Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Needle of Death

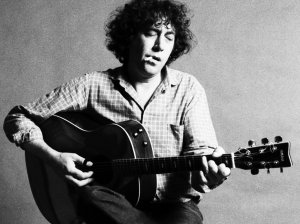

Few musicians have recoiled from the glare of fame as assiduously as British guitarist and singer Bert Jansch.

This solo artist and founder member of the seminal UK folk group Pentangle – less a band perhaps than a grouping of unlike minds and revolving membership -- was often an indifferent solo performer despite his obvious genius, was frequently drunk on stage (and admitted to sometimes nodding off while other members of Pentangle took solo spots) and would most often have rather have been down at the pub.

In an interview with Melody Maker in the mid Seventies he said, “[Fame] is not necessarily what you are looking for in life, to convince the whole world that you're a genius. Maybe all you're trying to do is earn a living.

“If I go to a pub I don't want everyone to know I'm Bert Jansch. I want to have a quiet game of darts.”

And the writer noted that Jansch's life

at that point “had devolved into a pleasurable routine of Putney

alehouses.”

The fact was that Jansch was an alcoholic, and

something of a reclusive and depressive man by nature.

“Unless you're really an excessive, falling-down drunk it's hard for people to notice,” said his partner in the late Seventies Charlotte Crofton-Sleigh. “Bert's drinking was much more a case of get up in the morning, go to the pub, go home and then back to the pub until it closes.

“He wasn't one for sitting at home

all day drinking. It wasn't mad, bingeing drinking as it had been

with Pentangle: it was a lifestyle so people weren't having

conversations with him about it.

“He wasn't one for sitting at home

all day drinking. It wasn't mad, bingeing drinking as it had been

with Pentangle: it was a lifestyle so people weren't having

conversations with him about it.

“Also, he had this amazing thing he could do of keeping people away from him.

“He could be in a crowded room and still sitting on his own, not because he was being nasty to people but because he exuded this thing of 'this is my space'.

“But when it came to the crunch, giving up alcohol was a decision he had to make himself”.

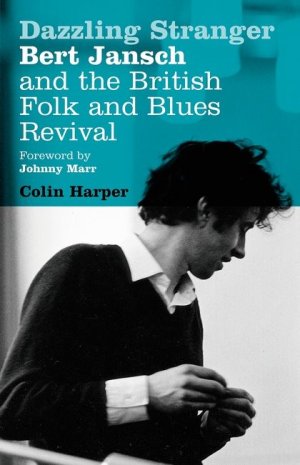

In his assiduously researched, exhaustive and sometimes exhausting biography of Jansch -- Dazzling Stranger; Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival – author Colin Harper writes a compelling portrait of this reluctant, flawed man who sometimes would have preferred being a gardener . . . but had been handed a gift.

Late in life Jansch said, “Now I've no other means of actually earning a living at all other than picking up a guitar. But what I'm happy with is that whatever I create, a lot of people want to hear it . . . If I'm at home I'm playing the guitar, it's a continual process . . .

“I don't like to stand on a pedestal or a stage saying, 'I'm the greatest player in the world'. That's nonsense.

“To me life doesn't work like that. The record industry works like that.”

And – as he bounced between a

revolving door of managers and record companies – he knew how the

music business worked. And he didn't like it.

And – as he bounced between a

revolving door of managers and record companies – he knew how the

music business worked. And he didn't like it.

Many consider Jansch one of the greatest of all acoustic guitarists, and his many albums (a few brilliant, some much less so) have constantly been reissued. There is another reissue being undertaken at present, many of the albums coming out again on vinyl for a new generation of post-folk and alt.folk fans.

And Jansch – who for many decades remained a marginal if not obscure figure – always had, and still has, fans.

Neil Young, who invited Jansch to open for him on a tour was a lifelong fan and saw him as the equal of Jimi Hendrix, whom Jansch had appeared with on three bills in the late Sixties, and admired very much.

“As much of a great guitar player as

Jimi was,” said Young, “Bert Jansch is the same thing for

acoustic guitar.”

Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page – who borrowed

more than a few licks from Jansch in his acoustic work – said, “He

tied up the acoustic guitar in the same way that Hendrix did the

electric.”

Fans today include former-Smith Johnny Marr, Bernard Butler (Suede), Colm O'Ciosoig (My Bloody Valentine) and Hope Sandoval and David Roback (Mazzy Star) who all appeared at Jansch's 60th birthday celebrations alongside folk legend Ralph McTell.

In the folk world, right from the time he arrived in London in the Sixties, people spoke in awe of his talent . . . and also of his capacity for booze, his discomfort on stage, his capacity to be a solitary in a crowded room and how he could, without trying, simply shut people out.

Musician Andy Irvine said of him, “There was a certain awesome, semi-legendary quality about him, even as he sat there and played. . . You could say, 'Hi, Bert' . . . 'Yeah', but you wouldn't go any further . . . You could go into a place and he would be there . . . but Bert was a little distant. Because he was silent and [other musicians] were loud there was a kind of awe.”

Donovan -- who had seen Jansch play, was influenced by his finger-picking and became a friend -- covered a couple of Jansch songs early in his career (Deed I Do and Do You Hear Me Now). They also shared the affections of Beverley Kutner (who later married John Martyn) and Donovan -- who refers to her as Beverley Chamberlain in his autobiography -- wrote The House of Jansch about that love triangle.

For many years in the Sixties Jansch seemed an itinerant, just sleeping at whosoever's house he ended up in. Throughout his life there were a series of women, some of whom became wives, others just last a few months. Jansch seemed as emotionally detached from them as he did sometimes from his career.

He founded Pentangle with follow player John Renbourn and although they were a very long-running, off-again project, Jansch was most often unhappy in the band. When they toured the drinking became heroic and constant.

Biographer Harper – who is generous towards a man whom he knew well but is never blind to his manifest faults – puts Jansch into the context of the British folk scene in the Sixties and beyond, and clearly he was a bad fit.

Page after page in the biography make reference to Jansch's drinking (later people simply speak of “boozing”) and his unwillingness to rehearse, perform professionally or engage much with fellow travellers or audiences.

Yet every now and again on record

Jansch would connect completely with his elusive muse as on albums

like Avocet, LA Turnaround – recorded in Los Angeles with, among

others, guitarists Mike Nesmith, Jesse Ed Davis and fiddle player

Byron Berline – as well as the compelling Heartbreak and When the Circus Comes to Town.

Yet every now and again on record

Jansch would connect completely with his elusive muse as on albums

like Avocet, LA Turnaround – recorded in Los Angeles with, among

others, guitarists Mike Nesmith, Jesse Ed Davis and fiddle player

Byron Berline – as well as the compelling Heartbreak and When the Circus Comes to Town.

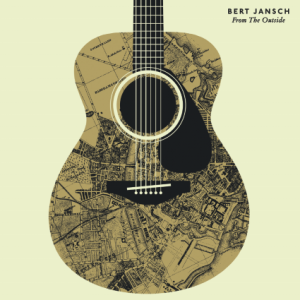

It is upon albums like these – and obscurities like From the Outside (originally only 500 copies released in Belgium) and a few Pentangle albums – which Jansch's legend rests.

However it speaks volumes about Jansch that different writers single out other albums: The Mojo Collection; The Ultimate Music Companion published in 2000 and edited by Jim Irvin identifies Jansch's self-titled debut from '65 (on which he used a borrowed guitar) calling it Britain's first singer-songwriter album and Rosemary Lane ('71) as well as Pentangle's Sweet Child ('68, “their definitive work”).

The volume also directed listeners to Jansch's When the Circus Comes to Town: “Everything that was great and magical about Jansch's work in the Sixties is here, present and correct,” wrote Harper in Mojo at the time, “updated with sparse but thoroughly modern touches”.

In Electric Eden; Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music, the writer Rob Young adds Jansch's second album It Don't Bother Me (also '65) and Jack Orion (with John Renbourn and Annie Briggs): “[It] staked out the cardinal points of the Pentangle sound”.

In the current reissue Uncut recently called Rosemary Lane “a masterpiece”.

