescent and awkward Giuseppe proved so intolerably clumsy that the monks who had engaged him to wash dishes and do sundry menial tasks would quickly dismiss him.

He was finally accepted as a servant at a Franciscan convent in Grottella near Copertino.

He may have been illiterate but he was faithful and dedicated, and seemed always to be happy, even though the monks made him sleep with the monastery mule. Giuseppe was a simple soul, and possibly a simpleton.

Yet he possessed something -- a child-like belief in the mercy of God perhaps? -- which attracted village folk to him.

Although incapable of study he was ordained by curious chance: with a group of candidates he was presented to the bishop for an oral examination on the Scriptures. However after hearing the first few candidates speak so persuasively, the bishop cut short the questioning and announced they would all be ordained.

Giuseppe did not have to endure a blind-test extrapolation on a given Biblical text, and was ordained at the age of 25 along with the other candidates.

Which explains why he is also the patron saint of test takers.

Giuseppe remained modest and knew his limitations. In a parallel with St Francis, in whose order he belonged, the man who slept with the mule now referred to himself as Brother Ass.

But then began a rare transformation.

Even as a boy Giuseppe had drifted into absent-minded dream states, but these now began to take the form of wonder-filled reveries and -- again, much like St Francis -- he began to experience God manifest in all things.

While in such states Giuseppe was impervious to pain: irritated fellow monks would poke him with pins and burning embers to try to rouse him. Over time the intensity of his reveries allowed him to depart from the constraints of this world and levitate.

It is said that in Copertino alone he flew more than 70 times.

When in his early 40s -- a good age during that period -- he was transferred to Assisi and in 1645 flew before the Spanish ambassador to the Pope, his wife, and a company of others. After that it seemed to be impossible to keep the idiot boy down.

It was said at the sight of a crucifix, an image of the Virgin or a holy relic he would fly in ecstasy.

His levitations were hailed as far away as France, Germany and Poland, and he counted among his admirers Catholic cardinals and European royalty, including the Duke of Brunswick who went to Assisi specifically to witness a flight . . . and converted from Lutheranism on witnessing Joseph sail across the room.

Giuseppe became so well-known that towards the end of his life -- during which he also drove out devils, healed the lame, caused the blind to see, and made wine and bread multiply -- his superiors confined him to a convent at Osimo.

There is a story about him preaching to sheep, much as St Francis delivered his Sermon To The Birds.

He died at Osimo at age 61. Or 60, depending on who you read.

Curiously Norman Douglas, who was so taken with the life of Joseph, didn't actually visit his birthplace of Copertino.

But I was going, and not just because of Douglas' account of an airborne individual.

Years ago I had been to another place where a whole race of men flew . . .

***

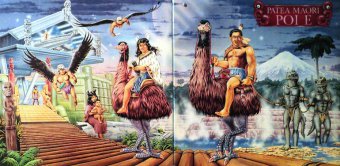

The afternoon was oppressively humid when Dalvanius Prime -- a huge man in a vivid pink and unflatteringly skin-hugging track suit -- drove me to the entrance of the Takirau Marae some 50 kilometres up the winding Waitotara River valley.

We were in New Zealand's Taranaki Province on the west coast of the North Island.

It was early 1988 and Dalvanius -- who died of cancer in late 2002 at age 54 -- was taking me to see the home of the kahui rere, the flying men.

Dalvanius -- or Dal, as he was known to most New Zealanders -- was one of the country's great musicians, a charismatic and good-humoured man, and in later life an inspirational cultural figure.

He had grown up playing music and singing on marae and in small halls, and in 1969 he formed the Fascinations with some family members. They won a talent quest and, encouraged, started touring Australasia. Dal proved himself remarkably gifted, and an intuitive singer, arranger and producer.

He was a big man with a huge heart, and appalling taste in clothes and interior design. The enormous gilt-framed image of the bust of Tutankhamun above his bed which he showed me proudly was actually a framed beach towel he'd bought at the British Museum gift shop.

On this afternoon, however, we were on a journey through his past to coincide with the release of an album by Patea Maori, the cultural group from the small and beleaguered nearby town of Patea.

The rural town had been in emotional and financial free-fall before Dal arrived to inspire local Maori.

The freezing works had closed and there was widespread unemployment.

The recession of the late 80s and early 90s hit Patea a decade before the rest of the country. Yet Dal saw the other side of the equation: Maori had been forced to rediscover their tikanga, their history and heritage, which included the distinctive local style of carving, and music.

Dal recorded the upbeat and catchy song Poi E with members of the local Maori Club, added the sound of miked-up poi to give it a percussive depth, and released it to the utter indifference of influential big city radio programmers who recoiled at a pop song sung in Maori.

It took 18 months for the song to climb the charts but in that time it became a national classic. Even now, decades later, it is hard to find someone who lived in New Zealand at that time -- no matter what age -- whose heart doesn't melt with sentimental affection on hearing it.

An album should have followed but it was delayed when Dal's mentor and musical partner Ngoi Pewhairangi -- who had written Poi E -- died when he and Patea Maori were touring in Europe on the back of their addictive hit.

They were fulfilling a promise he'd made her and the club members to take their music to the world. They'd even sung on the stage at the Apollo Theatre in New York which, for Dal -- a soul music lover whose record label Maui Music was to be the start of what he called "a Maori Motown'' -- must have been like arriving at the end of the rainbow.

The Poi E album eventually came out three years later -- it had been delayed further by the death in `86 of Dal's cousin Greg Carroll, road manager of U2 whom the band acknowledged in their song One Tree Hill.

When the album was released it went past most people. It didn't have another breakthrough song like Poi E but it was a minor masterpiece of production by Dal who worked on a thin budget.

"Everyone in the studio calls me Dalvanius De Mille,'' he laughed about his wide-screen sound. "My ultimate hero is Phil Spector who either made a classic or a real bomb.''

Dal had made both.

But on this afternoon in the valley he had something else on his mind. The fanciful cover for the Poi E album, illustrated by artist and film-maker Joe Wylie, was of figures from Maori mythology.

Half-men, half-tuatara characters emerge from the water and above them flying men circle in the air.

These flying men are the kahui rere and this river valley, the apex of the traditional boundary of the Ngaa Rauru people was where they lived.

The story -- Dal advised me not to say "the legend'' -- of the kahui rere, who originated at an island off the coast, is well documented. According to historian S. Percy Smith, writing in 1910, "a placenta was cast into the sea and in due course became a man whose name was Whanau-moana or Sea-born. He had wings, as had his descendants. At first none of these beings had stationary homes, but flew about from place to place, sometimes alighting on the tops of mountains.''

The last of these people were named Te Kahui Rere and settled in the low hills of the Waitotara River valley.

Dal points to the cliffs above the marae and indicates areas which are tapu because bones of kahui rere were found.

"The kahui rere were my ancestors and as a child of Ngaa Rauru, my tribal affiliation on my mother's side, the kahui rere were our tipuna, our ancestors, and are not just mythological.

"They are part of our living being.''

I look at the hills to which Dal is pointing.

Later I sit outside the hall of the marae while Dal is inside fiddling with a cheap tape recorder. The Maori here at Takirau marae, where he often came to relax away from the other world he lived in, had lost a cassette of some songs he had left for them to learn. He needs to re-record them.

A solitary fly buzzes in the thick air as his sweet voice lifts into the dense and unfamiliar humidity of the countryside around me.

The hills blaze a rich green and under a cloudless sky even my cynical city-born heart felt the timelessness and mysterious quality of this place.

In that magical moment -- and I tell Megan this as we drive through southern Italy to the birthplace of the idiot boy Giuseppe -- as I looked across the hilltops I truly believed that a long time ago maybe, just maybe, men could fly.

***

Giuseppe Desa was not the only aerial member of that extensive catalogue of misfits, the tragic and deluded, sometimes criminally suspect, and often inspirational figures known as Catholic saints.

Agnes of Montepulciano (1268--1327) was said to levitate while at prayer. She entered the monastery in Montepulciano at age nine, at 13 was charged by Pope Nicholas IV with establishing a monastery at Proceno, and became its prioress at 15.

