Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Exploration was different in the old days. Consider the case of the Arctic adventurer Sir John Franklin who lead an 1845 expedition of 129 men.

When they set off 59-year old Franklin – who weighed 15 stone and was just 5ft 6in – took with him 1700 books, a hand organ, fine china and expensive cutlery . . . and his pet monkey.

They were never heard of again.

It seems from Inuit accounts that a few involved in Franklin's folly took to cannibalism in their final days.

There is a fine line –

actually no there isn't, there's a great chasm – between

foolhardiness and heroism. And Franklin (who had lead two previous

expeditions into the ice but apparently complained of the cold in

London) was firmly in the camp of the bloody idiots.

There is a fine line –

actually no there isn't, there's a great chasm – between

foolhardiness and heroism. And Franklin (who had lead two previous

expeditions into the ice but apparently complained of the cold in

London) was firmly in the camp of the bloody idiots.

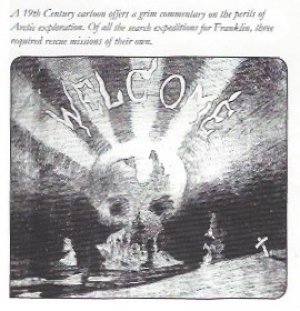

Ironically there were more than a dozen government and privately-funded search parties sent out to find Franklin and his companions – three of which had to be rescued themselves – but although they were unsuccessful these parties contributed considerably to what was becoming known about the Arctic.

So what sent these people up into the cold and lonely north for centuries, dating back to John Cabot in the 15th century and legendary figures like Martin Frobisher in the 16th century, Henry Hudson in the 17th and dozens of others?

In short, they were searching for the Northwest Passage, a route across the top of Canada between the North Atlantic and the Pacific. If they could find that route then vessels could make their way to Japan, China and the Spice Islands from Europe without the inconvenience of going around the treacherous Cape Horn or the long route around the bottom of the African continent at the Cape of Good Hope and then shore-hopping their way to Asia.

The route would cut the

time of shipping between New York and San Francisco . . . if such a

passage existed.

The route would cut the

time of shipping between New York and San Francisco . . . if such a

passage existed.

And that is why explorers from Britain, Europe and Scandinavia rugged up and headed into the largely unknown whiteness up there.

Some like Franklin and most on the ill-fated Greely Expedition of 1881 – only six of the 26 survived to report shipwreck, starvation, mutiny and cannibalism -- never returned.

But there are also heroes in Arctic exploration, among them many Norwegians who are honoured in the excellent Fram Museum on Bygdoy Peninsula a few minutes by boat across the fjord from central Oslo.

It is telling that not far from the Fram is also the remarkable Viking Ship Museum, further testament to the long history of sea-faring explorers and adventurers out of this region we know as Scandinavia.

The Fram Museum however –

a huge place with the actual vessel Fram (1892) which Roald Amundsen

took to the South Pole in 1911 but also went into the Arctic –

shines a spotlight on the heroic figures who are little known in the

South Pacific . . . because when they left home they headed north,

and then further north again into the bleak and cold unknown.

The Fram Museum however –

a huge place with the actual vessel Fram (1892) which Roald Amundsen

took to the South Pole in 1911 but also went into the Arctic –

shines a spotlight on the heroic figures who are little known in the

South Pacific . . . because when they left home they headed north,

and then further north again into the bleak and cold unknown.

It is ironic then that the mysterious disappearance of Franklin had fascinated the young Amundsen and he took it as his project in life to be an explorer. And he trained to be exactly that: He studied medicine at the insistence of his mother but after her death he dropped out and served as a mate on an 1897-99 expedition to Antarctica. He saw that if he could discover the location of the North Magnetic Pole – which had undoubtedly moved since it had been reached by James Clark Ross in 1831 – he would have the support of the Norwegian scientific community.

So he spent months in Germany learning about special scientific instruments and magnetism, got his skipper's ticket, bought a small but resilient fishing boat, the Gjoa, and trained as a seaman.

Then he recruited a small but intelligent and hardy crew of seasoned, multi-skilled professionals in navigation, meteorology, medicine and photography – as well a decent cook – and in June 1903 they departed from Kristiania (now Oslo) and headed towards Greenland.

There were near disasters – a grounding, a fire among other things –and terrible weather during which they had ditch some of their deck cargo. But in an area we now know as the top of eastern Canada they took shelter in a bay they named Gjoahaven and for two years – two years? – they conducted scientific experiments.

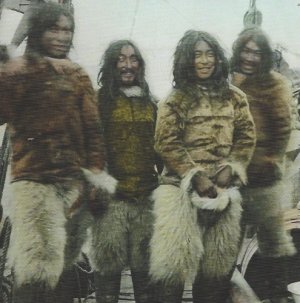

They encountered friendly

Inuits (“American Eskimos”), took many photographs of these hardy,

handsome and sometimes very beautiful people, and in August 1905

continued their journey across the northern seas.

They encountered friendly

Inuits (“American Eskimos”), took many photographs of these hardy,

handsome and sometimes very beautiful people, and in August 1905

continued their journey across the northern seas.

When they encountered a small whaler out of San Francisco north of Alaska they realised they could continue and successfully navigate the Northwest Passage.

They had spent three winters in the Arctic but in October reached San Francisco.

Amundsen and the crew returned home after three and a half years away, but the Gjoa didn't get back to Norway until '72 when it was shipped back by freighter and now rests at the Fram Museum.

At the Fram Museum the story of these remarkable heroes, explorers, scientists and sometimes ill-prepared adventurers are told, and the Fram itself – a wooden vessel which traveled further north and further south than any other – is there to be boarded and admired.

Amundsen's story did not end with his navigation of the Northwest Passage. As we know he was the first man to reach the South Pole in 1911. But just as remarkable and what proved to be even more dangerous was his attempt to reach the North Pole by flying boat in 1925-26.

With the American Lincoln Ellsworth and in two flying boats with four others, they flew further north than any previous flight . . . but lost contact with each other and when they landed they were miles apart.

Somehow they managed to meet up but one plane was so badly damaged it couldn't fly so the crew of six spent three weeks shovelling 600 tons of ice to make a runway . . . then all of them piled in the plane designed to carry just half their number.

When they finally got home everyone had assumed they had been lost somewhere in the white and watery wasteland.

In fact three years later

– after Amundsen had flown the first airship over the Arctic –

that is exactly what happened to him: While searching for survivors

of an airship crash, Amundsen's plane with its crew of five

disappeared somewhere into the sea in the remote Arctic Circle.

In fact three years later

– after Amundsen had flown the first airship over the Arctic –

that is exactly what happened to him: While searching for survivors

of an airship crash, Amundsen's plane with its crew of five

disappeared somewhere into the sea in the remote Arctic Circle.

That land, ice and the waters of the Arctic have, over the centuries, claimed many explorers and it seems strange to consider that somewhere out there, perhaps even frozen so solid as to still be recognisable, lies the body of a little fat man who took 1700 books and a pet monkey into that place . . . but inspired a man as remarkable as Roald Amundsen.

For more information on the Fram Museum in Oslo go to their website here.

post a comment