Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Improvisation for Oud 1 (live 1969)

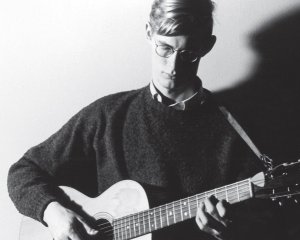

Just a thought, but if Sandy Bull had been British, magazines like Uncut and Mojo would be running major, rediscovery features about him and placing him in the pantheon of innovative guitarists like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Richard Thompson and – especially – Davy Graham.

But Bull – who recorded fewer than a dozen albums between his debut in '63 and death in 2001 – barely gets any recognition, despite having been an innovator on acoustic, electric and pedal steel guitars, oud, banjo, bass, sarod and with the available technology of his time.

Yet there are only a few of his albums on iTunes and Spotify, although his records – secondhand of course – are cheap on e-Bay. Largely perhaps because few have heard of him.

Yet Bull – born in New York in '41 as

Alexander Bull – was effecting effortless fusions of folk, jazz,

classical and world music at a time when others were hailing the

folk-pop of Donovan and the most naïve efforts of the Incredible

String Band (who to their credit really did become something quite

special soon enough).

Yet Bull – born in New York in '41 as

Alexander Bull – was effecting effortless fusions of folk, jazz,

classical and world music at a time when others were hailing the

folk-pop of Donovan and the most naïve efforts of the Incredible

String Band (who to their credit really did become something quite

special soon enough).

But in addition to all that Bull overdubbed himself in the studio and when he performed live deployed a primitive drum machine and backing tapes of himself to play off.

Drug addiction took him out of the game for a few years at the dawn of the Seventies, just when he should have been enjoying his greatest acclaim.

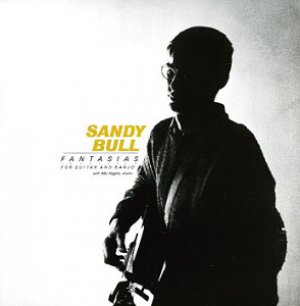

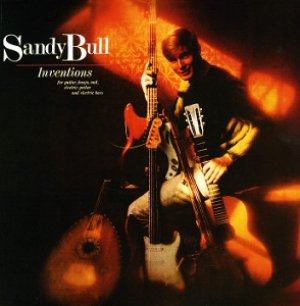

But before then he'd created a small but impressive body of work, especially on his first two albums – Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo ('63) and Inventions ('65) – which still take some reckoning with today.

Even his third album E Pluribus Unum ('69), which some critics deride a little, holds special pleasures.

These three albums were recorded for the daring Vanguard label whose catchphrase for a while was “Recordings for the connoisseur” and which released folk, blues, Country Joe and the Fish, Buffy Sainte-Marie and John Fahey.

Bull was in the advance guard of folkadelic music, and in that regard is probably an easier proposition for contemporary listeners than he was for those at the time.

The young Bull came from musical but divorced parents: his dad lived in Florida where the boy would hear country music and African drumming, his mother was harp player who called her stage act From Bach to Boogie-Woogie.

He was impressed by Pete Seeger's folk so picked up banjo (at eight he had lessons from Erik Darling of the Weavers) and then guitar, studied composition at Boston's University College of Music, joined the folk scene in Cambridge, Massachusetts and played in California.

He picked up an interest in Arabic and Indian

music (this well before the sitar came into raga-rock) and, according

to Nat Hentoff who wrote the liner essay for Inventions, in '64

played the Newport Folk Festival (although he doesn't seem to appear

on any of the official billings).

He picked up an interest in Arabic and Indian

music (this well before the sitar came into raga-rock) and, according

to Nat Hentoff who wrote the liner essay for Inventions, in '64

played the Newport Folk Festival (although he doesn't seem to appear

on any of the official billings).

The previous year he'd recorded his debut for Vanguard and was accompanied by jazz drummer Billy Higgins, perhaps best known for being in Ornette Coleman's early group.

The first side with Bull on acoustic guitar was a 22-minute melange of musical styles entitled Blend which opened in Arabic then Spanish mode.

The second side started with his treatments of Carl Orff's famous Carmina Burana and a piece by English renaissance composer William Byrd, then a folk original Little Maggie on banjo and another original, the 10 minute Gospel Tune, on shimmering electric guitar.

It's worth remembering that at the time

of its release the Beatles were singing I Want to Hold Your Hand, Bob

Dylan was just making his name with original songs and neither Arabic

or Indian music had entered the lexicon of folk or rock.

It's worth remembering that at the time

of its release the Beatles were singing I Want to Hold Your Hand, Bob

Dylan was just making his name with original songs and neither Arabic

or Indian music had entered the lexicon of folk or rock.

