Graham Reid | | 11 min read

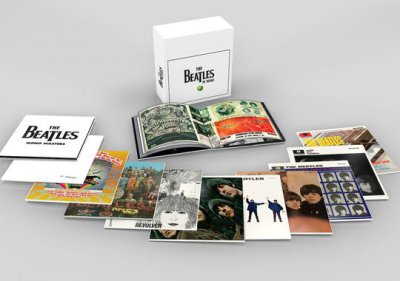

The Beatles: Only a Northern Song (mono)

At last!

Although seriously serious old Beatles' fans didn't have long to wait.

Just fortysomething years after the band broke up . . . but a mere five years since their albums and singles were given long overdue remastered reissue, here it is.

Mono Beatles at last on vinyl record again . . . a real back to the . . .

Well, in truth, not "back to the future" of cliche but back to the past which is where the Beatles' music was actually created.

Those earlier Beatles remasters came in mono and vinyl mixes in CD box sets (purists rightly prefer the mono versions right up to and – oddly enough – including Sgt Peppers), but hardcore fans and audiophile obsessives were waiting for the remastered albums on vinyl. In mono.

The stereo set arrived two years ago (on 180gm vinyl in a box with an excellent album-sized hardback book), but only now are the hardcore folk getting what they want: the Beatles on record in mono.

Again they come in a box (but with a new and different hardback book) and the vinyl albums can be purchased individually.

Good.

Some might say you are better off without Beatles for Sale and Let It Be, two of the least consistent and interesting albums in their output.

The debate about sound quality – the

old “vinyl, CD or download?” question – will never be resolved,

largely because unless you apply sonic mathematics to it, the sound quality

is in the ear of the be-hearer.

The debate about sound quality – the

old “vinyl, CD or download?” question – will never be resolved,

largely because unless you apply sonic mathematics to it, the sound quality

is in the ear of the be-hearer.

And as aside from the condition of your ears -- you can perhaps imagine the damage to mine -- it all depends on what kind of equipment you have.

I'm far from an audiophile (as Elsewhere readers know, a $4 scratched album with two good songs is actually my kind of thing) but even on my old Technics system a vinyl record does sound wider and deeper than a CD played through the same system.

And I won't even mention what CDs sound like through a computer as opposed to vinyl.

But that's just me, my ears, my systems and my records.

So let's not go into that discussion about “quality of sound” but advance other more obvious reasons why vinyl records are superior: they look better, have a degree of permanence that a download doesn't, and album covers could often be artistic (and yes, sometimes even really bad kitschy art). You don't see CD covers framed, do you?

An album cover can set off a swag of emotional resonances – think Dark Side of the Moon, Nevermind, With the Beatles, the Ramones first album and anything by Cher -- by way of obvious example

And you can't see album covers from the Eighties on a download. Think of all that big hair you are missing if you can't see a Thompson Twins or Stray Cats cover.

So now that JB HiFi are putting the

old-fashioned new-fangled vinyl (quality re-pressings) into their

stores -- the Beatles in Mono box a tidy $500 post-free within New Zealand (see here) --let's consider some piece of large plastic (some in framable

covers, so you can enjoy them even before you get a turntable) that

you should have . . . and follow those intralink for even greater considerations of the music.

So now that JB HiFi are putting the

old-fashioned new-fangled vinyl (quality re-pressings) into their

stores -- the Beatles in Mono box a tidy $500 post-free within New Zealand (see here) --let's consider some piece of large plastic (some in framable

covers, so you can enjoy them even before you get a turntable) that

you should have . . . and follow those intralink for even greater considerations of the music.

And we offer some suggestion of where to go after you've digested and enjoyed this one.

Here we go with . . .

TWELVE TERRIFIC TWELVE INCHES

a beginners guide to collecting

vinyl .............

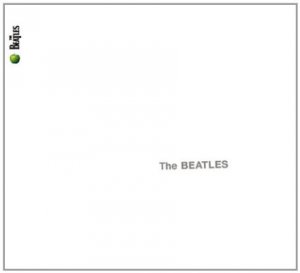

The Beatles: The Beatles (1968). And how appropriate to start a conversation about great album cover art with this one, aka “The White Album” named for it's plain, gatefold cover.

The Beatles: The Beatles (1968). And how appropriate to start a conversation about great album cover art with this one, aka “The White Album” named for it's plain, gatefold cover.