This precocious over-achiever then went on an austerity binge: she slept on the ground with a stone for her pillow; lived on bread and water; but it is said flowers would bloom around her when she kneeled in prayer.

It was told at the moment of her death that all the babies in the region, no matter how young, began to speak of Agnes's piety and her passing.

Then there was also the levitating Catherine of Sienna (1347--1380) who at age 16 assigned herself to seclusion in her own home for three years, only leaving her room to go to Mass or Confession, lived on a spoonful of herbs a day and slept only a few hours.

She rejoined the world and gathered followers, experienced visions of Heaven and Hell, and was battered by the political vicissitudes of the church at this volatile period during which she advocated peace between the Papacy and various principalities. She wrote insightful books on the nature of Man and spirituality, and died aged 33.

Teresa of Avila (1515--1582) wrote in her autobiography of the divine ecstatic state during which the enraptured body is possessed by the spirit and is so intoxicated that the body will fly for a period of half an hour. She is said to have been uncomfortable while in this state and tried to prevent it happening.

"But little precautions are unavailing when Our Lord will have it otherwise''.

That Catholic-sounding quote comes from Paramhansa Yogananda's Autobiography of Yogi, published in 1950. The great mystic and teacher -- who introduced Hindu spirituality to the United States at the request of his guru Sri Yukteswar -- is recounting his experience of Bhaduri Mahasaya, a yogi who also, it is said, flew.

Of the habits of mystics and the divinely empowered Mahasaya told Yogananada: "Saints are not only rare but disconcerting. Even in scripture they are found embarrassing.''

Mahasaya might have been talking about St Joseph of Copertino and the trouble he gave his fellow monks when he would spontaneously levitate.

***

Human history is littered with myths about men and women who flew: Lilitu was a Sumerian flying demon who attacked men in their sleep; Icarus had help from wings his father Daedalus made; the Chinese emperor Shun was taught to fly by two women in his court; Perseus borrowed the winged shoes of Mercury; Hermes was the messenger of the Greek gods; Nike the daughter of Pallas and Styx whose image appears on Summer Olympics medals; Sally Field as The Flying Nun; Superman . . .

Flying men are found in folklore from Uganda -- the king Nakivingi using an invisible flying warrior Kibaga to hurl rocks down on his enemies -- and Egypt, to the aboriginal tribes of Australia, and the rich stories of Native Americans.

Black Elk had a vision of flying men when he was five, and Mojave tribes worshipped Mastamho, a warrior who transformed himself into an eagle.

The stories of Man entering a dream state and flying as a bird are legion.

And we wouldn't want to start counting the many ways in which Man flew: on winged horses, flying carpets; the Russian hag Baba Yaga who flew around in a mortar . . .

Flight has preoccupied Mankind since we first looked at birds and leaves blowing in the wind.

And Man has celebrated this in song: images of flight, soaring, wings and so forth litter popular and High Art songs through all cultures.

But if we suspend disbelief and surrender to the collective dream-memory of Man, why should a man not fly?

And if so, why not in the small town of Copertino?

***

The torpid town is dozing in the midmorning heat of a late summer day when we arrive. We circle the massive Castello Angioni and I park near a great arch topped by a statue of a beatific St Joseph, his outstretched arms reaching Heavenward.

Down a narrow lane opposite, between shuttered houses is the Santuario S Giuseppe da Copertino, the church built in his honour and on the site of his modest birthplace.

An old woman sees us coming, rude intruders, and scuttles back inside.

The whitewashed houses are silent, a dog trots in the narrow streets.

Giuseppe Desa, St Joseph, came from a family that was reasonably wealthy. His altruistic father, Felice Desa -- a carpenter it is said -- got into debt through signing promissory notes to help some friends. The friends disappeared and he had to answer for the debts. The authorities went looking for him and, to avoid jail, he hid in nearby scrub.

This seemingly pointless anecdote, probably apocryphal, sets the scene for what happened later.

When his wife, Francesca, was about to give birth to Giuseppe, the bailiffs arrived for her husband yet again and she sought refuge in the stable across the lane.

And so Giuseppe -- Saint Joseph -- was born in a stable.

Norman Douglas doubts this story and suggests it might have been a convenient, later fabrication since Giuseppe became a Franciscan and that is a branch of the Christian faith which embraces the humble.

