Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Hawaiian Lullaby

Of all the many hundreds of musical styles across the planet, only one has managed to embed itself in popular, post-Fifties music which exists along the Western axis of London-New York-America's West Coast: reggae.

Yes, there are belated flickers and influences (if not downright copying) of Fela Anikulapo Kuti's Afrobeat and some aspects of Sahara blues and Indian music out there. But those styles haven't become part of the pop, rock and hip-hop musical substructure like reggae.

It really has been the only “world music” to make an impact on popular culture.

But it wasn't the first.

Half a century and more before reggae of the Seventies, there was another ubiquitous musical style which got a foothold in many parts of the world. It also came from a balmy island culture: Hawaiian music.

Given its proximity, the continental US was the first to fall for Hawaiian music’s distinctive sound. In the late 19th century sheet music of Hawaiian songs was being published in San Francisco (the Royal Hawaiian Band played in the city in 1883) and Boston. Hawaiian troubadours took to the road with ukulele and steel guitars and hula dancers.

What gave real impetus was the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915 in San Francisco which ran for seven months.

“What appealed to the American musical public was a combination of ingredients, “ says Hawaiian Music and Musicians (edited by George S Kanahele). “The exotic and romantic imagery of Hawaii; the sight of native hula dancers and musicians, as well as the fluid sounds of the steel guitar, the ‘high-pitched’ ukulele, and the new hapa haole [half white] melodies.

“The impact was greatest on Tin Pan Alley from about 1915 to 1925 during which time American composers cranked out hundreds of commercially lucrative ‘pseudo-Hawaiian’ song: Yacka Hula Hickey Dula, Down in Waikiki, Honolulu Moon and many others . . .”

Research shows a Hawaiian troupe touring in Canada in 1910, some seven years after William Miles began teaching steel guitar in Winnipeg.

The play Bird of Paradise, set in Hawaii and with relevant music, opened on Broadway in January 1912 and went on tour across the US and into Canada. After tours by other Hawaiians, it is said most Canadians in larger cities had encountered Hawaiian music by 1920 and there was a substantial audience for it.

There was some kind of spin-off show from Bird of Paradise which went to Europe in 1913, and a litigant took the production to court alleging it had been stolen from her earlier play In Hawaii.

Other less likely places which fell for the sound of Hawaiian music were Japan, England (Edison cylinders of Hawaiian music in the first decade of the 20th century), India (in the Thirties, largely through popular movies), Indonesia (Ernest Kaai’s Royal Hawaiian Troubadours playing in Jakarta in 1919) . . .

In Japan, Hawaiian music came to prominence after the 1923 World’s Fair in Yokohama when a troupe performed and six years later the Moana Glee Club was founded.

And of course, New Zealand where Bill Sevesi and Stan Wolfgramm were popular entertainers from the Fifties onward for almost two decades, playing venues like the Orange Ballroom in Auckland.

The hap haole song Blue Hawaii – not Hawaiian music but it evoked the islands -- was popularised by Bing Crosby (1937) and Elvis Presley in '61 (in his film of the same name, one of three Elvis movies set in Hawaii)

Oddly enough there were

Hawaiian bands and performers in Holland in the Thirties (locals

playing in the style), Finland (steel guitarist Onni Gideon formed

the Oahu Trio in ’41), Sweden (steel guitarist Yngve Stoor from ’36

onwards) . . .

Oddly enough there were

Hawaiian bands and performers in Holland in the Thirties (locals

playing in the style), Finland (steel guitarist Onni Gideon formed

the Oahu Trio in ’41), Sweden (steel guitarist Yngve Stoor from ’36

onwards) . . .

Elsewhere has previously noted faux-Hawaiians like the Waikikis from Brussels, a bunch of revolving door studio musicians who appeared in our pages playing Lennon-McCartney songs in a Hawaiian style.

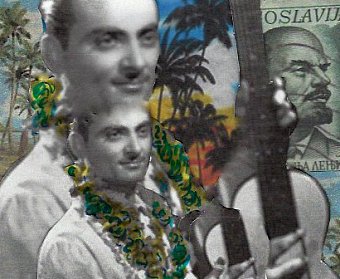

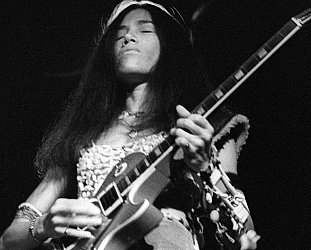

But of all those who learned and played Hawaiian music, none could have been more unexpected than Harry Kalapana who – despite his adopted Hawaiian-sounding name – came from somewhere half a world away from the source: Harry was born in the former Yugoslavia in the early Forties.

It is said that he heard a

Hawaiian record while he was in boarding school and became seduced by

the sound . . . not surprising perhaps given the music evokes the

exotic “Other”.

It is said that he heard a

Hawaiian record while he was in boarding school and became seduced by

the sound . . . not surprising perhaps given the music evokes the

exotic “Other”.

He started playing guitar and was further inspired by seeing Tau Moe play in Belgium. Moe was one of three brothers born in Samoa who had moved to Hawaii when young and who, along with their wives and other Hawaiian musicians, performed Hawaiian music as the Royal Samoan Dancers. Individually or together, or with other groups, they toured through Asia and on the Europe. The Tau Moe Family toured right up into the late Seventies.

Inspired by Moe, Kalapana continued to play and learn, moved the Paris and eventually ended up playing Hawaiian music in Madagascar in the early Fifties.

He returned to Paris and it is estimated that from 1956 to ’67 he recorded at least 200 songs (some under other names, a common practice to spread the exoticism and flood the market with “rivals”).

He retired from music after a car accident n ’76 and details of his later life are unknown.

But there is no shortage of compilation albums of Harry Kalapana in the world. He even turned up on a recent compilation of Pacific music.

A quick look at iTunes

reveals a few albums and 65 songs, he’s on Spotify and of course

his records sometimes turn up in secondhand shops.

A quick look at iTunes

reveals a few albums and 65 songs, he’s on Spotify and of course

his records sometimes turn up in secondhand shops.

Dozens and dozens on vinyl in generic-Hawaiian exotica covers if you can find them.

In style he followed the archetypes but he was also a great advocate and spokesman for Hawaiian music . . . even though he was born in the Balkans and made his career in Madagascar and France.

The mid 20th century craze for Hawaiian music may not have left an enduring legacy in contemporary pop or embedded itself in mainstream music the way reggae has . . . but Hawaiian music happened and had -- still has -- followers, devotees and players all over the world.

And once upon a time, all the way to a boarding school dorm in the post-war Balkans.

And, despite there being so few photographs of the man, that's why we need to talk about Harry Kalapana.

.

You can hear Hawaiian music by Harry Kalapana at Spotify here

.

For other articles in the series of strange, sad or interesting characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

Elsewhere is indebted to Hawaiian Music and Musicians: An Illustrated History edited by George S Kanahele (University Press of Hawaii, 1979) in the preparation of this article.

post a comment