This double album has grown in stature over the decades because the volume of diverse, fascinating musical information it contains. It's all here from classic rock'n'roll with a twist (Back in the USSR refers to Chuck Berry and the Beach Boys), raw-throated rock (Everybody's Got Something to Hide, Why Don't We Do It n the Road?), humour (Bungalow Bill, Harrison's snarky Piggies), folk (Lennon's Mother Nature's Son, McCartney's Blackbird), faux-blues (Lennon's Yer Blues), country (Rocky Raccoon) and of course Lennon's surrealism (Happiness is a Warm Gun, the referential Glass Onion).

Harrison got away his classic While My Guitar Gently Weeps (with uncredited Eric Clapton doing the guitar solo) and the ethereal Long, Long, Long. And Ringo at last got to record his Don't Pass Me By which he'd first played to them back in '62 when he joined the band.

Ironically the original title suggests a band, but by this time there were three totally distinct songwriters at work and never sounded less like a group.

Throw in the eight and half minute sonic tapestry of Revolution 9 and close with Lennon's heavily orchestrated lullaby Good Night sung by Ringo and you have plenty to decode.

It also gave the lie to Lennon writing the rockers and McCartney being the balladeer: among the standouts are Lennon's delicate Julia to his late mother and McCartney's searing proto-meta of Helter Skelter.

The Rosetta Stone of Beatle music.

Next: The Beatles, Revolver

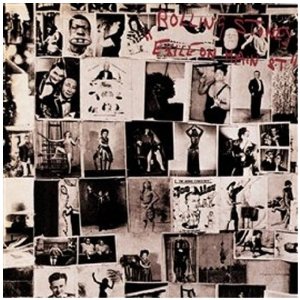

The Rolling Stones: Exile on Main St

(1972). On the face of it, a sprawling and seemingly shapeless

double album, much of it recorded during endless and often addled

sessions at Keith Richard's rented mansion in the south of France.

The Rolling Stones: Exile on Main St

(1972). On the face of it, a sprawling and seemingly shapeless

double album, much of it recorded during endless and often addled

sessions at Keith Richard's rented mansion in the south of France.

Weary of their legal battles, touring and maybe even cranking out chart-topping albums they reverted to the sounds which inspired them (dark and rude blues, raw rock'n'roll) but also indulged in Keith Richards' discovery of country music through his friendship with Gram Parsons who was hanging around the house.

This collection – roughly recorded in many places which adds an extra allure – is very much Keith's album and even today Mick Jagger says it is far from his favourite. Richards' would never have quite this much control over an album or the band again, and it wasn't too well received at the time.

But very quickly people came to realise here was the essence of the Stones, and it is that lack of concern for flicking out obvious singles (although Happy and Tumbling Dice became mainstays of their live shows) which means this rises above its era and has a longevity many of their albums don't.

The Rolling Stones in a rare moment when Mick isn't centre-frame.

Next: The Rolling Stones, Beggar's Banquet; The Black Crowes, Before the Frost . . . Until the Freeze

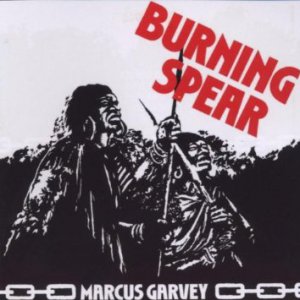

Burning Spear: Marcus Garvey (1975).

Along with the great Bunny Wailer, Winston Rodney – aka Burning

Spear – kept the core values of mystical Rastafarianism and

political Garveyite beliefs close to his heart.

Burning Spear: Marcus Garvey (1975).

Along with the great Bunny Wailer, Winston Rodney – aka Burning

Spear – kept the core values of mystical Rastafarianism and

political Garveyite beliefs close to his heart.

With the cream of Jamaican studio players, the mighty Spear was uncompromising in his beliefs (Marcus Garvey, Old Marcus Garvey) and his sense of Jamaican culture (Slavery Days) so the listener is dropped deep into the Afro-centric world of Jamaican reggae.

At times sounding like an Old Testament prophet, Spear delivers these sermons, thoughts and stories with such weight that you know you are in the presence of genius. A few months later the dub version of this was released as Garvey's Ghost and it is an essential companion volume.

This is deep immersion into JA culture and not for the faint-hearted who have Bob Marley's Legend album on repeat-play at summer barbecues.

