Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Valse Brillante in E Minor

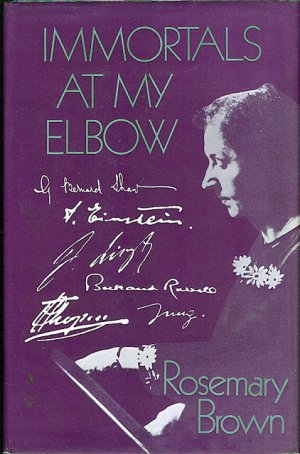

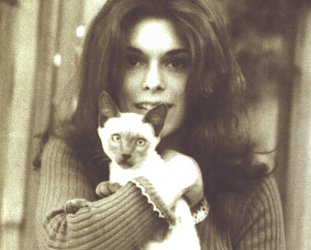

When the English composer and pianist Rosemary Brown died in 2001 at age 85 she took with her an intimate knowledge of the works by some of the greatest classical composers.

This is not uncommon of course. Classical performers and conductors always have a deep and personal connection to the music of those whose compositions they have studied and played.

But Brown's connection to the likes of Chopin, Beethoven, Debussy, JS Bach and others was rather different.

They actually spoke to her from the afterlife and dictated new compositions for her to present.

Or so she said.

She also claimed to have very little musical training, although that proved to be a considerable understatement: she'd grown up in a musical household and had had piano lessons.

But in the late Sixties and Seventies she was quite the sensation when she presented 12 new songs and a huge sonata by Schubert, and previously unknown works by Chopin, Mozart, Liszt and Beethoven amongst others.

“I have more music from

Chopin than any of the others,” she said. “Of course, as his

music is mainly for piano. It does make it easier to dictate his

pieces to me than it is for other composers like Beethoven.”

“I have more music from

Chopin than any of the others,” she said. “Of course, as his

music is mainly for piano. It does make it easier to dictate his

pieces to me than it is for other composers like Beethoven.”

Fair enough, and she knew these people very well.

Brown – who came from a family of psychics – claimed to have been visited by the spirit of Liszt when she was a child, whom she only knew then as figure with flowing hair, not recognising him until a decade later when she saw an image of him.

Things went quiet on the dead-guy front while she married and raised a family but then in '64, three years after the death of her husband and her mother, the classical composers came calling again. Lots of them.

So many that she gave up her job as a school dinner-lady and, with financial assistance from friends and the composer/educator Sir George Trevalyn who established a trust, she was able to work fulltime on keeping up the contacts and compositions.

And by happy circumstance these composers – who were German (Brahms, Beethoven, Bach, Schumann), Austrian (Schubert), Norwegian (Grieg), Polish (Chopin) French (Debussy) and Russian (Rachmaninoff) – all spoke to her in English.

They either guided her hands at the piano or dictated notes. Stravinsky dictated a piece to her a year after his death. It was entitled Revenant.

Psychologists, other

psychics, the media and lay people were very excited by all of this,

but musicologists and those with a more intimate knowledge of the

composers' styles were much less so.

Psychologists, other

psychics, the media and lay people were very excited by all of this,

but musicologists and those with a more intimate knowledge of the

composers' styles were much less so.

“Besides bringing comfort and love, spirits have also stepped in to stop me being made a fool of, “ she wrote in one of her four book.

“Obviously, people like me are fair game for sceptics, and I don't often get interviewed by the media without their trying to catch me out in some way.

“After my first book was published, for instance, there was a great deal of media interest and I was invited here, there and everywhere. I found it pretty nerve-wracking to have to defend myself and my beliefs time and again.

“While I wanted people to know about the music, I felt that I was being treated rather harshly by being put into situations where I had to battle to convince people of my sincerity.”

Many critics and sceptics dismissed these “new” works as mere pastiches or variations on familiar themes. Others were more generous.

Professor Malcolm Troup of the London Guildhall School of Music, acknowledged he couldn't explain Brown's work: “The music is so true to the works we know by the great composers that she would have to be the most fantastic expert on every branch of music to even try and make it up. There are some things we cannot explain. This is one of them.”

Later in life Brown also claimed to have been visited by the spirits of John Lennon (which Elsewhere parodied here), Van Gogh and Shakespeare.

Clearly there was quite a cultural party going on inside Brown's head, and a few psychologists suggested that these were odd aspects of her internal personalities.

