Graham Reid | | 3 min read

“In and out on the same day,” the guy in uniform at Peterhead Prison said to me. “That's rare.”

No doubt it's a joke he'd used on visitors before, but it's a good one if you only hear it once.

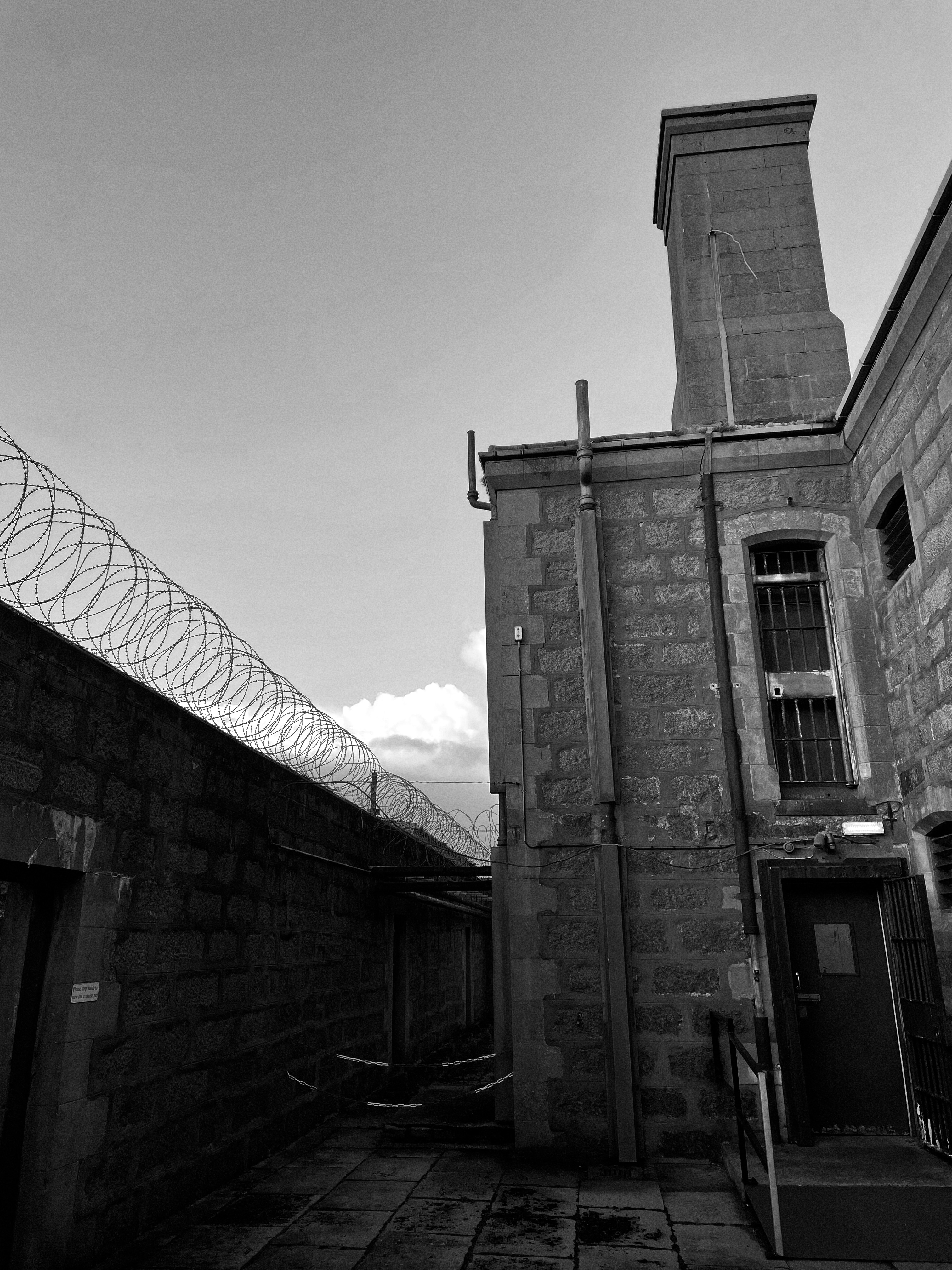

Peterhead Prison on the stormy coast of Scotland north of Aberdeen is a forbidding fortress and was in operation right up to 2013.

It's in a cold place and you can imagine how violent it must have been when you learn it was where “the hardest men in Scotland” were sent.

It was the place where hope went to die, or at least serve out its sentence.

It was the place where hope went to die, or at least serve out its sentence.

These days it is preserved as a museum, a living reminder of the grim conditions the men endured.

Opened in 1888, Peterhead was the epitome of Victorian austerity and punishment: cells were small with a hammock and a pail for shitting in; nourishment was meagre and exercise restricted to half an hour a day.

The men were here to be punished not reformed.

Over the decades there were modest changes (a bed replaced the hammock) but it was never less than dismal and dangerous.

And the population grew to double the planned-for capacity in the years before World War 1.

Right into the 21st century prisoners would line up every morning to empty their overnight buckets of waste in a central toilet and shower area.

Right into the 21st century prisoners would line up every morning to empty their overnight buckets of waste in a central toilet and shower area.

Fights were common and you don't need much imagination to picture that scene.

Today on a tour of the facilities you are confronted by the stark reality of what life must have been like for those locked up here.

On the day we went around – a cold day just before Christmas – we were the only visitors. It felt even more inhospitable and chilling.

Around the walls photographs tell of the inmates working the nearby quarry (under armed guard) to built the huge breakwater in the harbour.

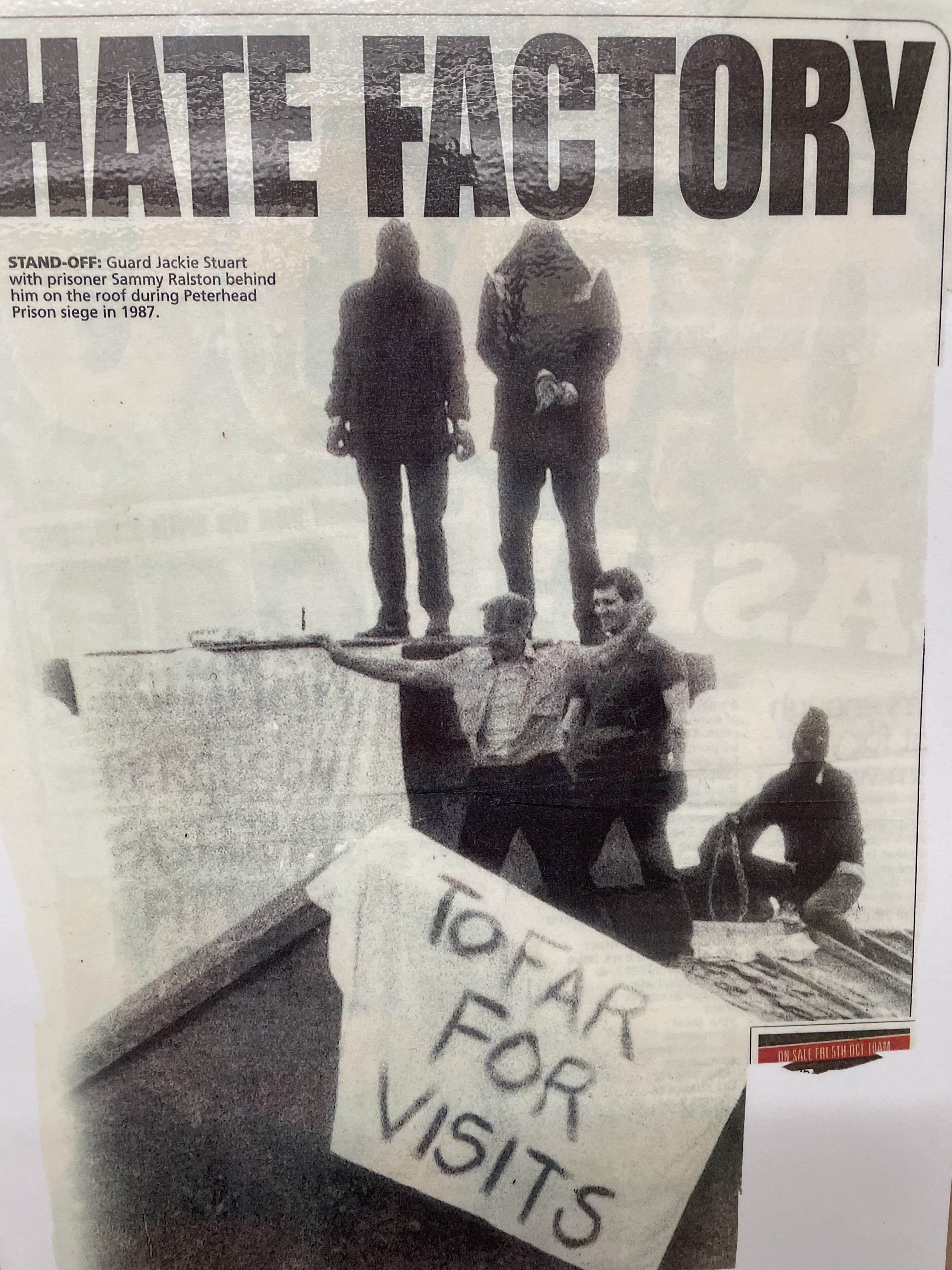

And of the 1987 riot in which an officer, Jackie Stuart, was taken hostage and how prisoners smashed their cells, the toilet block and kitchen . . . Anything they could.

The SAS were brought in to end it.

The SAS were brought in to end it.

There were also “dirty protests” where prisoners smeared their excrement on the walls of their cell. One room replicates that.

It's a bleak place full of silent echoes of pain and caged anger.

However there's also the story of recidivist Johnny Ramensky who was brought into an elite Commando unit of World War II headed by Sir Ian Fleming, the James Bond author.

Ramensky's skills were safe-blowing and lock-picking – which had seen him inside Peterhead repeatedly – and during the war he was part of secret sabotage missions in Europe. It was his special talent which saw him back behind bars in Peterhead when the war was over.

Needless to say he was also skilled at escaping.

Needless to say he was also skilled at escaping.

It was the only vaguely amusing story in the place.

Even the mannequins of inmates looked ferocious.

Then right at the end of these halls of horror was the worst of it: The Silent Cell.

Here was a small space between concrete walls so thick no sound from the outside world could be heard by the unfortunate.

And his shouts, screams, wails and sobbing couldn't be heard by those outside.

It was the most disturbing room of them all.

So moving, that we skipped going to the hospital wing.

We left this cold place of misery, violence and the graveyard of hope, and began a long, silent walk back to the carpark.

We left this cold place of misery, violence and the graveyard of hope, and began a long, silent walk back to the carpark.

It had been an informative if harrowing experience.

And then the wind off the turbulent North Sea whipped up and a biting, horizontal hail slashed at us, the empty courtyard and the walls of this public and private hell.

It seemed appropriate.

.

.

For more information on tours of Peterhead Prison go to www.PeterheadPrisonMuseum.com where it is billed as a "one of a kind wedding venue".

post a comment