Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Depending on what angle you look at Hugues Panassie from, the Parisian was either jazz's greatest European advocate and instigator in the Thirties and Forties.

Or he was a divisive and opinionated cuss whose dogmatic writing and dismissal of many artists shoved an unwelcome wedge between styles and musicians.

As with so many purists – Ken Colyer in Britain in the Fifties, some in the neo-conservative movement in the Eighties and Nineties – Panassie knew what the true jazz was . . . and if you weren't playing it then you needed to called out and ostracised.

Maybe that sounds harsh, but Panassie didn't pull his punches.

He was a “New Orleans “man through and through who – from the distance of France where he listened to records lent to him by the equally dogmatic clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow – loved black artists from the South and was dismissive of white musicians.

But he was especially brutal on black artists such as those – and this would of course come to include Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk and others in time – who didn't play in that original New Orleans style.

To his slight credit however he sometimes didn't really see colour . . . but certainly knew what he wanted to hear.

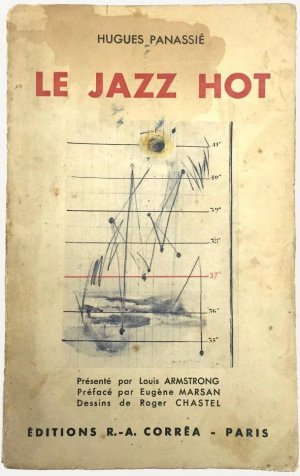

He was a prolific writer (Le Jazz Hot and The Real Jazz being two of his better known titles) and started his own monthly magazine in Paris, then went on to found the various Hot Clubs as well as doing radio shows, producing records and more.

He had the enthusiast's energy and the fervour of a missionary when it came to spreading the word about New Orleans jazz, and sometimes it was at his peril.

When the Nazis took over France and had a bitter hatred of Negro-Jewish music (jazz) a censor came round to check out what he was playing on his radio programme.

According to Mezzrow's jive-talking, self-aggrandising and freewheeling autobiography Really the Blues, “[the censor] was shown a record labeled La Tristesse de St Louis and Hugues explained helpfully that it was a sad song written about poor Louie the Fourteenth, lousy with that old French tradition.

“What that Kultur-hound didn't know was that underneath the phony label was the genuine Victor one, giving Louis Armstrong as the recording artist and stating the real name of the number; St Louis Blues”.

So

you would never doubt Panassie's courage and commitment, but once he

got his teeth into what he considered “real jazz” – of the type

Mezzrow played and also believed in – there was no stopping him.

So

you would never doubt Panassie's courage and commitment, but once he

got his teeth into what he considered “real jazz” – of the type

Mezzrow played and also believed in – there was no stopping him.

He hadn't always been like that and in fact his first forays into jazz writing were fundamentally flawed when he dismissed black artists, but then he came round.

Hard around.

White artists were relegated way down his totem pole, at the top of which was early Louis Armstrong.

And while he railed against white artists there was one he held in high regard: his friend and supporter Mezz Mezzrow, of course.

Perhaps it was the language of the war which shaped his opinions, but he wasn't averse to calling people like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis “traitors” to the cause of jazz and black music, and sometimes advancing what seemed like a revisionist view of jazz as something akin to a cultural project rather than a music.

But from whatever side of the prism you looked at him, no one doubted his passion for the music he loved and believed in.

It was just, as many more recent writers quickly point out, he was often so wrongheaded. In his '83 biograhy of Louis Armstrong, the American James Lincoln Collier cites reviwer Otis Ferguson in the New Republic calling a Panassie book "a standard source of extremely valuable misinformation" and noted that many fell for a flawed cliche about European jazz writers such as Panassie and the Belgian Robert Goffin.

"This viewpoint -- that Europeans understand jazz better than Americans do -- has been enshrined in the sometimes damp grotto of jazz history for so long that it has been accepted, even by Ameircans who ought to know better."

But, as with Mezzrow – who also railed against jazz which wasn't like New Orleans music: “dignified, balanced, deeply harmonious, high-spirited but pervaded all; through with a mysterious calm and placidity” – Hughes Panassie, who died in '74 aged 62, was a man who heard a music he loved and remained vehemently and violently true to it.

Rightly or wrongly.

For other articles in the series of strange or interesting characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment