Graham Reid | | 2 min read

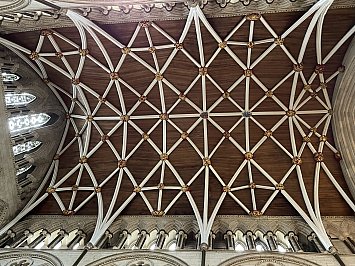

In a museum deep below the soaring Gothic majesty of Yorkminster, down where the pillars of the Roman garrison fort in York are still visible, there are remarkable objects on display.

Among them a horn from about 1030 presented by the Viking nobleman Ulf to the Christian church as a symbol of his gift of lands. It also represents an extraordinary confluence of cultures. The horn is carved from an elephant’s tusk and was made in southern Italy, possibly the port city of Amalfi which was trading with the merchants of York. And the carvings on it are images of lions and deer copied from Babylonian and Sumerian art.

Here too are the York Gospels from around the same period, the only book from before the Norman Conquests to survive at Yorkminister.

These are extraordinary things and reward time spent with them.

If there’s an upside to traveling through Britain in the time of Covid it’s that you’ll be untroubled by other tourists.

In the past two months I’ve only heard two American accents, a half dozen from Eastern Europe and just a couple from Japan and China.

Antipodeans? Not one.

Britons in hospitality are delighted to see you – most travellers we’ve encountered have come from somewhere else around Britain – and happy to chat.

Bristol, Bath and Liverpool were busy, but not as much as they might otherwise be – at the excellent Beatles Story museum in Liverpool I could sociallydistance without any trouble – but smaller places like Cirencester and Shrewsbury were almost empty, bar locals.

This means no queues, not in Bath to see the Roman ruins or at jaw-dropping Castle Howard (famous from the television series Brideshead Revisited). At Lindisfarne, a tourist magnet which will undoubtably draw bigger numbers when summer comes, you could take photographs without a living soul in them.

Crossing into Scotland has meant even fewer visitors in the villages and townsbut also a renewed concern about Covid.

Scotland’s cases are going up faster than south of the border and The Scotsmanreports A&E departments facing a “patient safety crisis” with the Royal College of Emergency Medicine estimating that 36 Scots died in the previous week as “a direct result of avoidable delays”.

We’ve come to a country where the mandate on masks in many places -- public transport, places of worship, workplaces, shops, bars and clubs – has just been extended. With very little discernible complaint and considerable compliance.

I suspect many will continue the practice.

The Royal College of Nursing talks of a crisis because of staff vacancies and wait times for cancer treatment are at the worst level on record according to a support group.

Then there’s galloping inflation.

That said, we’re loving beautiful Scotland, the country I was born in but have only been back to four times prior to this trip.

And what we’ve observed here too is the outpouring of support for Ukraine in crisis.

In North Berwick the statue of a man with binoculars looking out to sea has a crocheted blue and yellow heart hung around his neck, there’s an installation of a tear falling from a blue and yellow eye projected on a white wall near our little hotel and at the Ship Inn they are donating 50p (about 95 cents) from every pint of “Ukraine Independence” beer sold to the Red Cross’ Ukraine fund.

The world has always been smaller and more interconnected than we often think – as that Viking horn demonstrates – and in Scotland, despite problems of its own, hearts still go out to those in more dire circumstances.

These may seem small and symbolic gestures but, amidst the clatter of war and the torment of suffering, they speak of the best in human nature.

.

For other articles in this series go here.

post a comment