The Franciscans were not above recreating their saints in imitation of Christ, St Francis himself -- despite coming from a well-to-do family -- just happened to be born in a stable as well, La Stalletta near the main piazza in Assisi.

The chapel on the site has become a place where locals pray for the needs of their children, and where expectant mothers go to pray for a healthy pregnancy.

In his book In the Footsteps of Francis and Clare, the writer Roch Niemer who takes tour groups around Franciscan holy sites -- acknowledges this story of St Francis is known only through legend, no documents exist to prove it.

He cites an old translation which says, " . . . a stranger came to the threshold of the blessed house [of Francis's mother Pica who was having trouble giving birth] and gave the young wife the mysterious message that she would not be able to give birth to her baby except in a stable, in the same way that Mary bore Jesus. So Pica was taken to the stable next to the family house. There, on the straw, the baby who would become St Francis first saw the light of day.''

This legend, says Niemer, is "the gentle starting point'' for Francis's conformity to Christ.

So too, the legend that Giuseppe was born in similar Christ-like circumstances -- and that both had fathers who were carpenters simply added to Giuseppe's cachet.

Whatever the truth, a church was built to enclose the stable in Copertino which now contains the relic of Giuseppe's heart.

It is a moving, ill-lit shrine with that relic on one wall and the suggestions of stable door scattered around. Sort of a Disneyworld verisimilitude of a stable.

But on the walls of the church are two paintings, one on each side of the bright altar, both depicting St Joseph in flight.

Inside this empty church, despite the soaring height and the gleaming altar, it feels gloomy and\ldots

I squint into the paintings and the altarpiece, searching for meaning.

Later in the afternoon a few old men and a middle-aged woman come in to offer prayers and the priest holds confession.

There is a sense of the little-changing ages here.

The old people stare briefly, but with unnerving intensity, then shuffle off. Even though I am sitting in respectful silence I am made to feel like the rude intruder that undoubtedly I am.

It is humid and a solitary fly buzzes noisily in the thick air.

Outside I walk towards the middle-aged priest in black robes who pointedly turns away, then disappears through a small wooden door beside the chapel.

I stand outside the church and birthplace of Saint Joseph and try to conjure up what this place must have looked like all those centuries ago: the stable; the idiot boy playing in the dirty streets being ignored by the other children of the village; his long-suffering parents making a bolt for it when they saw him coming towards them . . .

It has been a long journey and an even more strange pilgrimage for me, not even a lapsed Catholic, to have made. I stand here at the birthplace of this flying saint and feel . . . Well, not a lot actually.

Rain spits down and Megan steps in some gritty and gummy dogshit outside the saint's house.

Oh, fuckit. Saints? Who needs `em?

***

Most people -- especially those not of a faith which believes in them -- have become immune to the existence of saints. We have heard about so damn many of them. Especially in the last quarter of the 20th century when saints were arriving faster than boy bands and controversial Madonna videos.

The late Pope John Paul II, history's most frequent-flyer pope, rarely kissed the tarmac of a new country without first beatifying or canonising some local contenders for sainthood.

The man was profligate when it came to opening the Gates of Heaven to the most hallowed.

As a Vatican source once observed on the induction of a new batch of these holies-in-a-hurry: "From Papua New Guinea to Paraguay, Australia to Africa, he wants to give every colour, every country, every culture a saint to believe in.''

John Paul II was referred to as "the saint-maker'' because of his propensity to create saints, and more than just occasionally he was elevating some into the white-robed pantheon whose history was unknown or faith suspect.

John Paul II created more new saints than all popes in the previous four centuries combined. And you can add to that more than 1300 in the transit lounge awaiting sainthood through beatification.

Sainthood became a growth industry under his papacy and, as in the case of the Martyrs of Vietnam -- 100 declared saints in 1998 -- he was sometimes a volume dealer.

Four years earlier he'd made saints of 103 priests, missionaries and lay people who died in the early days of the Church in Korea. In late 2000 he canonised another 120 martyrs in China, many of them murdered in the Boxer Rebellion or under the Communist regime. Saints made to order.

Around half of all new saints under John Paul II came from Asia and were either local converts or missionaries. However given the paucity of information about many, questions have been raised about just how "holy'' some of these people were.

Not much is known about the short life of the Vietnamese man now named John Dat, for example.

He was born in West Tonkin in 1764, ordained as a Catholic priest in 1798 then immediately arrested in one of the periodic anti-Catholic purges which punctuate Vietnam's recent history. After three months imprisonment he was beheaded for refusing to deny his faith.

Johnny, we hardly knew you . . .

In 1900 he was beatified by Pope Leo XIII, then in 1988 was canonised by Pope John Paul II, joining that hit list of the 100 Martyrs of Vietnam.

What is of interest to those outside the Catholic Church---a question which seems not to trouble the faithful -- is why John Paul II embarked on what John Allen, columnist for the National Catholic Reporter called "halo inflation''.

"His zeal for saint-making,'' said Vatican specialist Orazio La Rocca, a role not dissimilar to a "Royal watcher'' in Britain, "ultimately conveys a simple message to the faithful: Anyone can aspire to holiness, from the simplest priest who prays daily, to the mother who dies because she refuses an abortion, along with this century's many martyrs.''

In short, he was responding to the needs of his broad constituency by allowing for local models of holiness in an increasingly secular world.

Secular writers have condescendingly referred to El Pele -- Cerefino Jiminez Malla, shot by firing squad in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War for publicly defending a priest, and beatified in 1997 -- as "an illiterate horse trader''.

But that doesn't trouble the similarly illiterate faithful who identify with his deeds and faith.

This need is also evident among more sophisticated peoples. As Franco Ferrerotta, a sociologist at Rome University observed, "In an increasingly consumer-influenced society there is a need for a role model, some sign of where to go. People have always thought things could only get better in an ever-richer society. But now most people are well off, they notice the same problems still exist. It has created a deep-rooted sense of ill-being.''

So what is true is, despite secular cynicism, many people still feel the need to have heroic models, whether they be Diana Princess of Wales or football-flicker David Beckham.

Such people embody attributes many aspire to. So it is with saints.

In that light Giuseppe Desa, a simpleton from a small town in impoverished 17th century Italy, had all the makings of an inspirational figure for the faithful, peasant constituency.

A century ago Norman Douglas identified this need for saints and the Church's local agents had a willingness to supply them. Less a cynic than an observer, he noted in Old Calabria, "From this rank soil there sprang up an exotic efflorescence of holiness. If south Italy swarmed with sinners . . . it also swarmed with saints.''

He then considers the nature of the many saints in the south and says one cannot help but note the great uniformity of their lives, "a kind of family resemblance''.

"These saints are alike -- monotonously alike if you care to say so -- in their chastity and other official virtues . . . Nearly all of them could fly, more or less; nearly all of them could cure diseases and cause the clouds to rain; nearly all were illiterate; and every one of them died in the odour of sanctity -- with roseate complexion, sweet smelling corpse and flexible limbs.

"Yet each one has his particular gifts, his strong point. Joseph of Copertino specialised in flying; others were conspicuous for their heroism in sitting in hot baths, devouring ordure, tormenting themselves with pins, and so forth.''

Douglas argues this diversity of gifts is because of the furious competition between the various monastic orders of the time which led to never-ending litigation and complaints to headquarters in Rome.

"Every one of these saints, from the first drawing of his divine talents, was surrounded by an atmosphere of jealous hatred on the part of his co-religionists. If one order came out with a flying wonder, another, in frantic emulation, would introduce some new speciality to eclipse his fame---something in the fasting line, it may be; or a female mystic whose palpitating letters to Jesus Christ would melt all readers to pity.''

So Giuseppe Desa -- "bocca aperta'' -- and soon to become St Joseph of Copertino?

He served a political purpose for his order and was someone from the ranks of the great illiterate in the villages and remote hillside towns of the peninsula's impoverished Mezzogiorno. His miraculous life gave hope to those who believed a benign God could intervene in their lives and protect them.

St Joseph's elevation illustrated that all Mankind -- however simple, open-mouthed and unpopular -- possessed the potential for holiness.

