Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Susan Aglukark: O Siem

It is 1995 and Susan Aglukark is

speculating on how she’d like to see herself in five years; married

certainly (she and her boyfriend have talked about it), a lot of

children, learn to fly, go to law school . . .

Making music doesn't come into it?

"Oops," she laughs and

glances guiltily around the record-company office where she is

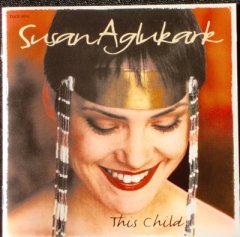

sitting doing promotional work for her album This Child which has

just topped the charts in her homeland Canada.

Forgive her the lapse – she’s been

doing interviews all morning and this conversation has roamed far

from the mundanities of promoting a record.

And she’s come a long way. Few, in

fact, could claim to have come further, either emotionally or

physically.

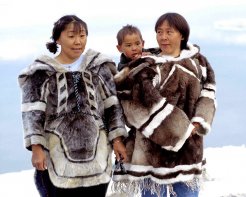

An Inuit singer-songwriter from

Canada’s Northwest Territories, she was in Auckland briefly after a

performance in Melbourne but is easily diverted into discussing the

broader issues pertaining to Inuit peoples.

Aglukark has the credentials. She has

been a linguist with the Canadian Department of Indian and Northern

Affairs, executive assistant the political lobby group Inuit

Tapirisat (Brotherhood) of Canada, spokesperson for the Northwest

Territories Economic Development and Tourism/Arts and Crafts

organisation, and a national spokesperson for the Aboriginal Division

of the National Alcohol and Drug Prevention Programme.

And now, having been one of Canada’s

highest-profile singers for the past four years and over four albums,

she has just been nominated as one of the best new solo artists in

the annual Juno Awards.

“God I hate talking politics,” she

laughs before embarking on a free-ranging philosophical discussion

about the complexities of “aboriginal-whiteman” relations and

observations about young Inuits debilitated by alcoholism, poor

education and lack of a sense of self-worth.

“The people are confused and in a

kind of controlled limbo,” she says of the 35,000 Inuit who have

occupied the Arctic coast and islands of Canada for more than 4000

years.

"Things have changed and change

has caught up on a social level. There are a lot of problems, but not

so much the people haven’t been able to negotiate a land-claims

deal. But we are now in a situation where we have to catch up with

the rest of the world.

“There is a drive for

self-determination and always has been, but there is no animosity

between the white man and the Inuit peop1e.”

The key problem, as Aglukark sees it,

is in the way change has been brought to Inuits who largely live in

remote, small communities such as Arviat (population 1300) where she

grew up.

“If people would listen, especially

in the white man’s world, they would understand that Inuit people

do accept change, because it’s inevitable. The problem in our way

of thinking is that the concept of choice is a very scary thing. In

the last 50 years the people have learned to depend on the Government

because it has taken choice away from them.”

Aglukark notes that young people who

have grown up with television (despite widespread Eskimos-in-igloos

cliches) are open to education. Her own experience is typical.

After going through local primary

schools students have to leave for one of two large boarding schools

and encounter the particular pressures that being away from home can

bring.

Alcohol and drugs are prevalent, she

says. Students tend to drop out.

She did so herself, and drifted for two

years before returning to school.

Many young people, she says, are

victims of abuse, and suicide is common.

“But I'm very optimistic about our

future. I'm a victim of abuse myself, but all my friends are victims

of one form of abuse or other and if that many can survive then I

have to be optimistic."

Aglukark is aware that initially people

within the music business are curious about her because they say,

“Oh, there’s an Eskimo in the industry. . .”

It also makes for some nervousness:

“They wonder what I'll sound like."

But she couldn't have made her light

folk-pop album with aboriginal musicians; there isn’t the

experience in assimilating traditional chants with guitars and

synthesisers."

“Our people don’t have the depth of

experience as creators of this particular music. We have heavy metal

and country bands but it’s difficult for aboriginal people to

understand the advantages of having the two worlds work together in

the entertainment field.

“I think we’re slowly moving away

from that. I’ve written the song This Child as a traditional chant

but it also has different sounds that create a visual sense. I can

sing my chant with the music behind it but my grandparents couldn’t

imagine the sound that backs it. It's beyond their understanding.”

Not unexpectedly, Aglukark sees the

music industry from her own particular perspective; she writes her

songs in the hope they will bridge the generations and be life

affirming, and she discusses with elders the protocol of using

traditional chants within popular culture . . . and donates a

percentage of royalties to various communities.

Aglukark's album The Child sold

triple platinum in Canada, five years after this interview she had a

young son. In 2005 she was named an Officer of the Order of Canada.

post a comment