Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Dropkick Murphys: Peg O' My Heart

The

black and white image of the man on the small television screen looks

like something from a remote world of more than a century ago:

wearing a white shirt, braces to hold up wide flannel pants and heavy

work boots, he shaves timber slats into shape, arranges them

carefully and then hammers an iron hoop around them.

Against

the backdrop of a factory where steam wheezes from huge machinery,

the man labours with remarkable physicality, speed and skill.

He

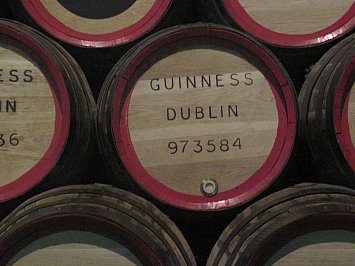

is Dick Flanagan who was a cooper, and here at the famous Guinness

Storehouse in Dublin’s St James’ Gate Brewery -- home to the

company which this year is celebrating its 250th

anniversary -- he plied his craft. But these ancient-looking images

came from as recently as 1954 when Guinness was still keeping their

liquid black gold in wooden casks.

At

one time there were 300 coopers working fulltime making casks for

Guinness and the storehouse complex contained over quarter of a

million of them, all made by hand where the craftsman’s eye was the

measure.

At

one time there were 300 coopers working fulltime making casks for

Guinness and the storehouse complex contained over quarter of a

million of them, all made by hand where the craftsman’s eye was the

measure.

To

watch Flanagan is captivating: he shapes slats with a small adze-like

chisel, pulls them together so they are airtight and then moves on to

making, then hammering down, the iron bands. Then, for the first time

using any measuring gear, he takes a ruler to size timber for the

tops and bottoms which fit snugly.

On

a day when a Guinness awaits in the Gravity Bar on the top floor of

the Storehouse -- the seven-storey building in the shape of a glass

of Guinness with the bar as its head -- no one on the self-guided

walk through the brewing process seems to be in any hurry.

Flanagan

finishes his cask and the film loops to begin again, mirroring

exactly what his working day was for decades.

A

visit to the Guinness factory is a highlight of any trip to Dublin

because if nothing else, and there is plenty of the “else” for

your interest, you get a spectacular 360 degree view over the city

from the Gravity Bar as you sup a pint which comes with the price of

your admission.

The

Guinness story is a fable of good fortune and canny business smarts:

Arthur Guinness (1725-1803) signed the lease on the abandoned St

James’s Gate Brewery on 31 December 1759. It was for 9000 years at

an annual rent of 45 pounds: a copy of this remarkable document is

embedded in the ground floor of the Storehouse.

Within

a decade he was exporting his ale, in 1770 he began developing a

higher quality “porter“ (the forerunner to Guinness), and by 1799

he had stopped making traditional beer. His expanding brewery was

solely dedicated to his refined “porter”, known now across the

world simply as Guinness.

As

with any decent whisky distillery, Guinness claims one of its key

ingredients is the special water it uses which is not, as rumour has

it, taken from the River Liffey but comes down (eight million litres

a day of it) from the nearby Wicklow Mountains. To the other

ingredients -- barley, hops and yeast -- was added the most

important: Arthur Guinness, the son of a brewer and a man who knew

how to market his product.

His

canny know-how is a trait the family carried on and in the Storehouse

is a large area dedicated to the clever advertising campaigns

Guinness has run, and the memorable advertising imagery (toucans,

ostriches, surfers) from the pen of graphic artist John Gilroy who

created the Guinness marque for three decades from the 30s.

Gilroy,

who created the famous “Guinness is good for you” poster among

many others, was also a gifted portrait painter who subjects included

Sir Winston Churchill, Sir John Gielgud and the Queen, whom he

painted when he was 82.

Today

10 million glasses of Guinness are drunk daily in places as far apart

as India and Indiana. It is brewed in more than 40 countries and sold

in over 150.

The

Storehouse is billed as the number one tourist attraction for

international visitors in Ireland and is an easy 20 minute walk from

the central city, and a stop on the hop on-hop off bus tours.

The

view of the city -- with landmarks identified -- from the Gravity Bar

is worth the visit alone, made more pleasurable by a glass of

Guinness.

But

while the Gilroy posters will attract the eye and hops assail the

sense of smell, for many visitors crowding around the screens, the

sight of Dick Flanagan, a master craftsman in a trade which has

almost been lost, will remain an abiding memory.

post a comment