Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Yungchen Lhamo: Om Mani Padme Hunge Hung

When this interview appeared in 1999 I was subject to some interesting passive-aggressive communications from people purporting to be sympathisers with the Free Tibet cause who suggested that what I had written about Tibet before the Chinese was "unhelpful".

I pointed out it was however, the truth . . .

In the thorough and informative Rough

Guide to World Music, Tibetan music gets only the briefest mention -

and then only in the context of Nepalese music. Yet that’s hardly

surprising since the politics of that unhappy country, occupied by

China since the late 1950s, has ensured Tibetan traditional music has

been reduced to almost inaudibility.

As with so much Tibetan culture, the

music now exists beyond the geographical borders and is kept alive by

political refugees such as singer Yungchen Lhamo.

But like many Tibetans, Lhamo -- who

fled her homeland at 19 – has become a living emblem of her country

and a spokeswoman for the Tibetan cause and human rights.

She tells of being in the former East

Germany to speak and the hardship there reminded her of her homeland:

“But in Tibet, although the Chinese destroyed the monasteries and

killed the monks, we still have the spiritual side of us.”

With little prompting she unravels the

litany of oppression and torture the Chinese brought with them.

Chinese now outnumber Tibetans six to one in the Tibet Autonomous

Region and other traditionally Tibetan provinces, she says (the

Chinese say there are only 500,000 Chinese settlers in the region)

and torture is a daily occurrence.

Although figures will always be

disputed, estimates by human rights 5 monitors say over a million

Tibetans have been killed since the Chinese occupation and some

150,000 live in exile. As significant is the destruction of

monasteries. There were 6259 of them before the Chinese takeover;

only 1700 are left today. And fewer

than a quarter of the number of monks there 40 years ago remain.

In that context, keeping the culture

alive is a struggle, although 18 months ago Newsweek stated that in

the countryside -- where more than 70 per cent of Tibetans live --

traditions are regaining strength and most of the faithful can

worship unfettered: “Tibetans at home and abroad are almost

universally loyal to their spiritual leader the Dalai Lama.”

But it is, and will continue to be, a

struggle.

Lhamo says that as a child she had

little opportunity to sing “because I didn’t want to sing like a

Chinese.”

“Sometimes we would see a Chinese

movie and when we come out I would sing a little bit of the melody

and my grandmother would say, ‘These Chinese killed your

grandfather and made us slaves, so why act like these people? Why not

learn good things from good people‘?”’

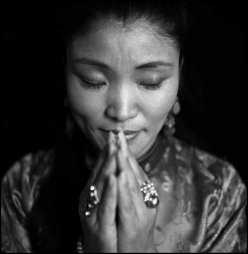

Her grandmother taught her traditional

songs and also said: “If you have talent you should use part of

your spiritual practice to benefit other living beings.”

“At that time I couldn’t understand

what she was talking about -- with people having empty stomachs and

no food, what good does singing do? But people need a spiritual side

and that’s why I sing and tour. I want people to understand whats

really going on inside Tibet and to tell people my experience, not

like reading a book about Tibet.

“And I want to tell people we all

have a spiritual life and we often forget about it because in this

modern world we are so busy for the money and the power. If you have

one side a little bit money and one side a little bit spiritual,

that’s the best way,” she laughs.

As with the Dalai Lama, Lhamo betrays a

cheerful pragmatism. “Some Westerners say Buddhism is emptiness and

don’t want a house or money and want to become monks or nuns. But

when you want to drink a cup of tea you need money.”

For most Westerners Tibet is a curious

hybrid, an almost imaginary land where fantasy and reality become

indistinguishable over geographical and historical distance.

Two years ago the Far Eastern Economic

Review noted that the mystery of this distant land for Americans was

enhanced by the fact that few had ever met a Tibetan and had little

likelihood of ever doing so. Only 300 or so lived in the states of

New York and New Jersey combined.

But far from being the Shangri-La some

imagine, it was a country of monastic feudalism where sometimes

violent factionalism was not unknown.

The Dalai Lama’s controversial 1976

banning of worship of the deity Shugden -- which some observers say

was suppression of shamanistic fundamentalism to present the image of

a unified Tibetan theocracy-- lead to dissent both internal and

within some expatriate communities.

The less-often-asked question therefore

is just how much individual freedom there was before the Chinese

invasion.

“It was not perfect and there were

many faults,” Lhamo concedes but “they never have the Army come

and beat you and take your things or say, 'You did something wrong'

even if you didn't.

“I understand from my grandmother

that we had food even if it was not good. But when I grew up two of

my brothers died because they didn't have any food.

“In old Tibet they didn't have fancy

things but no people died from starvation as I understand it or were

tortured every day over 20 or 30 years. For some people there is no

reason to be punished but if you one sentence like 'Free Tibet' then

you are finished and at least five years you have to be in prison.”

Lhamo speaks of the Tibetan diaspora

and how dispossessed second and third generations of refugee families

keep culture in their hearts and learn from parents and grandparents.

All yearn to return to their homeland, she says.

“You breathe the air inside Tibet and

it has our history. When you touch the earth then you smell Tibet.”

But this raises the question of what

would happen if the Chinese simply walked out of Tibet tomorrow. She

agrees Tibetans who have grown up in the West might have very

different expectations of their country and its future political

direction.

None of this denies the Tibetan

experience of slow genocide at the hands of China’s

one-child-per-family policy, the deliberate influx of Chinese,

destruction of monasteries and shrines and banning of the language.

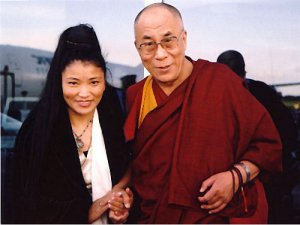

The brutal reality of politics aside,

which Sino-watchers use as a barometer of China’s internal

political climate, Tibet has become fashionably hip and having your

photo taken with the Dalai Lama today seems one better than being

snapped alongside Jack Nicholson.

Last year, two high-profile feature

films about the life of the Dalai Lama reached multiplexes, Martin

Scorsese’s Kundun and the Brad Pitt vehicle Seven Years in Tibet.

Such films, says Lhamo, raise the

profile of her country in the absence of footage on CNN and news

networks.

Dalai boosters include Adam Yuich of

the Beastie Boys; composer Philip Glass, who did the music for

Kundun; Richard Gere; and action-man actor Steven Seagal, who was

hailed as the reincarnated Tulku of the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan

Buddhism a year ago.

Celeb-Buddhists include Tina Turner and

Leonard Cohen, and both REM`s Michael Stipe and Courtney Love have

dropped just enough hints to tantalisingly suggest they might be.

And Buddhism is big business: in the

States computer companies sell screen-savers which draw the

kalachakra (wheel of time); silk prayer scarves and brass censers are

sold alongside baseball caps and t-shirts with pro-Tibet slogans. A

“Free Tibet" bumper-sticker seems the necessary fashion

accessory.

Buddhism’s popularity in America made

the Time cover story in December 1997. And Hollywood’s fascination

with Tibet has got to the point, says China-watcher Orville Schell,

that stars now have “their gardener, their personal trainer and

their lama.”

For the cynical the 90s equivalent of

the 60s Indian guru is now the Tibetan lama.

Lhamo laughs about Tibetan chic. Some

Westerners “want to find happiness and take some Tibetan ideas and

some Buddhism into their hearts. That’s good for them and good for

Tibetan culture -

but they don’t have to drink butter

tea, become monks and wear robes. You don’t have to go on the

mountains to be a Buddhist.”

But she says that despite such

misplaced good intentions, at least Tibet now occupies a place in

Western public consciousness.

Whether that translates into anything

more meaningful for the cause of liberation is another matter. But

the Dalai Lama remains ever-optimistic and patient.

“I think if he doesn’t be

optimistic then we will jump in the river,” giggles Lhamo.

“This situation will be changed

because people not only understand the Tibetan situation but also can

see how bad human rights is in China and the Western world will force

China to change. The Chinese will wake up.

“It will change. Everything always

does.”

post a comment