Graham Reid | | 5 min read

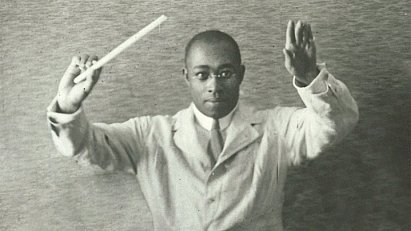

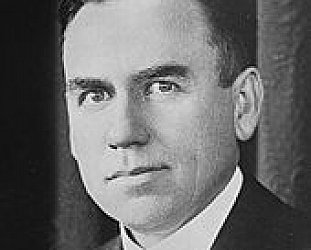

When the 39-year old conductor/composer James Reese Europe was stabbed by one of his drummers, Herbert Wright, and subsequently died, it cut short an already remarkable career and one which seemed poised to go on the greater things.

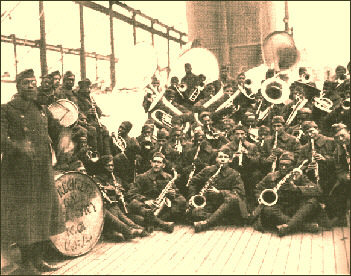

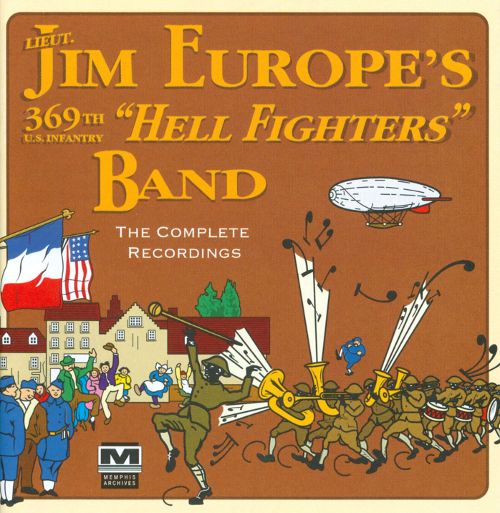

That was in May 1919 and 14 months before he and his black orchestra – the Hellfighters Band – had undertaken a five-week tour of Europe traveling 2000 miles, playing in more than 20 cities and bringing dance music to troops and civilians during the dark days of World War I.

One report said “the band had a reputation among the troops as the jazziest, craziest, best tooting outfit in France” and “the civilian population in Paris and elsewhere praised it to the skies”.

One report said “the band had a reputation among the troops as the jazziest, craziest, best tooting outfit in France” and “the civilian population in Paris and elsewhere praised it to the skies”.

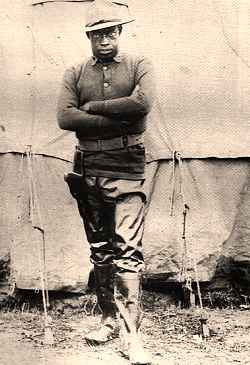

Alabama-born Europe was a star before the war: In 1914 he was behind a Carnegie Hall concert which featured 125 musicians (10 pianos, seven cornets, eight trombones) and when the war started he was given the rank of lieutenant in a black unit dubbed the Harlem Hellfighters and subsequently directed the regimental band, hence the Hellfighters.

When the regiment came back from Europe in February 1919 they marched behind Europe's 90-piece band from Fifth Ave to Lenox Ave in Harlem where they played Here Comes My Daddy Now and the strict columns broke ranks as soldiers found their loved ones.

Europe's death was a tragedy and although being stabbed in the neck with a penknife by the irate Wright seemed slight at the time – he encouraged the band to finish the set at the hall in Boston – he died in hospital later that night.

He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery and, as befitted a man who was at the time the best known black bandleader in the country, there was a huge funeral.

Europe wasn't so much a jazz man but he was an important figure in the dance era – when jazz was a music for dancing more than for study and to listen to. His style was a bridge into the more recognisable (and perhaps by definition) “jazz” style of the following decades.

But Europe was more than just a musician.

Born in Mobile in 1881, he moved with his family to Washington DC when he was 10 and in 1904 – after completing his eduction and some musical training – he headed to New York with the intention of becoming a musical director for black touring companies.

It took a couple of years but after a tour with the “Sho Fly Regiment” he returned to New York in 1909, played in small orchestras and taught piano.

But he also saw the poor conditions black musicians suffered in comparison with their white counterparts. The following year he made his move.

As Phyllis Rose wrote in in Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time, “The one exception to the rule that blacks played for blacks and whites played for whites was in the area of music, and this was thanks largely to the exertions of a single man, James Reese Europe. A managerial genius, Europe had seen that organisation was necessary if black musicians were to make any money from music.

As Phyllis Rose wrote in in Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time, “The one exception to the rule that blacks played for blacks and whites played for whites was in the area of music, and this was thanks largely to the exertions of a single man, James Reese Europe. A managerial genius, Europe had seen that organisation was necessary if black musicians were to make any money from music.

