Graham Reid | | 9 min read

The three hatchet-faced young men behind the desk at the upmarket hotel made it clear by their haughty indifference they didn't want us there.

And frankly -- impressive as their vast, luxurious, light-filled but conspicuously empty lobby was -- I didn't want to be there either.

But they were stuck with us. And we were stuck with them in a place which was allegedly Goa . . . although I'd seen scant evidence of that on this arduous day getting here to Goa-Perhaps . . .

At best this rich-folks retreat was Goa-Adjacent. Or Goa-May-Be-Somewhere-Nearby.

But it wasn't my idea of “Goa” with its bars, bikini babes, grooved-out soundtrack and whatever Goa I'd had in mind from its self-promotion.

Mutual irritation was heavy in the air-conditioned lobby as the mood became one of a sullen Mexican stand-off.

I'm in India and it wasn't supposed to be like this, I said to the French couple beside me. They nodded with typically Gallic shoulder-shrugs.

This escape from our real-world lives should've been wonderful but, for our grumbling group at the desk, disappointment hung like a dank cloud of resentment on this perfect blue-sky day.

Yet, for me, it had all begun so promisingly . . . and I couldn't know what would happen with unexpected ferociousness just a few hours later.

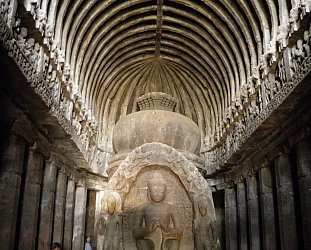

A fortnight previous a high-end travel magazine asked if I'd like a trip in India. It was short notice but my dance card was empty. The trip would be from Mumbai to Goa then up to the magnificent ancient caves and sculptures at Ajunta and Ellora. Back in Mumbai I could stay longer, the guy on the phone said, if I wanted to pony up for my own accommodation.

I checked the cost and availability of a room in a YMCA in Mumbai (an air-punched “Yes!”) and called back to confirm. To get even better news.

I would be on a luxury train with my own cabin. And butler, as it turned out.

However, I've never been enthusiastic about train travel. You see something fascinating but go straight past it at speed. And in this case, was a luxury train the way to connect with the dirty diversity and dramatic colors of what their tourism people sell as “Incredible India”?

But the opportunity was too good to refuse and so, one sticky-sweat 90-degree afternoon, I was standing on a platform in Mumbai -- the air blown by the acrid smell of burning plastic from fires across the tracks, the smoke of pervasive incense and the ammonia-whiff of piss -- as my handsome train pulled up.

This was a trip with an impressive itinerary. But that quickly became our captor because the train – with a gym carriage, two restaurant cars and an excellent, well-stocked bar – would have to spend long durations at stations, sometimes overnight.

So our journey required lay-overs at often small and remote railway sidings, because you can't haul a half-mile long train into a main station and take up a track and platform. And that would mean an air-con bus to a distant temple, fort or some-such; then back in the bus for the return journey to the train.

India was always outside windows and after two days there was growing discontent among passengers.

Goa – shops, people, nightlife, clubbing – was not something we were scheduled to see.

Off the train, on the bus, a walk through a typically dreary market selling nothing you wanted to buy (least of all wet but unrefrigerated fish), an old Portuguese district of a few picturesque streets . . .

The itinerary then required we return to the train for lunch, stay there that afternoon and later go to a hotel dinner-and-a-show.

On a pretty Portuguese-influenced street I made my dissatisfaction known to some like minds and back at the bus we announced we wouldn't be doing that.

Our hosts-cum-minders were alarmed. The guests were revolting . . . and worse, not following the schedule.

But we wanted to see Goa, wherever that might be, so we'd just get taxis there then meet the rest of them at the hotel later. Okay?

But, sirs . . . And madams . . .

There was a politely heated discussion, we were questioned – grilled actually – about how would we'd the hotel (“Because you'll give us the address for the taxi driver?”) and then . . .

Our minders disappeared.

So we waited.

And waited.

One minder returned to listen to our complaints again, then evaporated like smoke into the afternoon heat. He was replaced by another who did the same.

Eventually one of the more silver-tongued came back and said he sympathized. We should of course see the other part of Goa but, he said, it was quicker to get there if we took a taxi from the train.

And this – as British colonialists discovered – is power of India: the weight of it erodes you; the oppressive passive non-aggressiveness of it; the very Indian-ness of it en masse which saps your strength. It's Gandhi-as-travel agent prepared to stand there forever until you give up and go away.

It's the triumph of the unwilling.

