Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Dream Lover

The spirit and essence of rock'n'roll is impossible to define.

For some it was encapsulated by Little Richards' visceral scream and shout of “Awoobopaloobop Alopbamboom”.

For others it might be more like, “Make a fucking racket, show us your tits and blow up a car”.

If you are of the latter persuasion then New York's Plasmatics – fronted by Wendy O. Williams – in the late Seventies were only too happy to oblige.

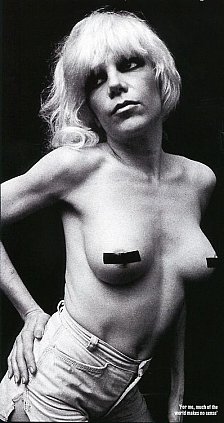

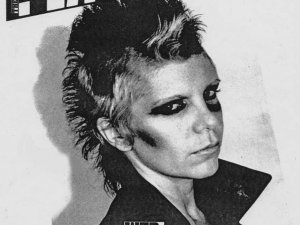

For some, Williams – a former stripper and adult porn actress who wore black pasties on her nipples – was the godmother of American shock-punk carrying a chainsaw and fronting a band which had a guitarist with a pink mohawk (Richie Stotts).

She was also the woman who – at 48 – went into her backyard in April '98 and killed herself with a pistol shot to the head.

She left a note which confirmed she'd thought about doing this for years – indeed she'd tried to commit suicide a couple of times previously – and that it was the act of a calm, rational person.

And, despite those two pivotal points

in her life, there was a lot more to WOW than just breasts and big

bangs.

And, despite those two pivotal points

in her life, there was a lot more to WOW than just breasts and big

bangs.

Wendy Orlean Williams was a complicated person who – with the Plasmatics – made music which was reductively simple. They were a construct of their manager Ron Swenson (who became Williams' partner until her death) and took their lead from the Ramones.

Their count-in was “ichi ni san shi”, one-two-three-four in Japanese.

They played CBGBs and musically erred to the metal end of nascent US punk with Williams wearing eye-catching attire (or not much at all).

Their live shows as they got bigger became more comedically violent as they blew up television sets and cars.

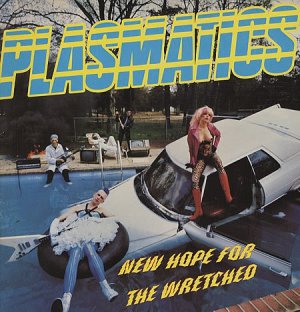

Their debut album was New Hope for the

Wretched in '80 on Britain's Stiff Records (the label which had as it

a slogan, “If it ain't Stiff it ain't work a fuck”). It was

produced by Jimmy Miller although to be fair, even he couldn't

salvage much from it: it is thrash punk of no fixed ability although

songs like the furious Living Dead and Test Tube babies do stand out.

Their debut album was New Hope for the

Wretched in '80 on Britain's Stiff Records (the label which had as it

a slogan, “If it ain't Stiff it ain't work a fuck”). It was

produced by Jimmy Miller although to be fair, even he couldn't

salvage much from it: it is thrash punk of no fixed ability although

songs like the furious Living Dead and Test Tube babies do stand out.

But Miller was descending into addiction.

However during the instrumental part of their assault on Bobby Darin's Fifties pop hit Dream Lover on the second side the musicians were isolated from each so couldn't hear what the others were playing.

It's like Pere Ubu gatecrashed a GBH gig.

It might just be their finest moment.

Coupled with their literally explosive shows and manager Swenson's art school background – he graduated in the conceptual end of things – the Plasmatics could have developed their auto-destruction into something akin to the Who-meets-Yoko Ubu.

It was the thrilling violence of their act coupled with Williams' pneumatic breasts and angry, sexual salaciousness (“When you're down on your knees I can feel it”) which was their appeal. The music almost became incidental to an act where she took a chainsaw to a guitar and shit got blown up.

There was a case to be made that in the

destruction of cars and television sets there was a powerful

anti-consumer statement being made . . . although you suspect the

teenage boys didn't quite go to a show for that.

There was a case to be made that in the

destruction of cars and television sets there was a powerful

anti-consumer statement being made . . . although you suspect the

teenage boys didn't quite go to a show for that.

And the Plasmatics pulled big audiences for their performance art-punk (which came with arrests for obscenity).

By the time of their final album Coup D'Etat in '83 they were – with a couple of new members – on the cusp of punk-metal and anticipating a whole new, emerging style.

Later there would be a short-lived tribute band: New Hope for the Plasmatics, of course.

Williams' solo career was highly

creditable – awards, critical acclaim – and she found fans in

Kiss, Alice Cooper, Motorhead (she and Lemmy did a duet on Stand By

Your Man) but her music career became less focused. She was in a

theatre production of The Rocky Horror Show, there was a brief

Plasmatics reunion, movie parts (Reform School Girls) and so on.

Williams' solo career was highly

creditable – awards, critical acclaim – and she found fans in

Kiss, Alice Cooper, Motorhead (she and Lemmy did a duet on Stand By

Your Man) but her music career became less focused. She was in a

theatre production of The Rocky Horror Show, there was a brief

Plasmatics reunion, movie parts (Reform School Girls) and so on.

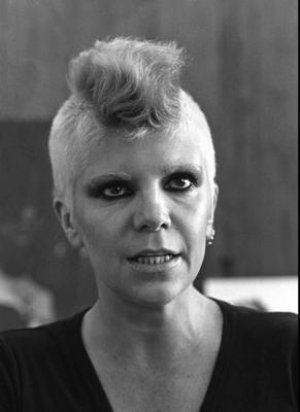

She all but retired in the early Nineties, but Williams was always smarter and more informed than her early stage persona let on.

She became a powerful and articulate advocate for animal rights and vegetarianism, and – years ahead of the game -- was outspoken about the amount of sugar in American food.

By the early Eighties she had quit smoking (no smokers in the dressing room, but alfalfa sprouts, tofu and honey) and was scrupulously clean to the point of not taking even an aspirin.

"I don't take anything that can dull my senses," she told People magazine – which once put her on their Best Dressed List – in '83. "Feeling good is the most important thing to me."

She jogged, swam regularly and used

weights.

She jogged, swam regularly and used

weights.

In fact, you could almost argue that despite the outrageous appearance – and Americans understand the notion of An Act – that Wendy O. Williams was a pretty damn good role model.

Hell, one less television set or automobile in the world is probably a good thing.

But when she retired she couldn't find a place for herself: She didn't want to become an aunt figure for young punks, didn't go to New York, worked with animals but couldn't see a future for herself and, by some accounts, started to hate her body.

Among the notes she left before her final act was one which read, “I believe strongly that the right to take one's own life is one of the most fundamental rights that anyone in a free society can have”.

Another read, “I die with a clean warm feeling like the sun and water we shared together as when birds fly or fish swim”.

Before she shot herself she put a bag over her head so whoever found her wouldn't have to see the full horror.

Ironically, many people in Storrs, Connecticut where she lived and sometimes served customers at a health food shop, had no idea who she was.

“If you weren't punk fans, you didn't know,'” said Cheryl LeBeau who interviewed Williams for her college radio show.

“All they knew was that she was a nice woman who knew a lot of vegetarian recipes.”

For other articles in the series of strange or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment