Graham Reid | | 4 min read

As with most people, I neither want, nor expect, to be held up at Immigration. But on Niue – a charming, tiny tropical dot of elevated limestone in the Pacific about three hours from Auckland – I was stopped. For a chat.

Niue is different like that. In the Customs and Immigration hall musicians and dancers greet family, friends and guests, and at Immigration the big guy behind the counter engaged in a friendly conversation, gave me tips on places to go and people to see, and when I walked off and said, “See ya” he laughed.

“You probably will”.

The following day I did and we chatted again. Of course the odds were high we'd run into each other because on a good day Niue only has about 1500 permanent residents. You can drive around the island in a leisurely hour – which doesn't count time pulling over for photos of fine churches, colourful gardens and ocean views – and your body clock slows almost to a stop.

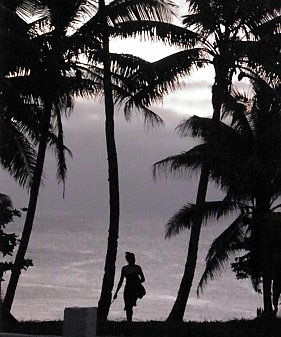

Niue – pronounced “noo-ee” by locals – rightly prides itself on an unforced friendliness, an ocean so clear you can often see up to 70 metres and a rugged coastline of bizarre rock formations and cathedral-sized caves which invite exploration and reward even the most amateur photographer.

The Auckland artist Mark Cross –

whose strikingly hyper-real paintings often reference the coastlines,

beaches and rocks of Niue – spends about half the year here in his

wife Ahi's village of Liku. He first went there in 1978 and was

struck by the clarity of the ocean and light, and the density of the

jungle which covers this small outpost.

The Auckland artist Mark Cross –

whose strikingly hyper-real paintings often reference the coastlines,

beaches and rocks of Niue – spends about half the year here in his

wife Ahi's village of Liku. He first went there in 1978 and was

struck by the clarity of the ocean and light, and the density of the

jungle which covers this small outpost.

That jungle – where the famous and frequently large uga (coconut crabs, pronounced “oon-ga”) live, feasting on fallen coconuts which gives them their distinctively sweet flavour – is thick and hazardous as the limestone floor is jagged and unforgiving. But paths through it lead down to white sand beaches, surreal caves which look like something Salvador Dali might have created and an ocean teaming with exotic fish.

Because the land drops away so sharply

you can stand on a low cliff, cast your line and catch deep sea fish

without getting your feet wet. So says Tony Aholima who takes me

searching for coconut crabs, to his various gardens carved out of the

jungle where he sometimes has to compete with wild pigs and chickens

for the crops, and down to coves from where you can see the Earth's

curve on the horizon. He also has his own outdoor office in the jungle, where nothing functions of course.

Because the land drops away so sharply

you can stand on a low cliff, cast your line and catch deep sea fish

without getting your feet wet. So says Tony Aholima who takes me

searching for coconut crabs, to his various gardens carved out of the

jungle where he sometimes has to compete with wild pigs and chickens

for the crops, and down to coves from where you can see the Earth's

curve on the horizon. He also has his own outdoor office in the jungle, where nothing functions of course.

A mecca for divers and fisherfolk, Niue boasts fishing charters and eco-tours, an excellent Matavai Resort (which has villa and motel options), Namukulu Cottages and Spa, a backpackers above the Yacht Club (no yacht or yachting experience required, you just sign in), and any number of cheap house rental options. The latter are available because so many Niueans have moved away to find work or education in New Zealand or Australia.

In every village – the punctation

points on the road around the island's perimeter – there are empty

houses, some abandoned and left to the elements, others kept in good

condition for guests.

In every village – the punctation

points on the road around the island's perimeter – there are empty

houses, some abandoned and left to the elements, others kept in good

condition for guests.

One day I went around for a few hours with Toamana Tours and Travel. My driver was the company's owner Hima Douglas who, among other things, had been the country's assistant finance minister, director of the local branch of the University of the South Pacific, was Niue's first high commissioner based in Wellington, got the Matavai Resort up and running . . .

His stories are fascinating: the nine-hole golf course was constructed by residents of “Her Majesty's Hotel” a.k.a. the prison; the bowling green was only made because Niue couldn't enter a bowls team in a Commonwealth Games unless they had a green; there were off-the-record political stories . . .

He also shows me where the massive sea surge came in during the 2004 cyclone taking out houses and buildings, explains the problems of customary land and absentee owners (you don't pull an empty house down because owners need it as evidence of their former occupancy of land), how the young Nukai Peniamina who brought Christianity to the island in 1846 was rejected by many people because of his association with Europeans who'd brought diseases . . .

“He also had an eye for the young ladies, but that's something you won't hear about in the books,” he said with a laugh.

For a small island Niue is rich with local history and stories, undeniably natural beauty, and exceptionally friendly people.

Niueans don't take themselves too seriously either. You'll delight in signs which read “New York style pizzas”, “The coolest ice cream and milkshakes in the world” , “Niue Yacht Club, the biggest little yacht club in the world” and at Sails Bar the one facing the cliff and ocean which announces “World's Toughest Gold Course, Par 1, 96.5 mtrs”.

You can eat seriously well here – fish and uga of course, and Avi's restaurant has genuine sushi chefs from Japan – and not many countries have a seaside cafe-cum-bar like Washaway Cafe which – if no one is around – works a help-yourself honesty system.

There's plenty to do (whale watching if it's the season) but if you aren't sure, just ask someone at Immigration on arrival, they'll tell you. Or you can do nothing.

By the way, the welcome sign at Immigration reads “Niue, undiscovered, unspoiled, unbelievable”.

And unlike most self-promotion, Niue proves to be all that. And more.

For more on Niue at Elsewhere, start here.

post a comment