Graham Reid | | 6 min read

Dominique

When the virginal singer Jeanne Deckers – sometimes Jeannine -- enjoyed a sudden hit in the early Sixties it was clear to anyone outside her circle that her career could only go one of two ways.

The first was that she would struggle to follow it up, her life would become a series of disappointments and she would be only remembered as a one-hit wonder.

The other path was that of the equally chaste Marianne Faithfull who did have a follow up to the Jagger-Richards penned As Tears Go By . . . but then whose life became a series of struggles and disappointments until she came out the other side more than a decade later.

Either way,

Deckers was going to struggle and her personal situation conspired against any

notion of a happy career where one hit would follow the other and she’d travel

the world as a famous pop star.

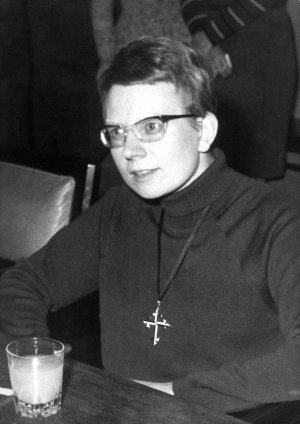

Deckers was

a 23-year old Dominican nun in Belgium when she had a hit with the catchy

Dominique – all in French – which topped the charts in Canada, New Zealand and

the US and went top 10 in half a dozen other countries.

The

question about her short career might not be about what happened to her

afterwards – it was a struggle, there were disappointments and sadness and

eventually real tragedy as we shall see – but how come a nun known as Soeur

Sourire (Sister Smile) within the order would record and release the single in

the first place.

The

question about her short career might not be about what happened to her

afterwards – it was a struggle, there were disappointments and sadness and

eventually real tragedy as we shall see – but how come a nun known as Soeur

Sourire (Sister Smile) within the order would record and release the single in

the first place.

The flowery

liner notes to her album begin, “Once upon a time a young girl stood outside a

music shop in Brussels, looking wistfully at the guitar in the window” so we get

a glimpse of what her record company wanted us to believe.

That young

girl bought the guitar and – in the great tradition of BB King – gave it a

name: Adele.

She and

Adele then went to the Dominican abbey at Fishermont near Waterloo (yes, that

one) and took the name Sister Luc Gabriel.

Back to the

liner notes: “The young novice enthusiastically embraced convent life and this

life gave back warmth and love, direction, purpose”

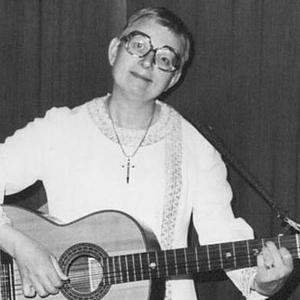

Sister

Smile seemed to enjoy her work and prayer and study, and also the time she had

to write and sing.

On one

occasion, she played to some young girls visiting and “a magic spell held sway”.

“The girls

begged for an encore. Could we have a recording made to take home with us?’

they pleaded. Sister Sourire was astonished, the other nuns were intrigued. Why

not share this gift of song and music?

“With the Reverend Mother’s permission, the decision was made.”

And so it

was that Sister Smile and Adele went to a studio in Brussels and sang to some

people from the Philips company.

And so it

was that Sister Smile and Adele went to a studio in Brussels and sang to some

people from the Philips company.

“The voice

and the music ceased. The studio was hushed. ‘Can we not let the world hear

this voice, so pure and strong,’ the Philips directors asked.”

And so the

song Dominique – about St Dominic, the order’s founder, and his travels and

preaching – was released and became a surprise hit for the 23-year old.

But there

is more of a backstory than this romantic picture presented to the world in the

elaborate booklet within the gatefold-sleeve album cover (which also came with

four prints of her watercolours).

Deckers had

been the daughter of a baker who had tried her hand at art college but suffered

a breakdown over a love affair, and that lead her to the convent gates. It was

at her instigation – to raise money for the order’s mission in Arica – that she

was allowed to record her songs.

She – with a

severe countenance and wire rim glasses -- was also far from Sister Smile, the

name her Mother Superior insisted she adopt rather than her own name.