The reports of his levitations may have been driven by the powerful symbolism inherent in the act -- ascending heavenward -- and encouraged by those in whose best political interest it was to have an idiot boy a saint.

That would explain his elevation into the realms of the most holy.

He may, of course, also have flown.

***

We live in a world lacking of wonder, where ecstasy is to be mistrusted and the faith of simple souls invites derision. In the 16th century the adjective "naive'' meant original and natural, by extension an endearing simplicity.

And today?

A once healthy scepticism has hardened into an effortless and often reflexive cynicism which allows us to refute without question the possibility of divine ecstasy.

Much of this has been brought on by those who advocate the supremacy of reason.

The writer Felipe Fernandez-Armesto in his book Truth discusses reason in a chapter which opens with a quotation by G. K. Chesterton: "Reason itself is a matter of faith. It is an act of faith to assert that our thoughts have any relation to reality''.

This is a time bereft of miracles, but it might be pleasant occasionally to be open once more to the impossibility of them.

The American essayist and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson said, "If we meet no gods it is because we harbour none''.

However he also said, "I hate quotations. Tell me what you know.''

So . . .

***

We leave suspicious little Copertino and drive to Lecce.

It is the home of alarmingly over-powering baroque architecture and, as it transpires, a hideously green motel room with an unimpeded view of a parking lot for longhaul trucks.

On the way through the city, however, we get caught in a downpour at dusk, and a Saturday night traffic jam.

For an hour we drive around lost and confused, me increasingly angry with dead-end streets, roadworks around the chiesa, and the sullen southern people who refuse to understand my attempts at whatever Italian I can muster when I ask for directions.

As we drive down a long piece of poorly illuminated and rain-wracked road we have seen twice previously I am cursing myself: what had seemed a promising trip in search of a saint -- and maybe some kind of insight into something unspecified and nameless -- has actually been an utter waste of time.

There was no great epiphany, in all likelihood there was never going to be.

But maybe this journey through the beautiful then bloody awful barren landscapes, engaging with the unusual and disparate lives of Norman Douglas and the idiot boy who flew, and the memory of that rare time with Dalvanius and the spirit of the kahui rere, have been their own rewards?

As insipid green light from streetlamps sparkles on the windscreen, I try again to understand the world of Giuseppe Desa the flying saint, and of popes and miracles.

I wait for a sudden, deserved, insight in the night -- but nothing comes. That world of faith and flying men seems so very far away.

As we are halted by carabinieri who step out of the blackness I am thinking, a flying man?

Jesusgod, I wish.

White gloves in the night wave us on into more crosstown traffic and I concentrate on the rain-lashed road ahead.

And where is St Joseph of Copertino, the idiot boy born Giuseppe Desa, in all this?

Nowhere.

I find instead I am thinking of the other Giuseppe, the bushy-browed one back in Sorrento. The one who was as indifferent as this rain and the people we have encountered on this seemingly annoying and pointless -- but odd, and in some ways, curiously-rewarding -- journey.

Maybe all along it was that Guiseppe who offered the lesson I have been looking for as I have travelled.

So I will just carry on and ignore everything that is all around me.

And do it for myself.

DEDICATION

As always to my sons Julian, Ab and Cymon Reid who are out there in the world on their own journeys. Travel safe and long my darlings. As musicians you are doing God's work in this world.

To my wife Megan Stunzner whose love and support and companionship -- at home and abroad -- has enriched my life immeasurably and sustains me.

And to my parents, Graham Paterson Reid (1913-1986) and Margaret Noble Lamb Reid, nee Stevens (1922-2004). Thank you in your sad absence: you made travel seem part of the contract of living. I miss you more with each whispering day.

Harold Ellison - Jan 14, 2014

You don't receive enough recognition for your talents. GRAHAM REPLIES: That is very generous . . . and I am not so humble as to disagree with you! Ho ho ho.

SaveAlistair M - Jan 14, 2014

A really interesting, well written and insightful read.

SaveLisa - May 11, 2016

Thanks Mr. Reid... I loved this tale; it brought back some distant travel memories and reminded me again why it's best to catch a train from Salerno to Palermo and not womble about too much on the way :)

Savepost a comment