Graham Reid | | 5 min read

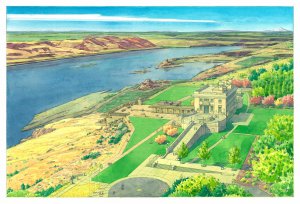

Sam Hill had a vision fairly common among the wealthy: an agrarian utopia where happy workers would toil in fertile fields, their cheery lives overseen by their benign master -- himself, of course -- from a bastion high on a hill above.

Unfortunately Sam -- a railway man and an incurable builder of roads -- picked the wrong hill in the wrong place. It is near The Dalles in north central Oregon, a crossroad city we ended up in on our way to Seattle.

The Dalles was given its unusual name by French-Canadian trappers. It means gutter stones and the place is so called because the trappers saw the towering rocky bluffs channelling the nearby Columbia River in much the same manner. The riverside settlement was the end of the Oregon Trail and from here fortune seekers would take the Columbia 300 winding kilometres to the Pacific coast, or make for the productive Willamette Valley overland about 150 kilometres southwest.

All fascinating historical stuff to be sure, and bold murals on brick buildings in the old part of the town depict famous moments in the life of The Dalles. But there seemed no pressing reason to linger here until over breakfast Chuck, owner of the Windrider Inn where we have spent the night, mentions Sam Hill.

“Man, you gotta go see his place,“ he laughs. “It’s enormous. And while you’re up there check out his Stonehenge down the road.”

This sounds too crazy to ignore so after coffee and handshakes we drive back east along the Columbia and cross into Washington state where Hill purchased 6000 acres of land in 1907.

His vision was of a Quaker farming

community working riverside land where the moderate climate ensured

that fruit ripened and crops grown here would mature a few weeks

before those in other parts of the state.

His vision was of a Quaker farming

community working riverside land where the moderate climate ensured

that fruit ripened and crops grown here would mature a few weeks

before those in other parts of the state.

It was, at least in his imaginings, the ideal place for his own personal utopia. The view wasn’t bad either.

So Hill ordered the building of a palatial home -- Maryhill, named for his daughter -- on the windblown bluff above with a view of the farmland and mighty Columbia below, and what appears to be half of Oregon on the opposite side.

“I expect this house to be here for a thousand years after I am gone,” Hill grandly announced when construction on the three-storey building began in 1914. Unfortunately not many others wanted to live in this remote place.

You can imagine their question: “The Dalles? And where would that be?”

Within a few years it was obvious Hill’s utopia would never be realised. Work at Maryhill ceased.

But that’s where the story of Maryhill really begins.

Hill travelled widely and in Europe had made friends with the avant-garde dancer and choreographer Marie Louise Fuller. When she heard of the building standing incomplete she suggested Hill finish it and turn the place into an art museum.

The idea appealed to Hill. After all, what else was he going to do with it?

In 1926 Maryhill was dedicated by his friend, Queen Marie of Romania who donated her wedding dress and heavy, somewhat ugly, wooden furniture from her castles out of gratitude for the assistance Hill had given in the reconstruction of her country after World War I.

But that’s not all that is in this

breeze-battered but absorbing museum.

But that’s not all that is in this

breeze-battered but absorbing museum.

A middle-aged docent points us towards the utterly unexpected here in the most empty part of Washington: a large permanent exhibition of Rodin sculpture, drawings and plaster models; and the section devoted to the remarkable life of Fuller.

Born near Chicago in 1862 Fuller had, by her late twenties, appeared in theatrical productions and Buffalo Bill’s travelling show, and performed at London’s Gaiety Theatre where she observed dancers using flowing skirts to create a sense of free-flowing movement.

She learned the visual power of coloured lighting on gossamer silk and long swathes of the material, and adapted the Gaiety style to create what she called her Serpentine Dance. She performed this to audiences in America but felt she wasn’t being fully appreciated for the innovator she undoubtedly was. In 1892 however she performed it at the Folies Bergere in Paris, was an overnight sensation, and became a symbol of the Belle Epoque era. She was, according to later writers, the embodiment of the Art Nouveau movement and her company presented Isadora Duncan to enthusiastic Parisians.

Fuller’s most famous piece was a dance to Debussy’s La Mer in which waves of shimmering silk were moved by dancers beneath her costume.

Fuller, known as La Loie and who enjoyed a number of lesbian relationships, enhanced her performances with lantern slides, coloured gels and florescent paint, and had a laboratory built in her studio where she could experiment with colour. She consulted Thomas Edison on the use of light, and the Curies about their work in electricity and with radium.

The writer Stephane Mallarme hailed her performances as “an artistic intoxication and an industrial achievement”.

At Maryhill there is jerky footage of one of her many imitators and even that, capturing the sensuous flow of layered silk and other diaphanous fabrics, is thrilling.

Her friend Auguste Rodin -- whose work she collected -- considered her “a woman of genius”. Anatole France -- the French writer and critic who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1921 -- wrote the introduction to her autobiography, and she counted among her devoted following Jean Cocteau.

Fuller died in Paris in 1928 and is buried in Pere Lachaise: “A magician is dead, a butterfly has folded its wings” said one French newspaper.

But Maryhill, to which she donated her Rodin collection, is as much her legacy as it is that of moneyman and patron Hill.

Downstairs in a huge airy gallery are the Rodin drawings and sculpture (including models and studies for his greatest works like Balzac and The Burghers of Calais), and period photographs and posters of Fuller.

But within Hill’s eclectic collection there is also a section devoted to Native American cultures along the Columbia, and a changing display of exotic chess sets which include some from Cambodia, Indonesia (the pieces as characters from the Ramayana), India (in Mogul style with a male counsellor rather than a queen) and China.

“Not many people outside the state know about us,” says our prim docent as we are admiring the chess pieces. “I think that’s quite a pity, don’t you?”

We nod in mute agreement. You don’t see a queen’s wedding dress the size of a small car every day, least of all in the Pacific Northwest.

Down one of Hill’s roads is his

full-scale concrete replica of Stonehenge, built as tribute to

soldiers of the county who lost their lives in World War I.

Down one of Hill’s roads is his

full-scale concrete replica of Stonehenge, built as tribute to

soldiers of the county who lost their lives in World War I.

But it is not a war memorial. Hill was told, incorrectly, that the original Stonehenge had been a place of sacrifice. His replica was built to remind people that humanity was still being sacrificed to the god of war.

Standing here, the wind whipping straight down from Canada, it is hard to imagine what drew Sam Hill -- who died in 1931 and is buried on the hill below -- to this lofty and lonely bluff.

But he was an uncommon man: a Quaker pacifist during the turbulent war years; a man who made his money in heavy industry but harboured the dream of a farming community; and a patron of the quiet arts who took great joy and excitement from noisy railways and roads.

We walk back to Sam’s monumental museum, nod hello to the only other two people here on this day, and sign the visitors’ book.

The docent glides up and looks at what we have written.

“New Zealand? And where would that be?”

post a comment