It didn’t

go unnoticed at the time that the benign figure of St Dominic she painted wasn’t exactly

true either: He was the man who, if he didn't give the world the Spanish Inquisition, was certainly in the vanguard of the persecutions.

And when

the song took off she was very uncomfortable with the attention.

“I

was afraid I would have a breakdown,” she once wrote. “I could not stand being

pestered and importuned by handsome men. I received bouquets from admirers and

some of the notes they sent were too explicit for a girl who lived in a

convent.”

When

some US teen pop magazine gave her an award she was dismissive and horrified: “They

might as well have awarded me a bomb,” she later said.

When

some US teen pop magazine gave her an award she was dismissive and horrified: “They

might as well have awarded me a bomb,” she later said.

And

within the order there was some envy at her success.

So she enrolled at university, fell in love with a

novice Annie Pecher some 11 years her junior and they moved in together.

Scandal

followed, of course.

But worse was to come: All her royalties had gone to the convent but she was thumped with a massive tax bill, and she hadn’t kept receipts or even knew how much she had earned.

The tax collector was relentless.

She

began to rely on those old stand-buy, booze and pills. She tried to resurrect

her singing career but by that time, the late Seventies, no one was interested,

other than the curiosity value of her writing a song in praise of the

contraceptive pill and another entitled Sister Smile is Dead.

She even did a bloodless disco version of Dominique in '83.

Dominique (Disco Version)

Outside of that she and Pecher tried to open a home for autistic children but it failed after a couple of years for want of money.

And

for someone who had once escaped into a world free of such considerations, and

who earned a lot but never saw much of it, money worries plagued her final

years.

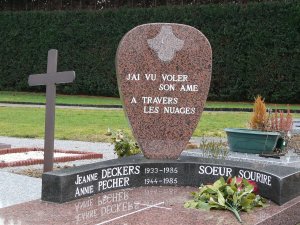

They left a

note which read, "We have reached the end, spiritually

and financially and now we go to God”.

They

said the financial pressures had been too much.

In

a final request the note asked for discretion in the coverage of their deaths.

That was never going to happen: the

arc was too easy to write . . . and she’d been played in a vacuous Sixties

movie by the eternal virgin Debbie Reynolds.

The story

got even more messy after Deckers’ death.

The story

got even more messy after Deckers’ death.

Her manager

and executor Jean Berlier -- who had all her private papers, photographs and

journals -- lent them to a businessman/publisher Luc Maddelein who said he was

intending to write a book.

Berlier

died while he was still in possession of them and, by some accounts, refuses to

relinquish them or make them available to other researchers.

Some

writers such as the American DA Chadwick – who wrote a biography Music From the

Soul: The Singing Nun Story – have been frustrated by the lack of access to the

papers.

Chadwick

incidentally takes issue with those who describe Deckers and her life partner

Annie as being involved sexually. Both, she says, took vows of celibacy and “it

is disrespectful to assume that they broke their vows”.

Chadwick

incidentally takes issue with those who describe Deckers and her life partner

Annie as being involved sexually. Both, she says, took vows of celibacy and “it

is disrespectful to assume that they broke their vows”.

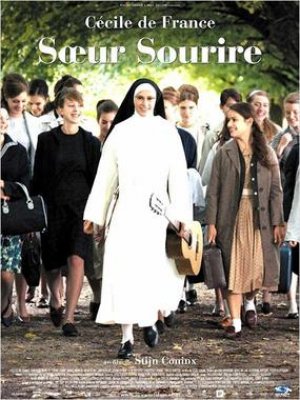

So, the story of the Singing Nun reached well beyond her one hit song.

There was another film made more recently, the 2009 French-language feature Soeur Sourire, which covered the full length of her life.

But with

her private papers unavailable much of what we know may be disputed in a world

of “alternative facts”.

What we do know is that her story was probably never going to end well.

And not even a techno mix of Dominique in '94 could rehabiliate her career.

In fact, you could say with that, it ended even worse . . .

Dominique (Techno Mix)

For other articles in the series of strange or interesting characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment