Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Although the famous cathedral is rightly considered the physical and emotional centre of Canterbury in England, the historic old town holds other delights and diversions, especially if you are there with children who might not see the point of dead people made of stone and really big stained glass windows.

And, after a few hours of peering at strange inscriptions about people we never knew, who could blame them?

Which is where Rupert Bear, the slightly spooky Canterbury Tales museum (“Medieval Misadventures”) and the Roman Museum come in. And they are all within easy walking distance of each other in the middle of town.

Yes, they are museums, but with interactive stuff and things for kids to play with, they are more diverting for younger eyes than yet another plaque.

That said, all of them are equally interesting for adults – unless Rupert Bear meant nothing to you – and at the Roman Museum below street level you do wonder why, around 450AD, the Romans suddenly abandoned Durovernum Cantiacorum.

It was a city they had created and occupied for three centuries and where they had built beautiful bathhouses, a large D-shaped coliseum and markets. They seemed to have settled in rather comfortably.

Short answer: Wars elsewhere in the empire took them away, and so the city fell into disrepair before becoming an Anglo-Saxon settlement and life began again.

As with so many Roman ruins, some in Canterbury were not discovered until recent times. When the city was bombed in 1942 a Roman house with beautiful mosaics – now within the museum – was uncovered.

Artifacts and

mosaics, reconstructions of houses and market stalls, computer

activities and hands-on contact with Roman objects mean a family can

spend a fascinating hour or two in the company of some of the

earliest inhabitants of Canterbury at the Roman Museum.

Artifacts and

mosaics, reconstructions of houses and market stalls, computer

activities and hands-on contact with Roman objects mean a family can

spend a fascinating hour or two in the company of some of the

earliest inhabitants of Canterbury at the Roman Museum.

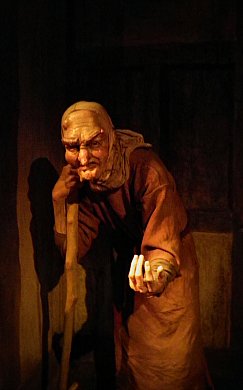

Those who know their literature and are a bit sniffy about it will find the Canterbury Tales attraction across High St more interesting than they might expect. Of course Geoffrey Chaucer's famous stories come in for some editing – although the essence of The Miller's Tale, buttocks out the window and all, remains – but there is fun to be had in the deliberate gloom where life-sized characters move, some looking alarmingly real.

The audio guide is essential as it tells edited versions of five stories (there's a children's version of the commentary) so even if The Canterbury Tales went past you, you are taken into this 14th century world of fables, trickery, bawdy doings and romance.

If it is more history you are after then the Museum of Canterbury on Stour St will certainly oblige, not the least with an amusing Bayeux Tapestry-style story of Becket's life drawn in cartoon form by Oliver Postgate in 1987.

There are plenty more artifacts here – ancient stone carvings of mythological beasts only unearthed in 1983 when workers were excavating Church Lane – but frankly I came to see the Rupert Bear exhibit.

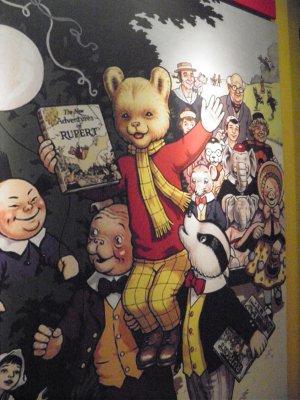

Originally drawn by Canterbury artist and book illustrator Mary Tourtel (who had the good fortune to marry an editor of the Daily Express), Rupert Bear is one of the most popular and enduring of all British cartoon characters. Tourtel's first single-frame illustration appeared at the bottom of a women's page (in the Daily Express, of course) and Rupert's career – and hers – took off.

Tourtel came from a gifted family – her father and a brother worked at the cathedral making and restoring stained glass and another brother was a book illustrator.

Rupert Bear is still a regular feature in the Daily Express and he has enjoyed annuals, a soft drink named after him (Rupert Whizz Fizz), models and toys, and the affection of Paul McCartney who wrote and produced the animated film Rupert and the Frog Song, Rupert appearing in his video for We All Stand Together which went into Britain's top five.

Yet through the decades Rupert had very few illustrators after Tourtel retired in 1935. Alfred Bestall took over and is credited as standardizing Rupert's image. In the annuals he also placed him in exotic locations and landscapes and made a real art form of the otherwise limited square-frame format. He illustrated Rupert for 30 years, and stayed on until the early 70s doing the annuals.

His successor John Harrold also drew Rupert and his pals for three decades until 2008. Stuart Trotter has been producing Rupert since then.

Rupert Bear hasn't

been without controversy (there were the inevitable accusations of

racism) and in 1973 Rupert's brown face was changed to white without

Bestall's approval on the cover of an annual, and it was the last

cover he ever did. Artists and fans took Rupert very seriously.

Rupert Bear hasn't

been without controversy (there were the inevitable accusations of

racism) and in 1973 Rupert's brown face was changed to white without

Bestall's approval on the cover of an annual, and it was the last

cover he ever did. Artists and fans took Rupert very seriously.

By current standards Rupert Bear is rather a dull figure – he doesn't stand a chance next to Angry Birds or Bratz dolls – and no one would defend the awful rhyming captions of earlier years (which simply don't scan). But the detail in the illustrations, his slightly priggish nature and timeless adventures are quite endearing.

But maybe that's just me. I saw a Rupert annual there I'd had as a kid and came over the big softie.

Strange that in Canterbury, an ancient city with a swirl of complex, murderous, religious and political history, not to mention exceptional architecture, I should be moved by a book I had forgotten for more decades than seems healthy to count.

But that too is history, of a very personal kind.

In Canterbury, the Rupert Bear display brought out the kid in me when I'd had enough of being an adult.

post a comment