For his follow-up Inventions he added oud to his armory and, again with Higgins, opened the album with the 24 minute Blend II which – as Hentoff notes – includes references and allusions to Turkish and Arabic music (Bull had met oud player Hamza El Din in Rome a few years previous), Coleman's Lonely Woman, the country song Wabash Cannonball, tunes from Pakistan and Afghanistan, American folk and ends with a dialogue between drummer and guitarist in the manner of the closing passages of a raga.

Elsewhere he plays Bach and offers a 10 minute solo exploration of Chuck Berry's Memphis, Tennessee on electric guitar.

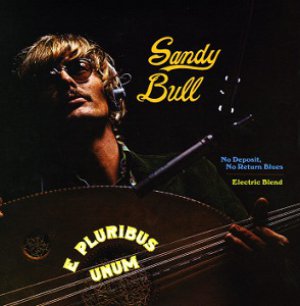

E Pluribus Unum found Bull in

multi-tracked solo mode on two side-long pieces; No Deposit, No

Return Blues and Electric Blend. It certainly lacks the focus of his

earlier work (Higgins perhaps offering that grounding when things

threatened to fly off into aimless self-indulgence) but there is no

denying it was out there.

E Pluribus Unum found Bull in

multi-tracked solo mode on two side-long pieces; No Deposit, No

Return Blues and Electric Blend. It certainly lacks the focus of his

earlier work (Higgins perhaps offering that grounding when things

threatened to fly off into aimless self-indulgence) but there is no

denying it was out there.

As he increasingly was.

At the time Patti Smith was a fan of Bull's distracted fourth album Demolition Derby in '72 (“a real cool record” she wrote in her review in the New York Metropolitan Journal) but that would be it from Sandy for a while.

He kicked his habit a couple of years later and joined Dylan's Rolling Thunder troupe in '75 but it wasn't until the Eighties that he would record again. He'd adopted an itinerant lifestyle in the US, Europe and the Middle East.

“I tried to go places where other people weren't going,” he said in the liner notes to Re-Inventions, a '99 remasters compilation album, “just because I wanted to build something of my own . . . I kept trying to do different sounding records, and I'm sure I left a lot of fans behind as a result.”

His '88 album Jukebox School of Music found him also playing sarod which he'd learned from the master Ali Akbar Khan.

In the late Nineties he settled in

Nashville where he had a studio and started his own label Timeless

Recording Society. He played sarod on Kevin Welch's album Beneath My

Wheels, and oud on Sam Phillips' Cruel Inventions.

In the late Nineties he settled in

Nashville where he had a studio and started his own label Timeless

Recording Society. He played sarod on Kevin Welch's album Beneath My

Wheels, and oud on Sam Phillips' Cruel Inventions.

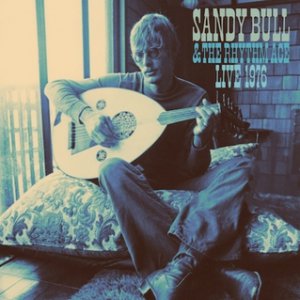

There would be other albums before his death, and two posthumous live albums: Still Valentine's Day 1969 released in '06 and Sandy Bull and the Rhythm Ace Live 1976 – him with his drum machine and backing tapes – which came out in '12.

But while many of his later albums confirm his particular gift for adopting and adapting music from many different sources, it is still those first three upon which his reputation as an innovator and boundary rider rest.

At the time of Inventions he explained his eclectic nature to Nat Hentoff like this: "There is so much [music] around today to pick from. It's one thing if you come from a solid background of one kind of music. But if you are like I am -- a city boy who got into music late -- it can be a natural course to build up something of your own from the music or sounds in music you most enjoy . . .

"Eventually all music is going to come together . . . As for me, I'm going to keep on seeing where this leads me. I'm going to keep on listening for what is going to come out of all kinds of music that reach me."

And he was as good as his word, he just kept listening.

He was a world musician and world citizen in the truest senses of those descriptions.

And that's why we need to talk about Sandy Bull.

.

Sandy Bull albums are on Spotify, see here.

.

For other articles in the series of strange or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

This article came about because two Sandy Bull albums (his second and third) were in a box of wonderful old vinyl sent to me by an Elsewhere subscriber. I knew the first Bull album and vaguely recalled hearing the second, but this gift sent me in search of Sandy. Thank you Joeke, I am working my way through the pile and more will appear from your generosity here or at From the Vaults in the near future.

Maurice - Jun 23, 2015

Someone in REM was a fan. They included his Carmina Burana Fantasy on a compilation for Uncut back in 2003 - I assume Peter Buck. That was my introduction to Sandy. Thanks for giving more info on him.

Savepost a comment