Next: Bunny Wailer, Blackheart Man; Burning Spear, Social Living/Living Dub

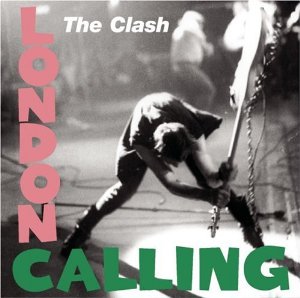

The Clash: London Calling (1979).

The point when punk fury was codified into coherence and where,

across two records, the Clash expanded their reach back into classic

Fifties rock'n'roll (Brand New Cadillac), across to contemporary ska

and reggae (Rudie Can't Fail, Revolution Rock) nodding towards

pop-blues (Wrong 'Em Boyo) and even accepting enjoyable pop (Hateful,

Death or Glory) alongside politicised power pop (Spanish Bombs).

The Clash: London Calling (1979).

The point when punk fury was codified into coherence and where,

across two records, the Clash expanded their reach back into classic

Fifties rock'n'roll (Brand New Cadillac), across to contemporary ska

and reggae (Rudie Can't Fail, Revolution Rock) nodding towards

pop-blues (Wrong 'Em Boyo) and even accepting enjoyable pop (Hateful,

Death or Glory) alongside politicised power pop (Spanish Bombs).

There's plenty of self-mythologising going on (the killer title track, Guns of Brixton) and of course as with all double albums there are a couple of flat spots across the 19 songs, and sometimes the stabs at politics and consumerism are weighed down by worthiness.

But this was courageous, ambitious and set a new benchmark for post-punk rock'n'roll bands. Some critics said this was the time when the Clash became the Rolling Stones, but you couldn't deny their seriousness and commitment.

And songs like London Calling, Train in Vain, the New Wave-influenced Lost in the Supermarket and others have stood the test of time.

Next: The Jam, Setting Sons; Neil Young, Live Rust

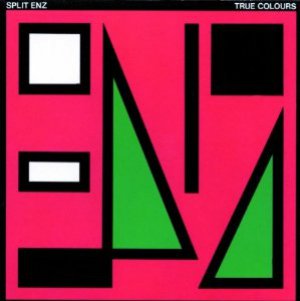

Split Enz, True Colours (1980).

At the time released on Tim Finn's 28th birthday and

coming in different colour combinations on the cover (so take your

time when choosing which you want to live with), this was the Enz's

most commercially successful album but also found Tim at the top of

his songwriting.

Split Enz, True Colours (1980).

At the time released on Tim Finn's 28th birthday and

coming in different colour combinations on the cover (so take your

time when choosing which you want to live with), this was the Enz's

most commercially successful album but also found Tim at the top of

his songwriting.

I Hope I Never and Poor Boy are classics in their catalogue and the former is one of Tim's most affecting and enduring performances, the latter a beautifully arranged piece of emotionally engaging dark pop.

There is Tim-intensity here too (Shark Attack, Nobody Takes Me Seriously). Eddie Rayner's extraordinary keyboard work (everywhere) and of course the new player in the game, Neil Finn, whose I Got You was classy slice of New Wave-influenced pop and a sign of things to come.

Neil also contributed the memorable What's the Matter With You and Missing Person.

And lest anyone think this is locked in its period, the closing instrumental The Choral Sea sounds like it could slip into a DJ set in dancefloor clubland (and perhaps cries out for a remix).

Next: Split Enz, Waiata; Crowded House, Temple of the Low Men

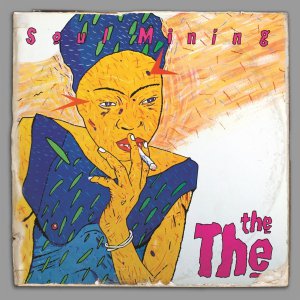

The The, Soul Mining (1983).

Just reissued on vinyl as a two-record set (the second album includes

12” versions and American mixes), this remarkable album by Matt

Johnson – aka The The -- was a bridge between pure pop, New Wave,

synth pop, post-punk, power pop and – when pianist Jools Holland

entered on the glorious seven minutes of Uncertain Smile – even

jazz.

The The, Soul Mining (1983).

Just reissued on vinyl as a two-record set (the second album includes

12” versions and American mixes), this remarkable album by Matt

Johnson – aka The The -- was a bridge between pure pop, New Wave,

synth pop, post-punk, power pop and – when pianist Jools Holland

entered on the glorious seven minutes of Uncertain Smile – even

jazz.

Oddly enough Johnson says his influences were the taut minimalism of Wire and the odd anti-pop of This Heat . . . and although you can hear some of that in these seven tightly-wound and often disillusioned lyrics, the man was also a child of John Lennon and the boundary-ignoring Tim Buckley.

So radio-smarts, an exploratory and inquisitive nature, the angst of the times and a pop sensibility all came together on an album – in striking cover art by Johnson's uncredited brother Andy – which still sounds fresh and engrossing some three decades on.

Next: Talk Talk, Spirit of Eden; The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Time Out; Heaven 17, Penthouse and Pavement

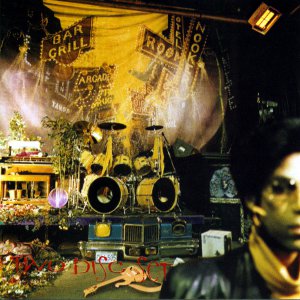

Prince, Sign o' the Times (1987).

The jury will always be out on what the best Prince album is –

there's a good case for 85's Around the World in a Day if you read it

as his Sgt Peppers – but this double vinyl was the result on an

enormously prolific period when he was bouncing between funk

minimalism (the classic title track), soul balladry, psych-rock with

a black spin, r'n'b, pop and whatever else he could pull out of his

man-bag.

Prince, Sign o' the Times (1987).

The jury will always be out on what the best Prince album is –

there's a good case for 85's Around the World in a Day if you read it

as his Sgt Peppers – but this double vinyl was the result on an

enormously prolific period when he was bouncing between funk

minimalism (the classic title track), soul balladry, psych-rock with

a black spin, r'n'b, pop and whatever else he could pull out of his

man-bag.

The exceptional title track nailed the era (Aids, crack, heroin, bad news on the news) with world weariness and hurt. But elsewhere he partied, bent the gender divide, squealed like Michael Jackson, channeled Hendrix and Motown and P-funk, used the studio like an instrument and never sounded so in command of his art. Even now this repeat-play four sides of vinyl.

Next: Prince, Purple Rain; Funkadelic, Maggot Brain; Th Jimi Hendrix Experience, Are You Experienced; Sly and the Family Stone, Stand

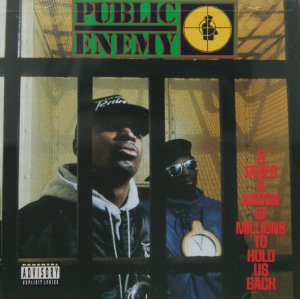

Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of

Millions to Hold Us Back (1988). Hip-hop has never sounded so

ferocious, essential, globally connected and as alive as on this

album which, within seconds, sounded a warning siren, came on like a

live album and referred to history (Gil Scott Heron) before dropping

you right into the black'n'angry present tense by namechecking Rev

Louis Farrakhan over desperate scratching.

Public Enemy: It Takes a Nation of

Millions to Hold Us Back (1988). Hip-hop has never sounded so

ferocious, essential, globally connected and as alive as on this

album which, within seconds, sounded a warning siren, came on like a

live album and referred to history (Gil Scott Heron) before dropping

you right into the black'n'angry present tense by namechecking Rev

Louis Farrakhan over desperate scratching.

If for some reason hip-hop was off your radar this is where you start: it was and is more rock'n'roll than anything at the time, and even now.

Memorable samples and mad scratching by Terminator X, clear politicised poetry and rage from Chuck D, crazy Flavor Flav . . .

Believe the hype in this case, “Yee-ah bwoy”.

Next: Public Enemy, Fear of a Black Planet

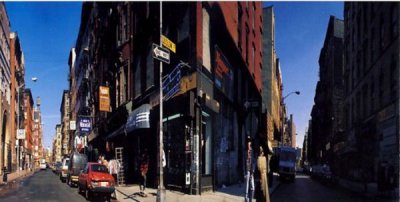

Beastie Boys: Paul's Boutique

(1989). If you want to be shallow, here's where vinyl gatefold

covers come into their own. This is a fold-out art statement –

which makes no sense on small scale CD – and is iconic in the

hip-hop world and beyond.

Beastie Boys: Paul's Boutique

(1989). If you want to be shallow, here's where vinyl gatefold

covers come into their own. This is a fold-out art statement –

which makes no sense on small scale CD – and is iconic in the

hip-hop world and beyond.

For decades people have lined up on New York's Rivington St in downtown – just as people of another generation do at the Abbey Road crossing – to get a similar photo.

More seriously, here the Beasties proved they were more than a pan-flash after Licensed to Ill (“you got to fight for your right to party”/No Sleep till Brooklyn etc) and threw in a whole album's worth of samples (other than their vocals) which stands a landmark.

It's snotty, whiny, white-boy hip-hop but so clever their left-field genius was undeniable. And sometimes – that rarest of commodities in hip-hop and rock – just very funny.

“Hey ladeeez”

Next: The Beastie Boys, Licensed to Ill; The Streets, A Grand Don't Come For Free

White Stripes: Elephant (2003). There's rarely been an opening track

with quite the visceral but understated and minimalist pop-power as

Seven Nation Army here. It channels equally Sixties garageband rock,

Led Zeppelin and some white-boy idea of inner-city black blues.

White Stripes: Elephant (2003). There's rarely been an opening track

with quite the visceral but understated and minimalist pop-power as

Seven Nation Army here. It channels equally Sixties garageband rock,

Led Zeppelin and some white-boy idea of inner-city black blues.

Any opening song which has that bass-line, namechecks the Queen of England, the hounds of hell and Wichita is probably setting you up for bent genius, and Jack White delivered across a Beatles-length album (14 songs) which came in a great – and yes, framable – cover.

This was an “album” of the old style: short and sharp songs, not ashamed to include covers, notably Bacharach-David's I Just Don't Know What To Do With Myself after the pedal-to-metal Black Math and bent guitar-rock-cum-wordy folk of There's No Home.

And it referenced itself in the past with Ball and Biscuit which out Led's Zeppelin. Jack and Meg White with Holly Golightly also offered the bedroom country-folk silliness of Well, It's True . . . which was sort of their Her Majesty's a Pretty Nice Girl,.

The White Stripes made many very, very good albums . . . but they nailed it on this one.

Next: Dead Moon, Unknown Passage; Led Zeppelin, Led Zeppelin

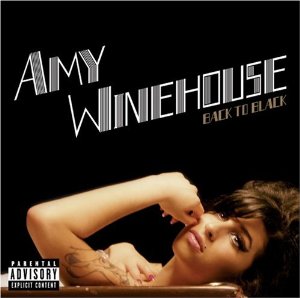

Amy Winehouse: Back to Black (2006).

Stupid girl who was so full of promise.

Amy Winehouse: Back to Black (2006).

Stupid girl who was so full of promise.

If her debut Frank announced her, this astonishing soul-cum-funk album full of blues and pain proved she had mastered Motown, that most difficult art of autobiographical writing, and could flip the switch to inhabit the world of hurt Billie Holiday, celebratory Dinah Ross, the insightful world of Hal David's insightful lyrics, a Rasta sista, Bond theme songs . . .

Every time you hear this album you'll be utterly seduced by it, and just angry at that stupid, damaged girl who was not just a rare interpretive singer but a soul-baring poet gone far too soon.

Next: Aretha Franklin, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You; Nina Simone, Little Girl Blue

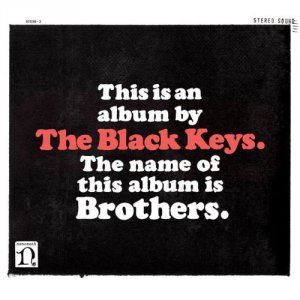

The Black Keys: Brothers (2010).

Their follow-up El Camino is

more popular but this one – which started life in the rundown

Muscle Shoals Recording Studio in Alabama – captures them moving

on.

The Black Keys: Brothers (2010).

Their follow-up El Camino is

more popular but this one – which started life in the rundown

Muscle Shoals Recording Studio in Alabama – captures them moving

on.

Here they went from raw blues into funky rock, edgy and bitter pop, Stax soul, a smidgen of rockabilly blues mixed with T. Rex (Howling for You), Etta James-styled midnight blue hurt (The Go Getter) and a courageous but successful version of Jerry Butler's heart-aching Never Gonna Give You Up before their own equally soulful These Days.

A breakthrough album for them (and their audience) and the start of a long love affair if you were a bit indifferent about their earlier albums.

Cool non-cover cover also, to end a column which advanced the case for vinyl because of the cover art and started with a plain white sleeve.

Ironies abound.

Next: Clarence Carter; The Dynamic Clarence Carter; Otis Redding, Otis Blue

Serious about sound? Then check this out.

Dave - Sep 2, 2014

Portishead - Dummy.

SaveSlint - Spiderland.

post a comment