Graham Reid | | 4 min read

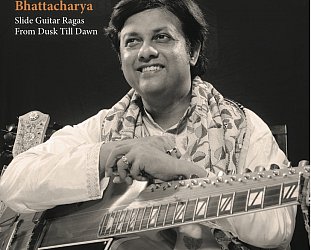

In many ways, the Indian musician

Rajendra Prasanna is an emblem of his country's classical tradition.

As with so many Indian musicians, he grew up in the gurukal system

where he was one of a long lineage who had been taught by their

musician father who would pass on the knowledge acquired from the

previous generation.

Prasanna's father and grandfather were

both musicians, but in some way Prasanna also broke with tradition.

He is one of the rare musicians who plays both shehnai and flute,

learning the former from his father and the latter from his

grandfather who was a legendary innovator and influence in classical

Indian flute.

And the gift gets passed on again:

Rajendra Prasanna's son Rishab is also a flute player an a member of

the small touring group which is bringing the spirit of Indian

classical music to the Taranaki Womad and Auckland Festival (dates below).

“Yes, the music comes down from many

generations and continues through an unbroken chain,” says Rishab

who speaks for his father who has politely said his English is not so

strong before passing the phone over.

Rajendra Prasanna was born in 1956 and

made his first concert appearance before he was in his teens, which

placed him directly in that period when Indian music – through the

passion of George Harrison and the profile of Ravi Shankar – was

gaining international attention.

“It was the shehnai that my father

first learned to play,” says Rishab. “My grandfather introduced

flute into my family and then he made many disciples in India and you

will see that the way the flute is played in India today is because

of the contribution of my grandfather.

“It was the shehnai that my father

first learned to play,” says Rishab. “My grandfather introduced

flute into my family and then he made many disciples in India and you

will see that the way the flute is played in India today is because

of the contribution of my grandfather.

“My father went to Calcutta to a

music conference when he was 12 and that was where he first played in

public.”

Yet for someone so grounded in the long

tradition, the music around him was changing rapidly. Ravi Shankar

has often complained that the music was misunderstood by many in the

West, notably hippies who thought of it as stoner music, but also

inside India where many musicians changed their style to cater for

the growing international audience. Long ragas became truncated to

fit onto LP record, some even edited down to just the fast passages

for singles in the hope of getting radio play. And many musicians

chased the money not the art.

“Because of the contribution of

Pandit Ravi Shankar in the Sixties and Seventies our music became so

popular and many other artists came to understand Indian music. But

my father is very clear about how the music changed and he did not

like that.

“In India we are having many

conferences about that and the questions are, “Who is the real

artist? Who is performing for art and who just for business?” Now

some people want publicity and to attract the public and this is a

different form and not a true art.

“We don't have an intention for

business and publicity, keeping the true art intact is very much away

from these intentions. An artist is complete when he is doing it

fully from himself and feeling that his art is giving him full

satisfaction, rather than if the main aim is to have money and a

business and popularity.

“So this has all been changing and

you see many big Indian artists coming to different countries. But

for us it is important to just present it they way you would in

India, with your soul in it.

“My father is also thinking like

that, that wherever you go you should play your true art rather than

focus on other things. If you focus on your art then only ultimately

it will attract a true audience, if it gives you satisfaction it will

give them true satisfaction.”

Rajendra Prasanna has taken his art to

some impressive stages – he has accompanied Ravi Shankar, including

at the 2002 Royal Albert Hall in the Concert for George – but has

also created soundtracks for Indian films, although Rishab is quick

to note, “not for Bollywood”.

“He didn't work for Bollywood but

worked with many folk music tunes from different parts of India for

smaller films. Rather than make a career in Bollywood he was more

keen to enrich the authentic folk music.”

“He didn't work for Bollywood but

worked with many folk music tunes from different parts of India for

smaller films. Rather than make a career in Bollywood he was more

keen to enrich the authentic folk music.”

Rishab says when the group – with

Vikas Babu on shehnai and Shub Maharaj on tabla – play in New

Zealand and Australia in the coming months they will reach back into

that long tradition and play in the manner of classical raga where

the music develops slowly.

“We play a little alap and this is a

slow improvisation, and then after that it is slowly increasing the

tempo and at the last it is going very fast. This is a principle of

classical music, the little increasing slowly affects the human

emotions in a good way, rather than if you just do something very

fast and then something very slow. It is a complete balance, just

like we can not get shocking news and happy news one after another.

“So we do things slowly slowly and it

becomes a little increase in an ascending way.

“I have to say, we are very excited

to come, it will be our first time in Australia and New Zealand and

we hope to play very well for you all.

“We've heard wonderful stories of Womad and the Auckland Festival, so coming to those is a great honour.”

Rajendra Prasanna and group play the Taranaki Womad March 18-20, 2011 and one concert only in the Auckland Festival on Tuesday March 15 in the Auckland Town Hall Concert Chamber.

post a comment