Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Give

them credit, they were persistent.

When the

Reverend Thomas Baker, a Methodist minister, unintentionally insulted

a chief on the Fijian island of Viti Levu in 1867, he and six of his

Fijian followers were hacked to death and eaten.

Baker

has the dubious honour of being the only European Methodist to be

dispatched in such a way.

And the

people didn't stop with him. The story goes they also tried to eat

his boots, bits of one being on display in the Fiji Museum just 10

minutes walk from downtown Suva.

Here is

a glass case you may also see Rev. Baker's Bible,

the bowl he was served up in and a large wooden fork.

Suva's

small but fascinating museum offers an insight into many and often

confusing aspects of Fiji's social, religious and political history,

among them that 19th

century missionaries spread the idea Fijians were descended from

Egyptians. This lead to a local paper in 1892 telling of the journey

from Thebes up the Nile to Lake Tanganyika and then on to Fiji in the

Kaunitoni canoe.

There

are many such marginalia in the museum but the visitor is greeted on

entry by the impressive out-rigger Ratu Finau -- “the last Waqa

Drua” (ocean-going canoe) – of 1913 which has a main hull 13.4m

long and massive steering oars which needed four men – four Fijian

men, remember – to operate.

This, we

are told, “is a relatively small canoe in comparison to those from

the 1800s”.

The

museum not only offers artefacts such as 3000 year old Lapita pottery

and distilled history (how the population fell from 250,000 to just

85,000 between 1800 and 1921 through the ravages of imported European

diseases), but oddities of specific interest to the New Zealand

visitor.

Here is

a 1991 wedding dress made of masi (tapa) by New Zealander designer

Annie Bonza, and Maori designs are incorporated into Fijian carving.

Then

there is the bamboo fishtrap which coincidentally looks like a

vuvuzela and is called a “vuvu”.

A day in

the Fiji Museum is one well spent, and just getting there is an

interesting walk from downtown cosmopolitan Suva and its multi-ethnic

shops, traffic (not as laid back as the stately walking pace of its

citizens) and jigsaw of architecture from handsome colonial to odd

Art Deco and 70s embarrassments.

The

museum is located in Thurston Garden with a large clocktower

dedicated to the first mayor of Suva G.J. Marks who was drowned in

the St Lawrence River, Canada in 1914 when the SS

Empress of Ireland sank.

The

garden, a steamy blend of unconstrained tropical growth and manicured

areas, is a perfect place to take some time out of sprawling Suva

which has a population in the greater area of around 500,000.

And it

is opposite the playing fields of Albert Park.

If World

Cup football matches are won in the academies of Europe, then the

Rugby Sevens' training ground is a place like Albert Park where

athletic schoolboys bail out of the back of a truck, sing a hymn then

play finger-tip, passing rugby at great speed, with slamming body

contact and no time wasted for injury stoppages. It is something to

see.

I asked

if I could look inside, was waved on with a smile, and the young

soldier accompanying me and I bemoaned its condition as we stood in

the grand hall looking at the blue ocean beyond.

The

presence of soldiers reminds you that despite the business-as-usual

all around you, politics is inescapable in any discussion of

present-day Fiji.

But here

the museum is also useful in that it offers the long view of Fiji's

troubled history since the early colonial period.

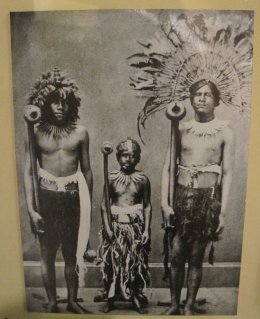

There

you may read of the Kingdom of Fiji and the short-lived Cakobau

Government (1871-74) which printed its own paper money in the years

before the country became a British colony; of the shameful

“blackbirding” (coercing or kidnapping of people from other

islands, notably the Solomons, to work on plantations); of the dwarf

priest (pictured left with two warriors and the pickled arm of a slain

chief) who was sold to Barnum, Coup and Costello's American circus to

raise funds for the government in the late 19th

century; of the indentured labourers from India (the practice only

officially ended 100 years ago) . . .

There

you may read of the Kingdom of Fiji and the short-lived Cakobau

Government (1871-74) which printed its own paper money in the years

before the country became a British colony; of the shameful

“blackbirding” (coercing or kidnapping of people from other

islands, notably the Solomons, to work on plantations); of the dwarf

priest (pictured left with two warriors and the pickled arm of a slain

chief) who was sold to Barnum, Coup and Costello's American circus to

raise funds for the government in the late 19th

century; of the indentured labourers from India (the practice only

officially ended 100 years ago) . . .

And of

Moy Bak Ling (pictured with his extended family) who went from Duan

Feng in China to the Australian goldfields as a 17-year old but fled

the appalling conditions three years later and sailed solo to Levuka

in 1855. His carpentry shop was the first Chinese business

established in Fiji.

Today, a

kilometre or so from the museum, the Chinese government is building

an enormous new embassy behind towering walls and using labourers

brought in from the mainland.

The

flags of China, Taiwan and Korea wave over aid projects, the

Americans have an equally large embassy and visible presence.

Politics

is everywhere and visitors will make what they will of it as daily

life goes on, although aspects of the unhappy past inevitably inform

the present.

So the

museum is not the only place you can feel Fiji's complex story. You

can see it reflected in something as simple as shopfronts in Suva,

such as the old Regal on Victoria Parade which, in what must have

been a cinema with a suggestion of Art Deco in its graceful curves,

now houses a Pizza Express, a cake shop and the Capital Palace

Chinese restaurant.

So the

museum is not the only place you can feel Fiji's complex story. You

can see it reflected in something as simple as shopfronts in Suva,

such as the old Regal on Victoria Parade which, in what must have

been a cinema with a suggestion of Art Deco in its graceful curves,

now houses a Pizza Express, a cake shop and the Capital Palace

Chinese restaurant.

It is

right next to a McDonalds on the edge of Ratu Sukuna Park.

In that

one small corner of downtown Suva you can read the names and feel

something of the complex, interlocked past and present of this

interesting city.

For other travel stories by Graham Reid, see here for his two award-winning travel books.

post a comment