Graham Reid | | 4 min read

About 140 years ago when Thomas Edison made a machine which captured sound he initially thought it could preserve the grand statements and speeches of great men.

But he quickly realised – even before his phonograph which used wax-coated cylinders was made available – here was how music could be passed down the generations, the past always present in the future.

Edison wasn't alone in pursuing the idea – a decade later Emile Berliner created flat discs which became omnipresent – but the technology changed the art.

As British writer Peter Doggett noted in Electric Shock; From the Gramophone to the iPhone; 125 Years of Pop Music, “The invention of recorded sound transformed music from an experience into an artefact . . . it allowed for endless repetition of what would once have been a unique performance”.

A century ago the gramophone and wireless began to replace the piano in the living room.

Oddly enough, in the 30s and 40s many artists – notably black American blues performers paid a flat fee for a recording – didn't see record sales as the income earner. A popular record meant they could command higher performance fees, they made their money on the road.

But many 60s pop artists realised how record sales (and publishing) could be a major income. Paul McCartney admits that in the Beatles' early days he and John Lennon would say, “Let's write a swimming pool”. A hit record could give them that, and more.

By the 70s and peaking in the 80s, income from record sales could be astonishing: by his own account Mick Fleetwood hoovered up millions of dollars worth of cocaine because album sales for Fleetwood Mac (in 75) and Rumours (77) – around 50 million in total – allowed him that luxury.

Then there was touring money.

Peter Frampton's 75 Frampton album barely made a ripple but he won an audience on the road – just as blues artists had done decades before – and his double Frampton Comes Alive the following year clocked up more than 10 million in sales.

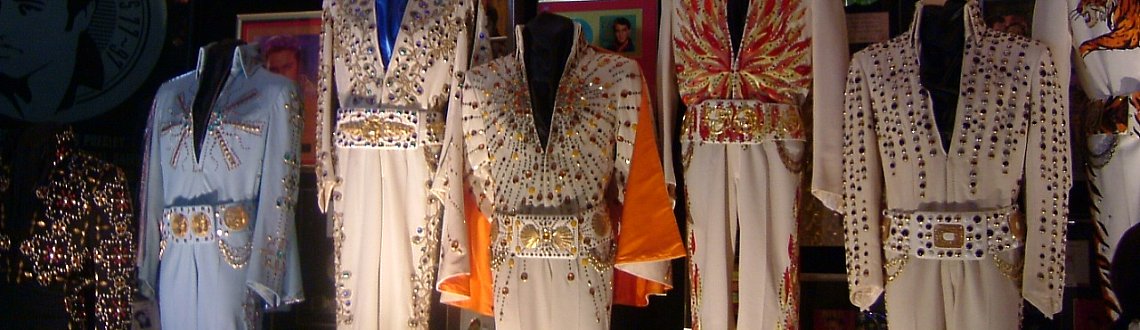

Recording and touring was the marriage made in fiscal heaven, in the 90s merch (merchandise like t-shirts, keychain, programmes, bags and tat) added another revenue stream.

But the wheel spun and the times changed.

If CDs had given second wind to music sales through reissues and the excitement of a new technology, something lurked beyond the horizon: the internet.

The launch of Napster in mid '99 – which allowed file sharing between users – meant the marketplace became a free-for-all and recorded music was increasingly free for all.

Napster was shut down but the wheel was still in spin and then . . . Spotify.

Sales of CDs and downloads ground to halt but because Spotify, the controversial Tidal and other streaming services don't equate to any substantial financial return, artists – from Madonna to your local garageband – had to tour, get the merch out and stay on the road.

The well-publicised and much streamed album or single, as in the 30s and 40s, simply raised the profile for concerts.

And now that has ended abruptly.

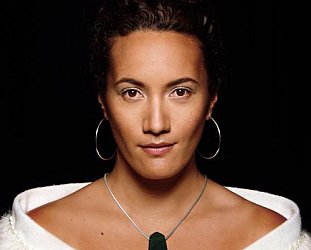

International tours by New Zealand artists such as Nadia Reid (to SXSW in Austin), Tami Neilson (European dates), the Beths (across the US) and others are on hold or being rescheduled, and locals – such as Th'Dudes who had a reunion tour scheduled – are now house-bound.

The wheel has, for a while, stopped spinning.

The wheel has, for a while, stopped spinning.

Ironically the technology which knee-capped music sales is invaluable for musicians in isolation: possibilities include live or recorded streaming of performances at home; chatroom contact with fans; simulcasts involving artists in separate locations; podcasts, playlists and quirky at-home videos to keep the profile and audience interest high; social media platforms to connect with that invisible fanbase which will be sympathetic and curious . . .

A solo version of Neil Finn's Out of Silence orchestrated project is entirely possible from a musician's home studio which can pull out a string section at the flick of a programme button.

Monetising these things is, of course, the difficulty.

These may be challenging times but they can also present opportunities for lateral thinkers.

Websites like bandcamp and soundcloud allow artists to curate their art and if their music is bought – often at ridiculously low prices – artists could continue to make a modest income.

But younger musicians who have barely established an audience now can't build one through touring and will suffer the most. Many could understandably feel cheated and angry. The promise of a creative career snatched from them for the foreseeable future.

Some will get depressed, and worse.

New Zealand has a unique 24-hour support line for musicians and those in the industry in need of help, guidance and counseling. The MusicHelps Wellbeing Service was established in 2012 and undertook a self-selecting survey of the mental and physical health of musicians in 2016.

The results were extremely worrying: Over a third of songwriters, composers and performers reported they'd been diagnosed with a mental health disorder (almost twice that of the general population), and twice as many in that group as opposed to the general population reported having attempted suicide . . .

It got worse: 84% of respondents said they'd experienced such stress in the preceding year that it affected their ability to function; songwriters/composers were two and half times more likely to have been diagnosed with depression than in general population . . .

That was then. But now, as never before, local musicians need MusicHelps which offers individual guidance as well as supporting community programmes.

In addition to assisting local artists survive by buying their music or merch, anyone can donate to MusicHelps which has just extended its service to the broader arts communities.

More than half a century ago a young troubadour sang, “the wheel's still in spin and there's no tellin' who that it's namin', for the loser now will be later to win . . .”

The times can't change fast enough for some.

MUSIC HELPS; AWHINA PUORO

Toll free 0508MUSICHELP

post a comment