Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Love Epidemic, by the Trammps (DJ Reverend P edit)

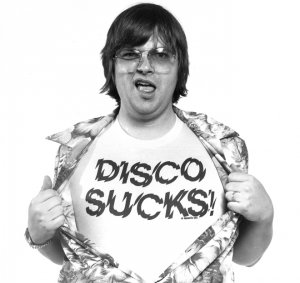

It’s both easy and hard to explain the rise of the Disco Sucks movement at the end of the Seventies.

In some parts of the world the zenith of disco coincided with the

emergence of punk, and two more diametrically opposed styles could hardly be

imagined.

For the most part disco was chic, sleek, well-dressed, celebratory and

precision crafted music. Punk was . . . pretty much the exact opposite.

In broad terms one was black and the other white; one was gay and the

other either heterosexual or asexual; one was poised and beat-driven and the

other pure inchoate energy; one was colourful and the other monochrome; one was

apolitical and the other vehemently full of social comment . . .

Only the parallel rise of reggae as a roots music with consciousness (of

history and culture) alongside emotionally distant and machine-made synth-pop

in the Eighties could compare with the distance between disco and punk.

But there was no Reggae Sucks or Synth-Pop Sucks movements, backlash and

aggression.

So, obviously, there was something about disco which got right under the

skin of a huge section of young, music-loving society.

That it outsold punk by leagues perhaps had something to do with it:

punks could therefore make a greater claim to their marginalization which only

confirmed for them the truth of their anti-capitalist, anti-establishment

position. Nothing becomes a movement like its own sense of martyrdom coupled

with righteousness.

But not everyone was a punk in the late Seventies, and certainly not in

the US where it wasn’t until New Wave – pop music clipped around the ear by

punk and told to sharpen up – that a different, major rock style swept through.

In the US where the Disco Sucks movement took hold the mainstream music

was still stadium rock with an overlay of hard rock. The music press was

dominated by magazines like Creem and Rolling Stone, and they were staffed by

white, heterosexual males who had grown up on guitar bands.

Disco – which emerged out of black, gay clubs in Chicago and New York, and

didn’t place the phallic guitar at its centre – was anathema to these music

writers and their audience.

More charitably, they simply didn’t get it.

More charitably, they simply didn’t get it.

But a few not only didn’t, they didn’t want to and wanted to make sure

others didn’t either.

The figurehead of the Disco Sucks movement in the US was a radio DJ on

Chicago’s WLUP-FM, an all-rock format: Steve Dahl.

According to Dave Haslam’s Adventures on the Wheels of Steel; The Rise

of the Superstar DJ (Fourth Estate, 2001), Dahl had previously “resigned from

another radio station in the city when they switched to playing disco, and had

a thing for scratching the needle across the grooves and then smashing up disco

records live on air”.

The irony wouldn’t have occurred to Dahl that this was exactly what reactionary radio DJs did in the Fifties when rock’n’roll emerged.

Dahl didn’t confine his anti-disco activities to just angry on-air

antics, he was behind the disruption at a Village People concert where

marshmallows (!) with “Disco Sucks” written on them were hurled at the band.

Dahl didn’t confine his anti-disco activities to just angry on-air

antics, he was behind the disruption at a Village People concert where

marshmallows (!) with “Disco Sucks” written on them were hurled at the band.

Dahl’s major moment however came when he organized the notorious “Disco Demolition Rally” at a baseball encounter at Chicago’s Cominskey Park in July ’79.

On the day, there were to be two games between the local White Sox and the Detroit

Tigers and fans got in cheap if they carried a disco record with them.

Between the two games about 10,000 records were collected and tossed in

a container on the field . . . and blown up.

As Ringo Starr once observed about Beatle records being destroyed after

Lennon’s famous “more popular than Jesus” comment: “There were bonfires of them

– what was okay for us because later they rebought them!”

But the event at Cominskey Park attended by 70,000 didn’t stop with

that, a full-blown pitch invasion ensued where fans burned records, chanted “disco

sucks”, the field and stadium were damaged, and the invasion prevented the

second game being played. It made international news.

But the event at Cominskey Park attended by 70,000 didn’t stop with

that, a full-blown pitch invasion ensued where fans burned records, chanted “disco

sucks”, the field and stadium were damaged, and the invasion prevented the

second game being played. It made international news.

Dahl wasn’t alone in his dislike if not hatred of disco: record producer

Richard Perry – who later did albums for Donna Summer – said in ’76, “the disco sound is a

sound I abhor. It’s one monotonous driving beat. It’s as if the human race is a

bunch of cattle that’s got to be given a beat to move to”.

Again, preachers in the rock’n’roll era railed against the evil of “the

beat, the beat”.

At the time of Dahl’s event, disco dominated the charts, the Grammys and

had gone global. As the song said, “You can’t stop the music”.

Saturday Night Fever was the film of its era as much as the Beatles’ A

Hard Day’s Night and Blackboard Jungle had been emblematic of theirs.

The Beach Boys’ Here Comes the Night from ’67 was extended into a disco

dancefloor single.

But Dahl – who pronounced the word “disco” with a deliberate lisp when

on air – wasn’t alone in reviling disco . . . but that lisp was telling.

At core, there was in rock culture -- which once prided itself on its openness

and colour-blindness – a nasty streak of racism and homophobia.

That racism was encapsulated in ’79, as Haslam notes, when the pages of

The Young Nationalist – a paper from the extreme right-wing British Nationalist

Party and aimed at young people – said, “Disco and its melting pot

pseudo-philosophy must be fought or Britain’s streets will be full of

black-worshipping soul boys”.

That racism was encapsulated in ’79, as Haslam notes, when the pages of

The Young Nationalist – a paper from the extreme right-wing British Nationalist

Party and aimed at young people – said, “Disco and its melting pot

pseudo-philosophy must be fought or Britain’s streets will be full of

black-worshipping soul boys”.

You’d hate to tell them that that horse has long since bolted.

But even mainstream music writers, years after disco’s heyday, couldn’t get their heads around the phenomenon or quite why so many people enjoyed it.

Haslam again: “The 1989 edition of the Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music

describes disco as ‘a dance fad of the Seventies with a profound and

unfortunate influence on popular music’ and also laments the existence of

anonymous ‘disco hitmakers’ and record producers using ‘drum machines,

synthesisers and other gimmicks at the expense of musical values’.”

And these “values” might be?

That young women liked disco and danceclubs – where they felt safe

amongst gay men – only added to the damnation from white guitar-rock oriented

musicians and artists.

And then – just as happened when rap emerged – the walls eventually came

tumbling down: the Stones and Kiss mixed in disco grooves, civilians everywhere

got the joke of the Village People, early hip-hop turntables riffled through

their parents disco records and cut-out stores to find those great beats . . .

But, as we have noted previously at Elsewhere,

if you look through the books on popular music there will be considerable space

given to punk rock but disco still struggles to be given its due.

Yet its producers were innovative (no one could doubt

the genius of Giorgio Moroder, surely), many of the artists like Donna Summer and Loleata Holloway could really sing soulfully, there were great songwriters at work

(we start alphabetically with the Bee Gees) and, “Like it or not,” as we wrote, “disco was

massive from the mid Seventies. The soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever has sold

in excess of 40 million copies, the only double album to do so.

“That is big .

. . and the movie which spawned it returned 70 times its production cost.

“Yet a disco act

like Gloria Gaynor (who sang the dance classics I Will Survive and Never Can

Say Goodbye, and whose debut album was the first to put a disco mix medley on

record) gets less space in the history books than a band like Happy Mondays.”

Fortunately it’s

never too late to discover the shameless pleasure in disco.

post a comment