And there's the heat, the sheer number of watching eyes, the always-there face which listens and wants to help but . . .

We were worn down, and after a 45 minute drive back to the train, our minders on the platform reassured us -- with that suffocating politeness Indian gentlemen can pile on -- taxis would be ordered. Meantime, we had time for the lunch which had been prepared.

We shrugged in despair. After half an hour at the table I said to my new best friend from Holland, “Have you noticed everyone else is getting served before us?”

So we, the revolting ones, waited.

By the time our lunch arrived it was mid-afternoon. The taxis hadn't shown.

But sir, this station is a very long way from the city, our silver-tongued guide informed us.

I'd lost the energy to argue and by the time two taxis arrived the Italian women had decided to stay on and use the gym.

Silver-tongue said the hotel was on a beautiful Goan beach.

Right, we revolting guests triumphantly resolved, we'll just go straight there and have a swim then meet up for dinner.

The taxis would be 40 rupee each, he announced.

I got in the front of one and two French travel agents got in the back. And away we went.

And went. And went even more.

We drove through empty fields and sparsely populated villages, through narrow town streets and beyond into fields again.

“You know where this hotel is?” I asked the driver whose English was as limited as my Hindi.

He drove on furiously. The French and I began laughing like drains.

“He does not know, non?”

Non, he does not.

After half an hour the furrowed-brow but effectively mute driver admitted defeat and asked a passing civilian.

The man pointed . . . and away we went.

And went. And went even more.

By the time we reached the hotel the sun was setting and the smell of our buffet hung low in the air.

And “40 rupee” for each meant “40 rupee for each in the taxi”.

We paid, we'd lost, but were here so, in a weird way, we had . . . won?

But -- we were firmly informed by the three hatchet-faced young men alarmed at our pre-emptive arrival – we could not use the changing rooms.

Two taxis of good-natured but beaten people laughed at the absurdity, changed in the smelly beach toilets, swam on the deserted beach then went to the bar. We had no idea if we were at Goa, Goa-Adjacent, or Goa-Probably-Somewhere-Else.

“Incredible India, huh?” I said to my Dutch friend.

At the buffet – excellent, the day almost redeemed by it – a group sang Portuguese-Indian versions of popular hits of the Seventies. Not local or even subcontinent hits, but those by Eric Clapton, Phil Collins and so on. By the time they got to Neil Diamond's classic “Sveeee caro lyin' . . . da-da DAAA” we realized there was only one way to make this long day interesting.

We drank even more, and salvaged some sense of victory over our hindering hosts.

And then the announcement. On the bus back to the train. Now. Quickly please.

But in our party of 20 or so we'd enjoyed different beverages: bottles of wine, beers and soft drinks. So, “Separate cheques, please”.

The travelers were having sweet revenge on hurry-up silver-tongue and his men. As we trickled onto the bus we were laughing loudly about the chaos and comparing notes with those who had remained with the train.

So you didn't see Any-Goa-At-All either?

“Incredible India,” I said to the people around me as we pulled away from the hotel courtyard, and we laughed.

It was short-lived.

In the blackness through rural roads, candle-lit villages and weakly illuminated towns, our bus driver passed perilously close to a man on a motorcycle – who just briefly I saw beneath me out the window – and clipped him.

There was a heart-thumping thud and the scour of metal on asphalt.

People felt it, our bus stopped, within minutes outside the windows there was the customary crowd-from-nowhere which India can provide and then – surprisingly – our driver got back on.

The motorcyclist was fine apparently, just shaken.

There was a sombre mood on the journey back.

Suddenly from out of the night with

relentless persistence, our bus was surrounded by angry men and boys

on motorbikes, scooters and bicycles. With fists shaking and voices

raised they slowed the bus and forced it to a halt.

Suddenly from out of the night with

relentless persistence, our bus was surrounded by angry men and boys

on motorbikes, scooters and bicycles. With fists shaking and voices

raised they slowed the bus and forced it to a halt.

They banged on the window and increasingly angry voices from the darkness demanded the driver get off. The mob thumped the sides of the bus, flaming torches punctuated the night. A stone cracked against the glass.

“Tell him to get off, they'll kill us,” shrieked an English woman beside me.

“Someone call the police,” she screamed. “They'll get on and kill us all!”

In the half-light I saw – just for a moment – the wild eyes of a young boy with a rake raised in inchoate fury. He looked like he'd murder me without a second thought.

A British video-blogger ran to the front with his camera, filming everything, just in case . . .

Some Indians from Europe shouted something out the window at the mob . . .