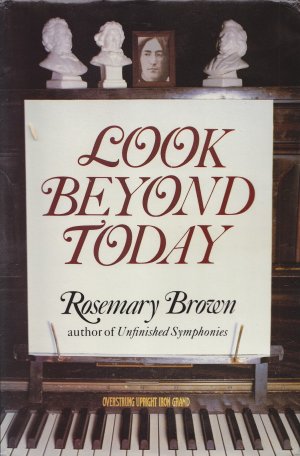

It was just before her fourth book Look Beyond Today in '86 that Lennon, who died in '80, dropped off some new lyrics for three songs – Look Beyond Today, Love is All We Ever Need to Know and Just Turn Away – and told her to pass on the message that young people should stay away from drugs.

"Because I've worked almost exclusively with classical composers in the past, I was most surprised when John Lennon came to see me, comparatively recently, in spring 1985, and visited me quite regularly after that.

"Because I've worked almost exclusively with classical composers in the past, I was most surprised when John Lennon came to see me, comparatively recently, in spring 1985, and visited me quite regularly after that.

"I wondered at first why he had contacted me — I'd been aware of the Beatles, of course, but I can't say I was ever a fan. With two young children to bring up, I was too busy to follow the careers of a pop group.

"Nevertheless, that didn't seem to offend John. I look forward to his visits nowadays, enjoying his Liverpudlian chatter. I believe now he visited me because he knew I was writing another book, and so took that opportunity of getting his most recent thoughts and work before the general public through me.

"He is taller than I always imagined him in this life. I seem to see him as he looked at the height of the Beatles' early success — he looks to be in his late twenties or so, is clean-shaven, fresh-faced, doesn't wear glasses. I can feel great excitement and vitality emanating from him.

"He speaks quietly, tapping his fingers together but not his thumbs. His voice still bears a marked Liverpudlian accent, and when I commented on this once in surprise, he said, 'Oh, that's a part of me.'

"Liverpool went a long way towards shaping John's character, and he still hasn't lost his Liverpudlian traits."

Bill Barry who has been described as a “Lennon expert” dismissed this new work saying, “John never wrote songs as bad as that.”

In her books Brown also revealed the more mundane aspects of her communications from the dead. Chopin had a look at television but didn't rate it, and Liszt got in touch while she was out shopping and was curious about the price of bananas. Sometimes the spirits were simply standing beside her.

While it is easy to

dismiss Rosemary Brown, it need also be noted that many of the works

she transcribed or presented entered the performance repertoire of a

few pianists and were recorded. In '69 – in a BBC television studio

– Liszt dictated a piece entitled Grubelei/Meditation which

impressed a few sceptics. The Liszt expert Humphrey Searle thought

enough of it to say we should be grateful to Brown for making it

available.

While it is easy to

dismiss Rosemary Brown, it need also be noted that many of the works

she transcribed or presented entered the performance repertoire of a

few pianists and were recorded. In '69 – in a BBC television studio

– Liszt dictated a piece entitled Grubelei/Meditation which

impressed a few sceptics. The Liszt expert Humphrey Searle thought

enough of it to say we should be grateful to Brown for making it

available.

She was frequently filmed in the process of receiving music from beyond the grave and right to the end of her life conducted herself with patience towards those who would dismiss her and was unwavering in her belief that these composers were communicating directly with her.

“I am not a trained musician,” she wrote. “ I have no natural talent, no wide musical knowledge, and certainly no desire to perform party-trick pieces like Chopsticks in the style of Rachmaninov.

“The compositions I produce are not skilful pastiches, but entirely new works which bear all the characteristic style of their composers while containing no more than the odd bar or two echoed from a previous work.

“I was understandably worried about this proposed ordeal but Liszt appeared the night before and tried to put my mind at rest. 'Get in first,' he said. 'Tell them you know about people who can produce music in the style of a certain composer, but they are trained musicians, whereas you are not.' “

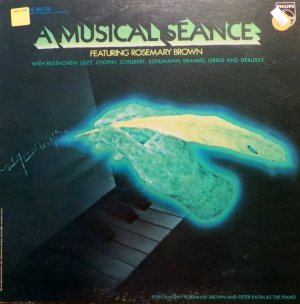

Rosemary Brown's album A Musical Sceance is available on Spotify and iTunes. It is all classical, no Lennon songs.

.

For other articles in the series of strange or interesting characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment