Graham Reid | | 4 min read

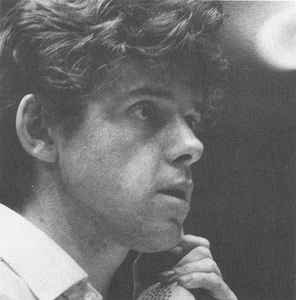

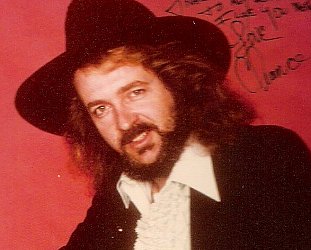

The legendary British folk singer Shirley Collins once said of David Munrow that he was incandescent.

“He had so much energy that you really did feel if you put your finger on him you would get an electric shock.

“I've never met anybody like him for absolute focus, and this energy crackling out of him.”

It was an opinion widely shared.

Christopher Bishop wrote of “his manic energy” and said composer/arranger Munrow “would stay up most of the night preparing parts, then be at the session an hour before it started, putting out the music stands”.

“We had to restrain him from putting out the microphones as well. He would never spare himself during a session, and usually ended up pop-eyed with exhaustion.”

Unfortunately Bishop – Munrow's friend and producer – said that in the obituary published in Gramophone magazine.

The gifted multi-instrumentalist – who brought ancient instruments and forgotten music into the 20thcentury – hanged himself in 1976 at just 33, curtailing a remarkable and productive career which had lasted less than a decade.

The gifted multi-instrumentalist – who brought ancient instruments and forgotten music into the 20thcentury – hanged himself in 1976 at just 33, curtailing a remarkable and productive career which had lasted less than a decade.

In that time however -- from the late Sixties when he was a prime mover behind the Early Music Consort of London (dedicated to playing period instruments and music from as far back as the Middle Ages) -- David John Munrow changed the way people heard and played music from the past.

The son of a dance teacher and PE teacher, Munrow had that rare ability: he could pick up any instrument and quickly learn to play it.

He began on piano and bassoon, became a choral singer and when he was 18 rather than going direct to Cambridge to study English, he took a year off and went to Peru as a teaching assistant at a school in Lima.

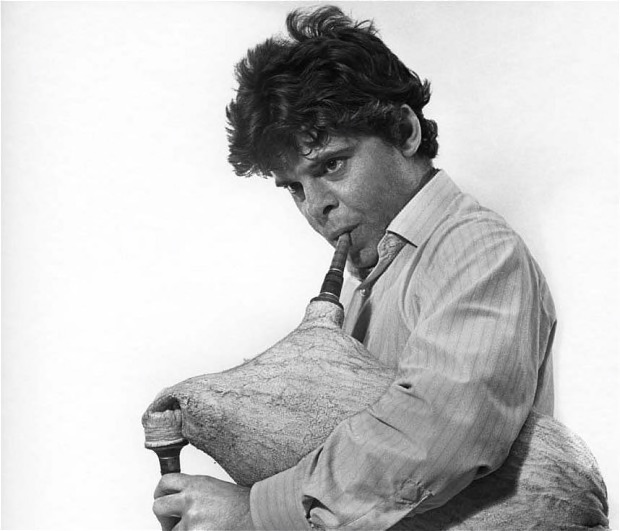

During downtime he traveled extensively in Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Brazil and was seduced by the sound of the pan pipes, flutes and ocarinas played by Andean musicians.

And there his journey into diverse musics took shape. He returned to Britain with a number of indigenous flutes, quite unfamiliar in the early Sixties in those years before Andean musicians appeared on every High Street and marketplace from Edinburgh to Prague.

And there his journey into diverse musics took shape. He returned to Britain with a number of indigenous flutes, quite unfamiliar in the early Sixties in those years before Andean musicians appeared on every High Street and marketplace from Edinburgh to Prague.

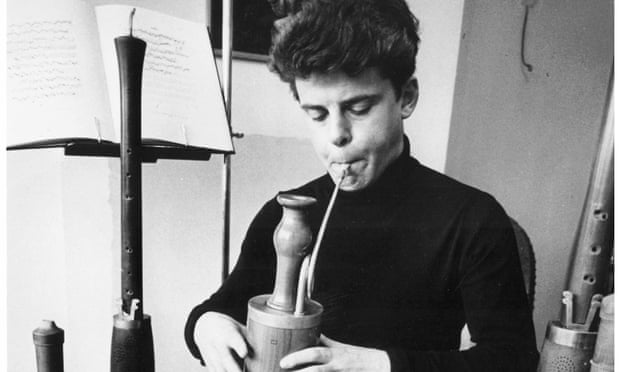

While at Cambridge he spotted a Renaissance-era crumhorn hanging decoratively on the wall of fellow student's room.

He taught himself to play it and then sought out and learned how to coax music out of obscure instruments such as sackbuts, tabors, racketts, shawms . . .

Those he read about but couldn't find in marketplaces and junk shops he commissioned to be made by craftsmen using old illustrations and paintings as their model.

By his late 20s, with an array of instruments at his disposal and an interest in Baroque music, he met composer/instrumentalist Christopher Hogwood and they formed the Early Music Consort of London.

And he joined Musica Reservata, another ensemble dedicated to preserving and playing music which had gone unheard for centuries.

Both these ensembles recorded, Munrow became a lecturer in early music at the University of Leicester, made programmes for television, toured extensively and wrote for films, television and many programmes for radio (music for the BBC serialisation of The Hobbit).

Not long before his death he published Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, a readable book with a double CD set of recordings of the instruments described.

Not long before his death he published Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, a readable book with a double CD set of recordings of the instruments described.

Although he may have seemed the purist, among his film work was music for the John Boorman/Sean Connery fantasy Zardoz, an album with reputable British jazz musicians (Kenny Baker among them) where they played contemporary songs by Lennon-McCartney, Bacharach and others, and the music for Ken Russell's The Devils (in a medieval style).

He was not a populist although believed in taking music to the people, and through his radio and television work became very popular.

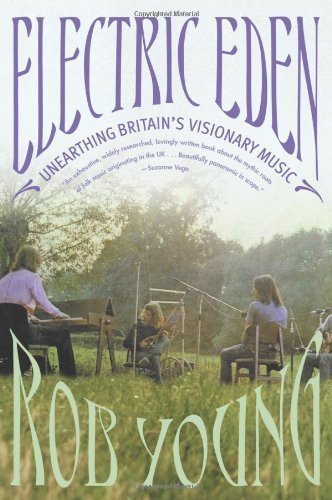

He reinvigorated early music and, as Rob Young notes in his superb study of British music, Electric Eden, Munrow “played a decisive role in the battle to liberate folk music from its conventions in the Sixties”.

He was, in his own way, as influential as Fairport Convention, Pentangle, Steeleye Span and others on the folk-rock journey.

He was described as charming, humorous, effervescent, colourful, a perfectionist . . . and in his obituary Christopher Bishop concluded, “I know of no musician more widely talented than David Munrow, nor anyone whose absence from the musical scene could be more bitterly felt by his audiences, and by his friends”.

Munrow was a believer in identifying the authentic sound of the instruments and the periods he and his ensemble were exploring, whether it be the Crusades, the Gothic era or music of the medieval Netherlands.

His sheer energy and availability pushed him into the foreground of a movement which challenged preconceptions and popularised early music. He was as attached to recordings as the concert stage.

Of his skills on various woodwind instruments – Munrow owned more than 150 and could play them all – the writer for the Guardian, Meirion Bowen, said in '71, “Not even Mick Jagger can have such versatile lips”.

Of his skills on various woodwind instruments – Munrow owned more than 150 and could play them all – the writer for the Guardian, Meirion Bowen, said in '71, “Not even Mick Jagger can have such versatile lips”.

The Munrow catalogue of recordings exceeded 50 albums and it was, in part, that workaholic and perfectionist aspect of his personality which wore him down emotionally.

In '75 he attempted suicide but, in a state of depression after the deaths of his father and father-in-law, he succeeded the following year.

Quite a number of his recordings are still readily available (and on Spotify) and somewhere out there in deep space on the Golden Voyager Record – alongside music by Chuck Berry, Louis Armstrong, Stravinsky, Bach and Mozart – there is a recording of Holborne's 14thcentury Fairie Round for recorder ensemble.

It is by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London.

It is by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London.

And that's why we need to talk about David Munrow.

.

Elsewhere is indebted to Rob Young's wonderful Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music (faber and faber, 2010) in the preparation of this article. Elsewhere has drawn on this in the past and unequivocally recommends this book which is available from amazon here.

.

.

For other articles in the series of strange or different characters in music, WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT . . . go here.

post a comment