Graham Reid | | 9 min read

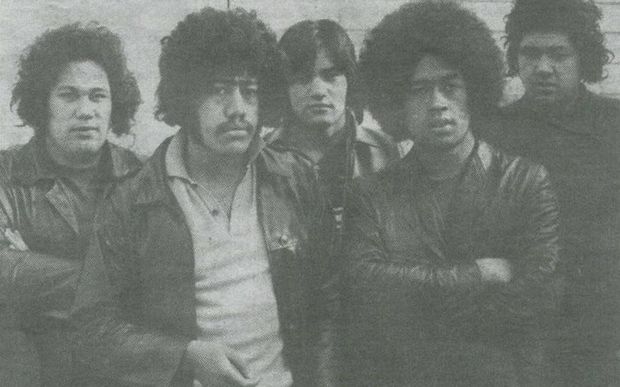

For anyone who lived through the period, the iconography and images still resonate: the clenched fists in leather gloves, the lines of civilian-soldiers in empowering uniforms of black polo-neck sweaters, impenetrable shades and black berets. The language was of black pride and the images defiant and confrontational.

The times they weren't a-changing, they'd changed - and in the early 70s righteous anger was galvanised into action as the peace and love of the late 60s disappeared like incense smoke.

In the new decade, revolution was in the air. And in bookshops, too, Bobby Seale's Seize the Time was a bestseller.

The Black Panthers, alongside Che Guevara, were poster art.

That, however, was the American experience, but their revolutionary rhetoric was inevitably imported into this country and took on its own distinctive character.

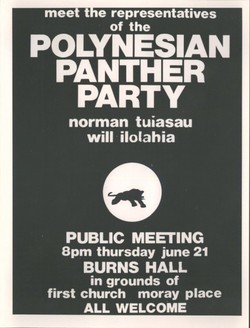

Thirty years ago this month the first meeting of what became the Polynesian Panther Party took place in an atmosphere where "you could cut the air with a machete," says Ta Iuli, at the time a schoolboy at Mt Albert Grammar and later to become Minister of Information in the PPP.

Today among former Polynesian Panthers

are a chaplain, musicians, a university lecturer, an international

chef and numerous social workers. Many speak of being in the PPP,

when most were teenagers, as a formative experience of their lives.

Today among former Polynesian Panthers

are a chaplain, musicians, a university lecturer, an international

chef and numerous social workers. Many speak of being in the PPP,

when most were teenagers, as a formative experience of their lives.

During the turbulent 70s, when dawn raids were made on the homes of suspected overstayers (the PPP did dawn raids on the homes of politicians by way of reply), the occupation of Bastion Pt and then in 81 the Springbok tour protests, the Polynesian Panthers were a visible part of the activism of the age.

At its peak the party had around 500 members and chapters in all the major centres, but membership dwindled as some left to take up family obligations, and there were also bitter internecine arguments. Some still feel the deep divisions of those personality clashes which came in that crucible of passion and politics where egos and aspirations rubbed against each other.

Last weekend more than 50 former members and their families gathered in Auckland to commemorate the party's founding, although there were some notable absences.

"Some people just didn't want to remember because it affected them that much," says Will 'Ilolahia, one of the founders of the party which emerged as a breakaway group from a loose affiliation of central city Maori and Pacific Island street gangs gathered under the banner of the Black Panthers.

Recently there has been some reinvestigation of the role the Polynesian Panthers played in changing the social climate and self-perception of young Pacific Islanders in the early 70s, most notably in a 1998 thesis by Michael Fonoti Satele entitled The Polynesian Panthers: An Assertion of ethnic and cultural identities through activism in Auckland during the 1970s.

Those interviewed for Satele's thesis

speak of the pride and purpose the movement gave them, of the better

understanding of their Polynesian brothers and sisters they gained by

being part of it.

Those interviewed for Satele's thesis

speak of the pride and purpose the movement gave them, of the better

understanding of their Polynesian brothers and sisters they gained by

being part of it.

The Polynesian Panthers were founded at a tense meeting on June 16 in Keppel St, Ponsonby, where 'Ilolahia and Fred Schmidt convinced members of the Black Panthers to strike out on their own path modelled on the ethos of their Stateside mentors.

A former member of the inner-city gang Niggs, 'Ilolahia would helm the Polynesian Panthers as chairman for five years - after a short stint by seaman Schmidt - and help to write a significant, but largely ignored, chapter into Pacific Island politics and race relations in New Zealand.

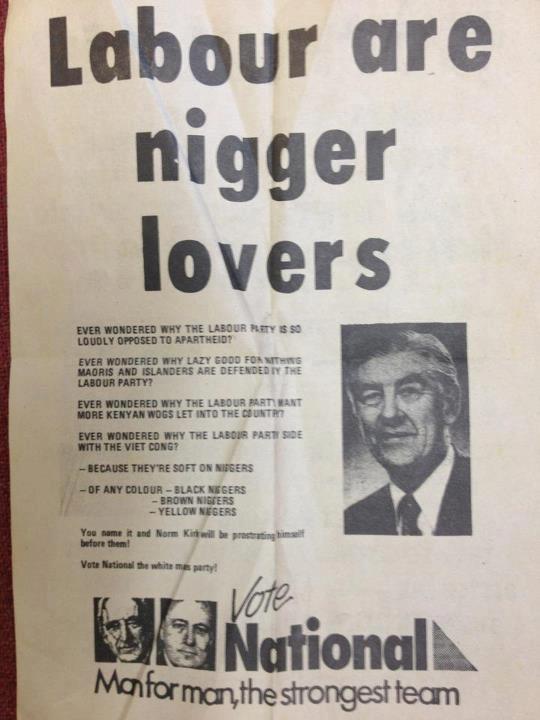

In his thesis Satele includes a telling quote from Tom Newnham, then a school teacher and secretary of the Citizens Association for Racial Equality (Care), an organisation which shared facilities, and sometimes aims, with the Polynesian Panthers.

It reminds of the social climate from which the PPP sprang.

"It was practice," says Newnham, "on every occasion there was a reported crime, major or minor, in the vicinity that the police would 'cruise' the area and grab every teenage Polynesian boy and take him to the police station for 'questioning.' That was the atmosphere that leads to the Panthers 'taking a stand'."

"It was an era of the hope of change," recalls former Polynesian Panther Wayne Toleafoa, who joined the movement at 16 for two years and today is a navy chaplain. "You had the Progressive Youth Movement and Tim Shadbolt, and Nga Tamatoa from the Maori side. There was a lot of idealism around at the time.

"It was a society that denied

there was any racial prejudice at the time, but we experienced names

like 'niggers.' We thought it didn't match with a racially

prejudice-free country."

"It was a society that denied

there was any racial prejudice at the time, but we experienced names

like 'niggers.' We thought it didn't match with a racially

prejudice-free country."

Former PPP members note they were also the first generation of Pacific Islanders who would deny the mores of their cultures and speak up where their elders preferred a dignified silence.

"Polynesian people are very passive and we don't go to city council and knock on their door," says thesis writer Satele. "What I concluded was this [Panther movement] was positive because here were these young people actually doing something about injustice. A lot were doing this with the disapproval of their parents and going against their culture."

The PPP were outspoken and visible, quite often alienated their elders and certainly - in the berets, shades and black uniform adopted from the Stateside model - appeared a threat to white middle-class New Zealand.

"We had nothing but ourselves, our camaraderie and our solidarity, when we founded the Polynesian Panthers," wrote Iuli to 'Ilolahia last week. "For us the most important mission was to galvanise and unite all the Polynesian youth; Maori, Tongan, Samoan, Rarotongan, Niuean, Tokelauan, Fijian and our sympathisers under one voice. We desperately needed to speak out, to challenge where our elders and leaders had tried to remain silent.

"New Zealand was still in the colonial dark ages as far as social conscience was concerned and most New Zealanders were in self-denial when racial discrimination against 'boongas' and the natives was ever mentioned."

Auckland's social geography was very different 30 years ago. Large parts of Ponsonby and Grey Lynn were predominantly Maori and Pacific Island. Extended families were often crowded into traditional villas and many of the kids ran in loose street gangs.

'Ilolahia was a gang member while still at Mt Albert Grammar: "We weren't patched members, just groups of guys hanging around. There was a skirmish with the Hells Angels down at the speedway, that sort of thing."

But, fuelled by the ideologies from America which he was hearing in his first year at university, 'Ilolahia and others looked to their own environment.

"It became politicised to the extent we had liaisons with the Panthers in States - one member went up. But we had this stigma we were a street gang of heavy-looking dudes, so we did things thing like taking old people out on bus trips, painting houses and delivering the community newspaper [City News].

"We did things like that to try and kill that image. Then we started to confront the problems our people faced so we set up the TAB, the Tenants Aid Brigade, which would surround certain houses where tenants had a problem with the landlord."

With Care, the PPP also established homework centres, and linked with the Peoples' Union to set up a food cooperative. It raised money for causes with which it sympathised, was prominent in the anti-Vietnam protests, and organised a bus to take families and visitors to Paremoremo Prison where they also had a chapter. Former inmates were also given advice, assistance and often accommodation with Panthers on their release.

They established the Pig Patrol, Police Investigations Group which followed police task force units and watched for incidents of confrontation with Pacific Islanders and Maori. Members of the Pig Patrol were some of the biggest guys in the PPP but they were also schooled in how to avoid confrontation. They would inform those hassled or detained by the police of their legal rights.

Toleafoa, who ironically joined the police for six years from 1980 before finishing theological studies, remembers "as a schoolboy being called upon to do very adult things, when basically you were just a kid."

The PPP produced 1500 copies of a legal aid booklet authored by David Lange, who was their legal adviser. It also attempted dialogue with nascent Maori nationalist movements, arguing the dominant European culture was trying to divide Maori and Polynesians.

The movement's rules were simple and strict: no possession of narcotics or being under the influence of alcohol during movement time; no possession of weapons or harmful devices; no using the name of the movement in public for self-glory; equality of the sexes.

In much of what they did, the Panthers were ahead of their time. What many former members are most proud of is the homework centres because they prevented kids from sliding down the path they had been on.

"At that stage there weren't too many organisations in our [Pacific Island] community that weren't aligned to the church," says 'Ilolahia. "We were probably the first youth organisation that did a lot of social things, and consequently also had a lot of female members.

"Because in our society then girls had to stay at home and get permission to go out, they came from a different sector of our community. In hindsight there were a lot of things happening among the women we weren't aware of."

'Ilolahia concedes that while they were for gender equity, "looking back we were pretty sexist, it was the Island way that men would take the lead."

Etta Schmidt, now a caregiver at her local school in Whenuapai, sister of co-founder Fred and only 17 when she attended the inaugural meeting 30 years ago, remembers it slightly differently. "What drew me into it was the movement was there to help the greater Polynesian group in the area, especially the youth. We were proud we belonged because we were able to help out in the community.

"The ladies there felt they were pretty functional in regards to helping out, we weren't there to boost boys' egos, that's for sure. [Will] probably did have young ladies there to boost his ego and he may have relished that, and also some of the other men, but we were there to be part of the cause."

The PPP in Auckland was divided into two chapters, one in the central city and another in South Auckland headed by Aorere College student Vic Tamati who, because he was a schoolboy, found it hard to be taken seriously by the police J-team with whom he wanted to work on youth projects. And even more so by local gangs. So where the city chapter deliberately targeted gangs for members, Tamati had to adopt a different approach.

"I couldn't change those older guys, they were lock and load on where they were. My thinking was to encourage the young ones to look at the way they were living. I wanted to change the future, not the present, and that's where Will and I differed. He wanted me to bring in the fighters."

But South Auckland gangs thought the PPP was just another street gang from central Auckland out to take their patch. Tamati says he was fighting so often he felt he was moving into that lifestyle rather than away from it.

"So no, we didn't get our point across. South Auckland was fast growing to be a Once Were Warriors place. Everyone around me was either joining the Black Power or the Mongrel Mob and I was trying to say, 'Let's go political.'

He recalls his Panther years in South Auckland as "much harder than Will could ever have imagined."

Will 'Ilolahia was an unlikely candidate to head the Polynesian Panthers. His mother was from the noble class in Tonga and his father, Molimea 'Ilolahia, was butler to governors-general for almost four decades and served the Queen on her royal visits around the Pacific.

'Ilolahia was a prefect at Mt Albert Grammar and by the mid-70s, while a Panther, graduated with a degree in sociology and anthropology from the University of Auckland. He'd completed his study while serving time for assault.

After drifting away from the Panthers because of family and work commitments, he became the social welfare and recreation officer for One Tree Hill Borough Council, was a detached youth worker, won a commonwealth fellowship to Hong Kong to study youth at risk in the late 70s, and managed Herbs.

As with many former Panthers, he was active during Bastion Pt and anti-Springbok protests in 81 and, after a two-year court case relating to anti-tour activities, went back to Tonga. He returned to New Zealand a decade ago to look after his mother after his father's death. Today he is a father of seven, works for a communications company, and still has the music and arts trust he founded when he managed Herbs.

He, like some other Panthers, believes there is a need for a contemporary equivalent of the Panthers. Who is telling our people not to waste their money in the casino, he asks rhetorically. And who is raising health issues within the communities? "That was the thing about us, we talked to our own people as much as we did anything. That was one of the most important things we did."

Last weekend former Panthers and friends, extended families and former foes talked among themselves again. At their reunion other issues were also discussed, particularly plans for a book and film to document the movement. And some old animosities were resolved.

One who left the Panthers in disgust, in part over disagreements with 'Ilolahia, was there. Former South Auckland PPP chairman Tamati came up from the South Island, where he has long been a youth worker, because what he believed back then hasn't changed.

"I've always perpetrated that message, and the image we gave of the panther was it was a docile animal. It lives, it feeds and sits in trees and enjoys life. But corner a panther and you've got a whole different beast, it comes out on the offensive.

"I've always operated that same psychological and mental attitude in everything I do. I'll work with your systems, I'll work with you. But don't put me or my people down - because I'll come out fighting."

post a comment