The most recent reissue is his spare

solo album From the Outside ('85) which pulled together songs from

various sessions in Denmark and London. It was bleak time and the

songs reflect that: Get Out of My Life addresses his alcoholism, the

ever-present nuclear threat, the rumination of Time is An Old Friend

and the metaphor of a river running to the ocean which might be

Jansch's image of himself.

The most recent reissue is his spare

solo album From the Outside ('85) which pulled together songs from

various sessions in Denmark and London. It was bleak time and the

songs reflect that: Get Out of My Life addresses his alcoholism, the

ever-present nuclear threat, the rumination of Time is An Old Friend

and the metaphor of a river running to the ocean which might be

Jansch's image of himself.

Harper is a fine music critic in his book and dismisses the disappointing solo and Pentangle albums but draws you towards Jansch's most influential work.

And it is often quite remarkable.

Jansch's early influences were black American singers and players like Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee and others he saw in concert. He listened intently to Davy Graham (who was exploring different tunings) and adopted and adapted his famous Angi (by including Cannonball Adderley's Worksong in the central passages). He listened to jazz (Charles Mingus a particular favourite) as much as old British folk in the Sixties. When he sang his voice was gritty (many didn't like it) but authentic.

“People saw him as a rival to Bob Dylan,” said Martin Carthy. “When his first album came out it really was a big day.”

Songs from the album – which included his seminal Needle of Death and Angi (sometimes Angie) – were covered by Marianne Faithfull, Julie Felix and Donovan.

But Jansch would have little truck with fame, self-promotion and all the rest of it. He went his own way, sometimes tottering.

In '87 Bert Jansch fell seriously ill – “The drinking had got so bad I couldn't lift a glass,” he said of himself at the time – and was rushed to hospital. A lifetime of booze had caught up with him. He was described as being “as seriously ill as you can be without dying”. His pancreas had crashed.

And, in another story, that would have been the end of Bert Jansch.

But he survived and quit drinking immediately. After a few years he came back, a few years further on he stopped smoking, and his career started to pick up as there was a folk revival in the post-punk era.

His late career stabilised, he began to accept and even enjoy some of the acclaim he was being accorded by peers and new generation of guitarists. He worked regularly, recorded efficiently, reconnected with Pentangle (not as satisfactory as it should have been however) and even mooted the idea of a series of television films of the great, surviving folk artists of his era.

That series Acoustic Routes brought out Martin Carthy, one of Jansch's original inspirations Brownie McGhee, Al Stewart, Wizz Jones, Davy Graham, Ralph McTell and others.

He toured frequently – Germany, the US, the UK, Denmark where he'd always been popular and Spain (“that season's winner in the 'who's next for a folk revival?' stakes,” says Harper).

Bert Jansch lived almost 25 years beyond what might have been his deathbed farewell in '87.

In '72 on the Pentangle album Solomon's Seal was Jansch's People on the Highway: “It's better to be going, better to be moving, than clinging to your past”.

Ironically, although he never clung to his past the songs from it were most often part of his repertoire. Stylistically he didn't move far from the soulful, sometimes raw and dark and restless territory he identified right at the start.

He died on October 5, 2011 at age 67.

Neil Young said ,“He was a hero of mine and one of my great influences. Bert was one of the all time great acoustic guitarists and singer-songwriters”.

Johnny Marr offered that, “He completely reinvented guitar playing and set a standard that is still unequalled today. Without Bert Jansch, rock music as it developed in the Sixties and Seventies would have been very different”.

And, of course folk and folk-blues also.

And that is why we need to talk about Bert Jansch.

Elsewhere is indebted to Colin Harper's excellent book Dazzling Stranger; Bert Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival (Bloomsbury)

For more on Bert Jansch at Elsewhere go here. For the sad tale of another character from the early British folk period, Jackson C. Frank go here.

For other articles in the series of strange or interesting characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

Rosco - May 27, 2016

Herein lies the reason every amateur (or professional) musicologist should flock to the digital pages of Elsewhere. Knowledge, research, tasty conjunctive prose with a journalistic nose. This together with the immediacy of Spotify creates a marvelous learning environment for the enquiring mind... and plays merry hell with vocational responsibilities. GRAHAM REPLIES: That's very generous of you, and sorry to keep you from your work. But not really.

Savepost a comment