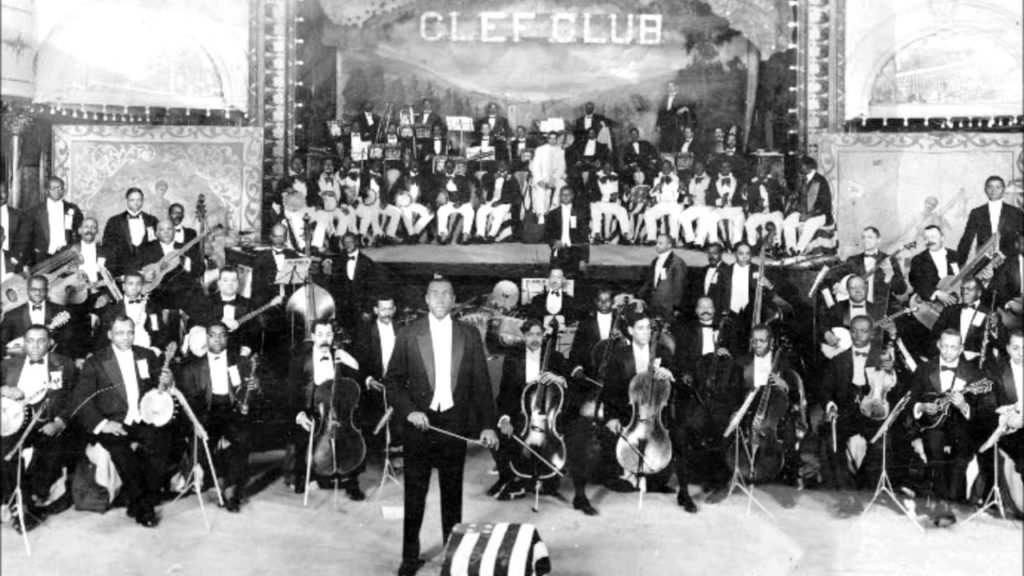

“He gathered many of them into an organisation, part social club and part booking agency, called the Clef Club with headquarters on West Fifty-third St.

“Anyone in New York City who wanted to hire a band with black musicians had to go through the Clef Club which boasted it could supply any size group, from three to 30, at the briefest of notice.”

Europe wasn't the first to try to organise black musicians – four years previous there had been the New Amsterdam Musical Association of New York, but the Clef Club was certainly the most successful.

He was a visionary – Eubie Blake, who called Europe “the Martin Luther King of music”, said that before Europe black musicians had been no better off than wandering minstrels – although in his wish to embrace high standards he excluded ragtime and other popular syncopated styles and erred towards popular music.

He formed an orchestra and had a concert at the Manhattan Casino in 1910 where the group played popular songs of the time, light classical pieces and, oddly enough, a few ragtime tunes to accommodate the audience.

It was a huge success and other concerts followed, one in 1913 pulled almost 400 people.

It was a huge success and other concerts followed, one in 1913 pulled almost 400 people.

Europe insisted on high standards of dress and presentation from the players and turned music into a serious profession for many. He was responsible for the first jazz concert at Carnegie Hall in 1912 (some sources have said 1914 but that is incorrect) with at least 125 instruments (again sources contradict each other).

It was an enormous success – the programme also included religious songs and ragtime alongside each other – and made Europe famous.

Alongside the music however, Europe he had a sense of racial mission and wanted black musicians playing wherever white musicians had been accepted. But he also wanted black music to be accepted as being as valid and European styles: "We colored people have our own music that is part of us. It's the product of our souls; it's been created by the sufferings and miseries of our race."

Europe aimed high and his bands were often large orchestras.

Europe aimed high and his bands were often large orchestras.

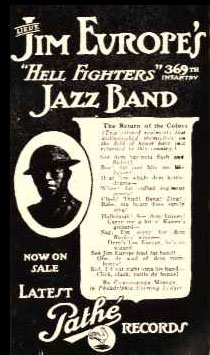

During the war he recorded for Pathe in France and when he returned home his sense of mission was even more refined.

"I have come from France more firmly convinced than ever that Negros should write Negro music. We have our own racial feeling and if we try to copy whites we will make bad copies ... We won France by playing music which was ours and not a pale imitation of others, and if we are to develop in America we must develop along our own lines."

But he didn't live long enough to see that come to full fruition.

Just a few months after that triumphant march through New York he was dead at 39, eulogized by many musicians and mourned by his public.

As the Library of Congress notes: The impact of James Reese Europe on American music cannot be overestimated . . . . he shaped not only the music of his own time, but of future generations as well. His organizational accomplishments . . . prefigured the black-owned, black-run musical organizations that have existed since his time and to this day.”

And yet his name is largely unfamiliar to even jazz historians whose research doesn't take them back into his era and he mostly remains either a footnote or passed over in a few sentences in many books.

And yet his name is largely unfamiliar to even jazz historians whose research doesn't take them back into his era and he mostly remains either a footnote or passed over in a few sentences in many books.

As Albert McCarthy observed in his book Big Band Jazz (1974), “It is impossible to know the direction Europe's musical involvements would have taken, had he lived, but it seems probable that in due course his sharp awareness of what was most in demand would have made him part of the jazz scene.

“In many ways this dignified, somewhat withdrawn man was as far removed from the stereotype of the black entertainer of his period as could be imagined.”

And that is why we need to talk about James Reese Europe.

For other articles in the series of strange, interesting, ignored or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment