Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Asheghi Doroughe: Hamid Shabkhiz

In Elvis Presley's trophy room at Graceland in Memphis -- more a trophy annex, with gold discs, costumes, awards, police badges and posters -- there is, framed on the wall, a dramatic headline from a Nashville newspaper and a story sourced from Tehran.

The headline reads "Rock'n'Roll Banned, Hate Elvis Drive Launched by Iran to Save Its Youth". The article is dated August 12, 1957.

The article said rock'n'roll had been banned in Iran because the regime considered a threat: " 'This new canker can very easily destroy the roots of our 6000 years' civilisation,' police said before launching a 'Hate Elvis' campaign'."

Well, it's a pretty fragile civilisation that can be undermined by Blue Suede Shoes . . . but, we must remind ourselves, there was also an extreme reaction by some radio people and parents in Elvis' homeland.

Under the modernisation period of the Shah however, things got a little more liberal (if we may use that word about a country with political prisoners) and during the Sixties and Seventies there was a flourishing pop scene, and people with money to support it.

And rather belatedly they had their own "Afghan Elvis", the hard drinking Ahmad Zahir.

Iran has always had an unusual relationship with Western music. When the Ayatollah Khomeni returned triumphant in 1979 after the Islamic revolution threw out the Shah, his clerics banned all Western music because it was a threat to Islamic state. When a European reporter asked Khomeni if he included Beethoven and Bach in that ban, his reply was chilling and telling: "I don't know those names."

There is pop, rock and hip-hop music in Iran today (not of the Bieber/Lady Gaga kind, of course, but see here) but in the long view -- and from a Western perspective which may, or may not, be relevant -- the later period of the Shah's regime starts to look like a brief golden age.

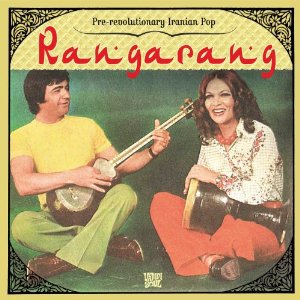

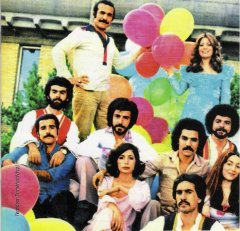

This beautifully presented double album -- with evocative promo photos of the artists from the period -- collects 28 diverse tracks by some of the most famous musicians of that brief flowering, many of whom came to a more tragic end than most of their drug-addled contemporaries in the US or UK.

The potted biographies in the liner notes contain heart-stopping lines like these; "Many Iranians believe that his stabbing and beheading was a death commissioned by the Islamic regime" (Fereidoon Farrokhzad); "She was subsequently imprisoned and then silenced for 21 years before she finally escaped" (Googoosh); "In the 70s a deranged fan sprayed him with a caustic substance and he suffered traumatic burns" (Dariush); and "the Taliban loathed him and desecrated his grave in 1996 . . . he was assassinated on the day of his 33rd birthday, June 14, 1979" (Ahmad Zahir).

And that is just a sampling.

And that is just a sampling.

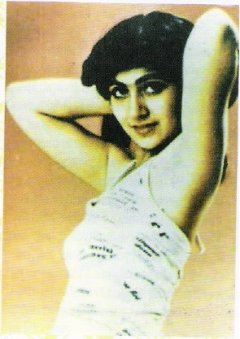

Then there are the more familiar or prosaic footnotes: "Died in exile at the age of 47, unhappy and alone, a diabetic with a history of drug and alcohol abuse" (Hayedeh); "Today she relies on plastic surgery to maintain an illusion of youthfulness" (Leila Forouhar pictured right, in the Seventies) and "Today she is rumoured to have her own dental clinic near London" (Neli).

When the revolution arrived, a long list of musicians had been drawn up and those on it were called before a revolutionary court. It was . . . suggested? . . . they sign the declaration saying they would no longer perform.

Many didn't stick around to either accept or decline, some were out of the country and didn't return (the glamorous, beehive-sporting Shohreh), and a few stayed. Among those who did were Kourosh Yaghmaei who took to writing children's stories, and the beautiful Giti who turned to writing film scores. But while she was seeking cancer treatment in Germany she learned of her husband's affair with Googoosh so she abandoned the treatment and returned home to die.

Iranian pop seems a cavalcade of bad endings.

Many who fled when the revolution came never performed again.

These are all remarkable stories and while much of what is across these two impressive discs won't sound familiar if your definition of pop is determined by the Beatles, Madonna or Justin Bieber, there is some exceptional music on display.

Mehrpouya -- who studied sitar with Ravi Shankar -- offers slinky lounge jazz and a hint of soul-funk on Dokhtare Shab; Neli and Leila Forouhar deliver seductive and slightly dramatic pop (the latter with chipping wah-wah guitars and rippling funk); and that man-stealin' Googoosh sounds every bit the temptress on the quietly unveiling Age Bemooni (If You Stay) and hypnotic Age Mishod Che Mishod.

There is some straight-ahead pop here (Afshin Moghaddam who was killed in a car accident after just one album doesn't stray too far from Then He Kissed Me in places on the orchestrated Gharibooneh); Shohreh brings a wistful and melancholy tone to her deceptively dark pop ballad Omadi; and Beti's memorable Bikasi has her polished vocals offset by hints of surf rock guitar and organ.

There is some straight-ahead pop here (Afshin Moghaddam who was killed in a car accident after just one album doesn't stray too far from Then He Kissed Me in places on the orchestrated Gharibooneh); Shohreh brings a wistful and melancholy tone to her deceptively dark pop ballad Omadi; and Beti's memorable Bikasi has her polished vocals offset by hints of surf rock guitar and organ.

Elsewhere, Habib from Azerbaijan has a deeply soulful and quavering delivery on Gheseye Rooze Siah (Story of a Dark Day); and Leila Forouhar sounds like a powerful pop princess on her horn-enhanced slice of Persian pop-rock with a Latin flourish on Moama, and takes you to an urgently dramatic nightclub on the stunning Hamparvaz.

The "Afghan Elvis" (Ahmad Zahir) sounds nothing like the King at all but has more of a raga-rock sound with tabla and sitar.

Sometimes this music approaches the intersection of world music and rock: The exotic Pooran on the trippy Shahre Paiz with its cannoning drums and weird synth lines; the classically trained, heavily moustached, prog-rocking Kourosh Yaghmaei on the seven minute Khaar (more from him please); and Dariush's politicised Daad Az in Del.

This is a considerable amount of almost forgotten pop, much of it from people who literally suffered for their art. It is also perhaps more Iranian pop than most have heard in their lives.

It is ear-opening, often exciting, certainly exotic and always different.

And none of it sounds like the kind of music which could make the Iranian revolutionary regime of the late Seventies quake and loathe.

If your idea of truth is determined by a literal reading of the Qu'ran, Sharia law and the fear of another "canker", then maybe the guitar funk, wild oud and swirling strings on Ashegh Doroughe by Hamid Shabkiz would make the walls of your citadel shake.

Like the sound of this? Then check out The Rough Guide to Planet Rock, and this. Oh, and this and this.

post a comment