The police were coming, the Indian man told us, we just had to wait . . .

A European woman somewhere behind me started screaming, outside a rage of villagers gathered like a storm. There was fire in the night.

In the centre of fury, we waited.

And we waited.

Over time -- maybe 10 minutes, it seemed longer -- the howl of the mob abated as they wearied and realized the driver wasn't getting off. When the police arrived the crowd dissipated into the darkness and our driver took us back the train.

A few of us went to the bar and drank silently for a while, then the Honeybee brandy took hold and we found humour in the day: the fly-filled fish market, the lost taxi driver, the haughty desk clerks.

The fearful English woman scuttled past, embarrassed by her outbursts.

Soon enough we all went back to our cabins where an underpaid man in an over-dressed Raj-uniform waiting patiently, just to open the door for us.

The following morning the train pulled out, heading for Wherever-Adjacent.

And away we went.

And went even more into that astonishing, beautiful, bizarre, bewildering, rewarding and always surprising country.

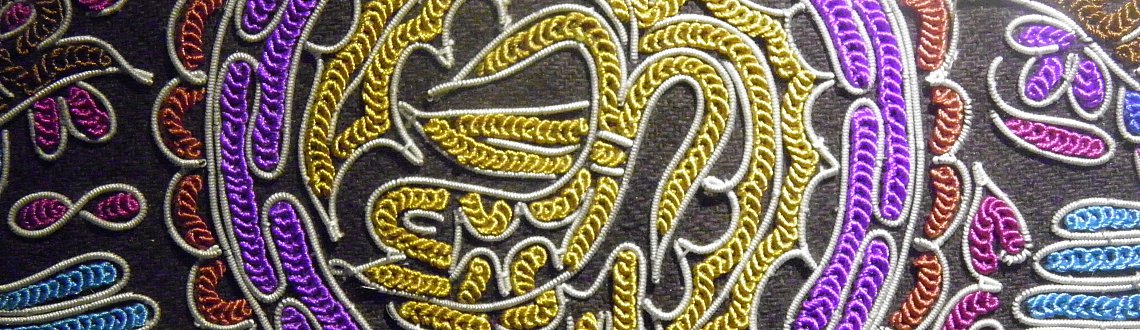

A place where ancient spirituality and modern society fight for space in the 21st century, and where an ease of meditative moments can be counteracted by excessive emotion.

Along the way the Dutch guy and I discussed the previous day, I said it had been like a raga, the classical Indian musical form: It started slow, we improvised a bit and then it ended in a fiery and fast coda.

He looked at me blankly so -- with as much irony as cheap wit – I quoted the country's tourism slogan again.

“Incredible India.”

We didn't laugh.

Aroha Mahoney - May 8, 2016

Oh, how this brings it all back. We had an extended trip through parts of India in the early 90s, the time of the riots about the Golden Temple in Amritsar. We went to get on an overnight train in Jaipur to go to Agra, in the innocent belief that we had a sleeper booked. We had a piece of paper saying so. But what our piece of paper actually meant was that we merely had the right to make a booking at the station, always supposing there would be something available. Consternation ensued, but eventually we were given a berth (in a manner of speaking) on the train. But worse was to come. At the crack of dawn we were decanted at Tundla Junction at the border between Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, 25k fr0m Agra, because the gauge of the railway changed which meant changing trains. But no trains were running because overnight a state of emergency had been declared. We were the only Europeans on a platform crowded with locals. Eventually we got a taxi, but when we got to the outskirts of Agra we were turned back by the army – no-one was allowed in

SaveBack to the junction, at which point my husband decided he wasn't going to pay because the taxi driver must have known what was happening. The mob got angry and it began to get very nasty, at which point a railway official collared us and locked us into a small branch line train. Then another man got in and the train lurched off. At one point it stopped, went backwards, then there it sat for about 2 hours. Finally it chugged off again, arrived at a suburban station and a ticket man came along and told us to get off. But as I attempted to do so a soldier appeared and barred my way with a lathi – no-one was to be allowed off. To cut a long story short we were eventually taken into the main station, where the platform resembled a scene from hell. There was a curfew, no transport and buckets of excrement everywhere. We finally ended up at a small local hotel where we holed up for 3 days until the state of emergency was lifted. But the real bonus was that the curfew was lifted every day for a couple of hours to let locals go shopping. We found a rickshaw driver (inevitably, cousin of the proprietor) who took as to the Taj Mahal and waited for us. There was virtually no-one else there. Just fabulous.

post a comment