Graham Reid | | 2 min read

There are many things you can expect at the famous Bako National Park in Sarawak, some 40 minutes from the capital Kuching by car then a small boat across the river. At Bako you could expect proboscis monkeys, biting ants the length of half a matchstick, the Borneo bearded pigs which are so solid you feel you could throw a saddle on them, poisonous snakes, vibrant blue skipper mud crabs in the mangroves . . . All to be expected.

A conversation about the French writer Camus certainly wasn’t what I anticipated however.

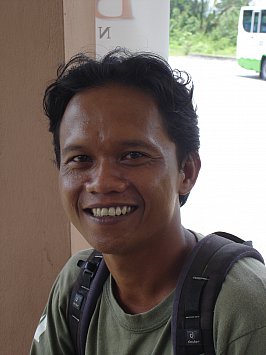

I hadn’t taken into account my guide for the day Riman who was an articulate, scholarly, impossibly young-looking 31-year old from the local village.

“Oh yes, I like Camus. His Resistance, Rebellion and Death and of course The Stranger. I read many such writers. But I am not so keen on Shakespeare. His stories always seem so improbable to me.”

And so there in sweltering humidity against a backdrop of dense, lush tropical jungle Riman and I briefly talked literature, how he was largely self-educated from borrowing the European classics from the local library, and how so many of the young people from his hometown -- a fishing village where some homes on stilts stood over the muddy river -- could speak excellent English.

Much as you do, I wanted to say.

“But many of the local boys maybe just get into fishing like their families, or work for the timber companies which clear the jungle. It is such a waste,” he said.

And so the conversation turned to conservation, about which he was equally passionate and well-informed.

Riman had been an official park guide employed by a tourism company for the past eight years and now took individuals, and groups of German, English, Italian and Arab visitors to Sarawak on day trips or overnight stays in the jungle he grew up in.

Even now he and his friends would still just go into Bako for their own pleasure.

“We used to play in here as boys, but now of course when we come out here our conversations are different. We talk politics and conservation.”

But probably not Camus, or the Irish writers like James Joyce whom he also counted among his favourites.

Over the course of a day -- during which my light silk shirt turned into a saturated body-clinging mess and he barely broke a sweat -- we walked a small section of the jungle and his keen eyes pointed out that poisonous snake on a nearby branch (it took me a full minute to spot it) and proboscis monkeys high in the trees.

Later we sat and watched a young male proboscis no more than two metres away and which he was concerned about.

“I have seen him before, I think he has been abandoned by the group.”

Then later the dominant male -- a surprisingly large animal with a thick tail akin to that of a wallaby -- came down to the mangrove swamp followed by half a dozen females and offspring. It was a rare and remarkable sight.

When we took the longboat back to the village Riman chatted about the various virtues (or otherwise) of the tourists he took around Bako. (I won’t embarrass a whole European nation by naming and shaming.)

I gave him my card as I waited for lift back to Kuching.

He look at it ands his eyes lit up: “You write about music too?”

I explained the years spent with rock bands.

“Can I send you some music I make with my friends?”

I said of course, that I’d love to hear it.

“It’s death metal, you know ‘uuuurrrghh’,” he said making the sound of Satan bellowing from a fiery pit. “But we also put in some local flavours.”

I said, quite genuinely, that I’d love to hear it and I hoped he would e-mail me some songs. He promised he would.

And so we shook hands by the muddy brown river and I went back to Kuching for a shower and he went back to his fishing village in the shadow of the jungle to do some paperwork.

Camus, James Joyce and Malay-style death metal?

Not quite what I expected when I went to look for the rare proboscis monkeys at Bako National Park.

post a comment